Board of Sexism in Chess? Check Out These New Exhibitions

The World Chess Hall of Fame is showcasing the power of its women

When it comes to chess, the sole piece that symbolizes a woman—the queen—is the most powerful in the game. But often, female players are treated as second-class citizens in the male-dominated game. In an effort to change this perception, the World Chess Hall of Fame opened not one, but two exhibitions showcasing the power of women in chess at its facility in St. Louis, Missouri.

Both exhibitions are part of a larger initiative by the World Chess Hall of Fame to get women interested in chess. It’s an uphill battle: The game’s reputation of sexism has been underscored by incidents like grandmaster Nigel Short’s incendiary claims that women aren’t hardwired to play the game (something that Susan Polgar, the world’s first traditionally recognized female grandmaster, refutes). Despite the introduction of rankings focused on women and women’s-only championships, the game has historically found it difficult to attract—and retain—its women.

But that doesn’t mean women don’t play chess. The game has been around since at least the 6th century, but the first surviving reference to a female queen figure is from a poem written around 990. Since then, women have carved out their own niche on the board and in play against competitors of all sexes, as the World Chess Hall of Fame’s “Her Turn: Revolutionary Women of Chess” proves. The exhibition tracks the stories of women chess players from the 19th century through today. It follows the story of women like Nona Gaprindashvili, a Georgian player who may have been the best chess-playing woman in history, and the Polgar sisters, who grew up to support their father’s hypothesis that any healthy child could become a prodigy.

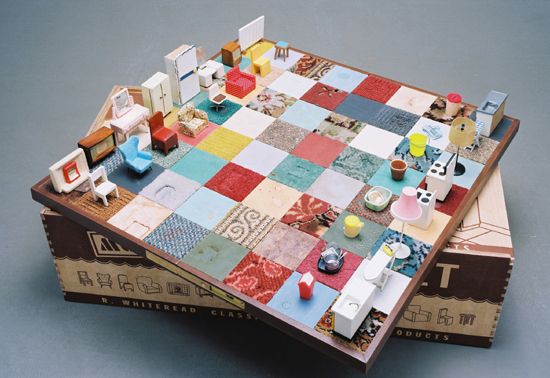

Meanwhile, the game’s artistic side is explored in another exhibit, “Ladies’ Knight: A Female Perspective on Chess.” Featuring artistic interpretations of chess boards by women artists, the exhibit shows that the game can be both a mental and a fine art. The World Chess Hall of Fame will also feature woman-focused classes, tournaments and events all year long. Will they lure even more women toward the game? Only time will tell. Meanwhile, the women who already love chess will keep doing what they do best—reigning over both the board and the competition.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)