Lavishly Illustrated Medieval Playing Cards Flouted the Church and Law

Secular and religious officials alike frowned on card playing in Europe’s Middle Ages

Much changes over the centuries—customs, costumes and food spring to mind. Games from centuries past have also evolved; though intriguing, most of the time, ancient games prove unplayable if you don't know their rules. This is not the case with card games, however. While the painted images on early cards might look different, the game itself is familiar, as an exhibition at the Cloisters in New York, shows.

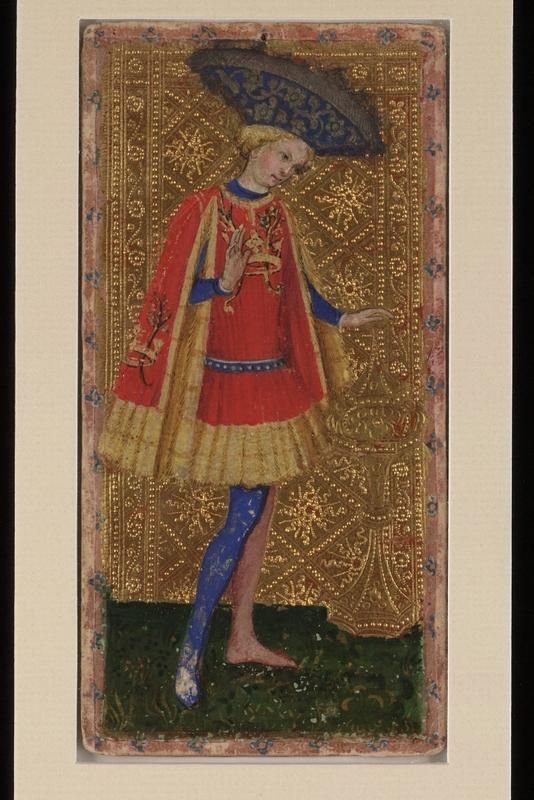

"The World in Play: Luxury Cards, 1430-1540," which is on view until April 17, features carefully crafted cards from the only decks that have survived from the late Middle Ages.

"To be good at cards requires more skill than dice but less than chess, both of which were well established by the 14th century when card-playing came to Europe (from Egypt perhaps, or the Middle East)," the Economist's "Prospero" blog reports. People from all classes would play cards, though the ones on exhibit at the Cloisters were clearly intended for the rich and wouldn't have been subjected to the roughness a deck meant for actual use would have experienced.

"Nobles and rich merchants kept these cards in decorated, fabric-lined boxes. Only occasionally were they taken out to gaze upon and dream, laugh or ponder," the Economist points out.

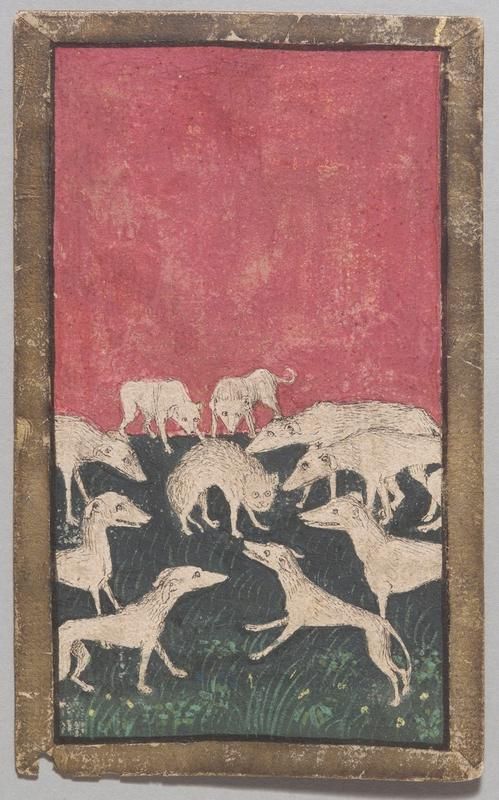

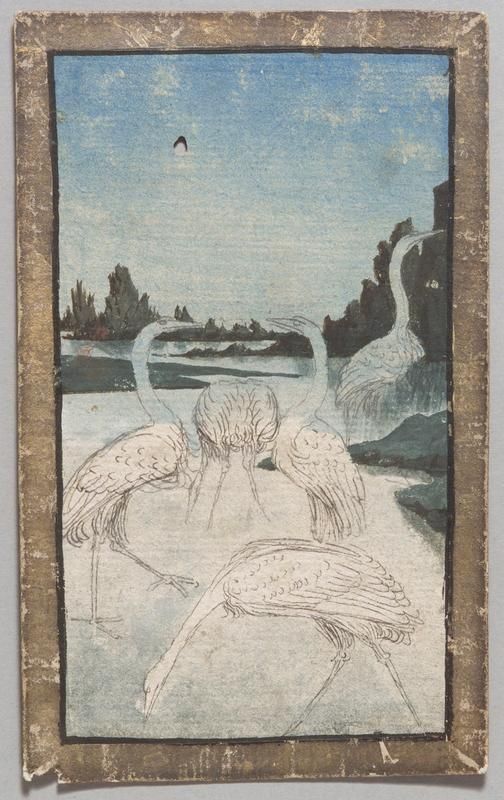

The Cloister's exhibit features several decks of cards, whose gilded backgrounds and careful lines make them appear like tiny paintings. The museum holds one set in its permanent collection, while the others in the exhibit are on loan. All were commissioned, the museum reports; most are from southern and southwestern Germany and in the Upper Rhineland. "Each deck reflects a differing worldview, slowly but inexorably shifting from nostalgic and idealized visions of a chivalric past to unvarnished and probing scrutiny of early Renaissance society," the exhibition's website explains.

Unlike modern card decks, those on display at the Cloisters do not have standard suits: falcons, hounds, stages and bears mark a hunting-themed deck. A late 15th-century deck from Germany uses acorns, leafs, hearts and bells. Kings, queens and knaves (knights, now) do appear on some decks, but also popular are clerics, fishmongers, chamberlains, heralds and cupbearers.

The World of Playing Cards writes that cards rather suddenly arrived to Europe around 1370 to 1380 and, seemingly just as swiftly, a ban on card games followed. The Church frowned upon cards, as they saw how the game promoted gambling. The World of Playing Cards references text from the special Register of Ordinances of the city of Barcelona, in December 1382, that prohibited games with dice and cards to be played in a town official's house, "subject to a fine of 10 'soldos' for each offense."

In 1423, St. Bernardino of Siena preached against the "vices of gaming in general and playing cars in particular" and urged his listeners to toss their cards in the fire. As the story goes, a card-maker then cried out, "I have not learned, father, any other business than that of painting cards, and if you deprive me of that, you deprive me of life and my destitute family of the means of earning a subsistence." St. Bernardino then directed the man to paint more sacred images.

Of course, card playing was never successfully quashed by degree or sermon and now, centuries later, they still serve their same initial purpose: to entertain and divert.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a9/07/a907255b-96d6-4765-ba54-8ff76d8104b7/ia-kk_5118_1.jpg)