Medieval Padlock Hints at Prosperity of Scotland’s Pictish Farmers

Archaeologists uncovered a thriving farming community whose members wanted to keep their valuables safe

:focal(400x300:401x301)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/07/18078726-dfd8-4ba7-9909-ea9c75c49ed8/download_1.jpg)

Forget cybersecurity. Back in the good old days, plain padlocks were enough to keep a person’s treasures safe—and even after more than a millennium underground, some of these handy artifacts still hold their fair share of secrets under lock and key.

Researchers excavating the archaeological site of Lair in Glenshee, Scotland, have uncovered two medieval padlocks likely used by Pictish locals between the 6th and 11th centuries, reports Alison Campsie for the Scotsman.

Classified by the team as “security equipment” in a recent Archaeopress monograph, the locks probably had a benign purpose, protecting the contents of chests or valuables behind doors. Then again, maybe not: As the researchers write in the paper, “Use to secure animals or people is also possible.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/26/f2261340-309c-458b-a121-ce10e6bf9be6/padlock_schematic.jpg)

Nestled in Scotland’s uplands, Lair was once thought to house the remains of low-status Picts—a group of Celtic-speaking people who first appeared during the Late British Iron Age—struggling to make ends meet on the fringes of true civilization. But the findings of the research team, led by Perth and Kinross Heritage Trust Director David Strachan, reveal that the long-gone community at Lair was actually a permanent prosperous settlement, bustling with successful farmers who thrived on livestock and grain crops for almost 500 years.

“What we have got here is a picture of the everyday, of the upland farmers and how they lived,” Strachan tells Campsie. “We are beginning to get a new picture of the Picts as a stratified society.”

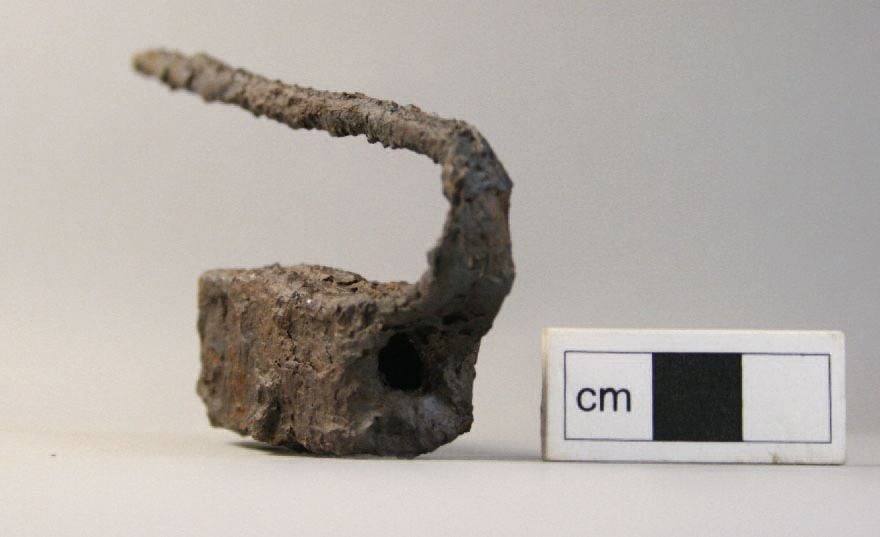

At the very least, the community had enough wealth and class hierarchy to garner some of its members valuables—and instill a healthy suspicion of thievery, says Strachan. That explains the two partial barb-spring padlocks unearthed from the site. When whole, the pair would have each consisted of three components: a case, a U-shaped bolt secured into the case with barbed springs, and a key that would have unlocked the bolt when inserted into the case, according to a statement.

Barb-spring padlocks first came into use in Britain during the Iron Age, sticking around for centuries before falling out of fashion sometime during the 16th century. Despite their origins in the region, though, the locks themselves weren’t always ironclad: One of the two recovered from Lair survived only as a broken bolt.

What exactly the lock was protecting (or restraining) remains a mystery. But several other artifacts collected from the site, including an engraved spinning whorl and a rare green glass bead, hint at the objects the Picts once cherished—and that still hold value for humans today.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)