After a Lifetime of Donkey Polo, This Chinese Noblewoman Asked to Be Buried With Her Steeds

New research reveals a Tang Dynasty woman’s love for sports—and big-eared, braying equids

:focal(2571x1748:2572x1749)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2b/81/2b812d93-3bed-421e-9989-fa8077169f51/gettyimages-582730618.jpg)

Donkeys tend to get a bad rap. Shorter, stockier and more floppy-eared than their majestic horse relatives, these plucky equids have been maligned throughout history—and in modern pop culture—as homely, stubborn dunces.

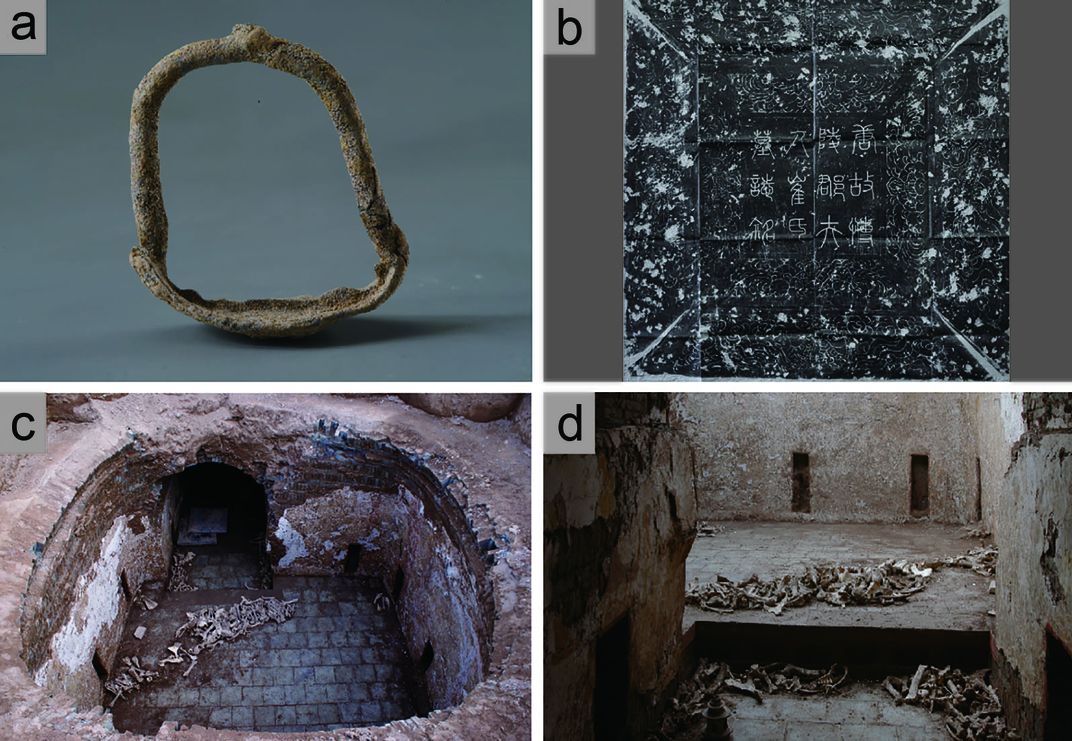

But were she still around today, a certain Tang Dynasty noblewoman would likely have a bone to pick with this derogatory trope—a whole grave full of bones, in fact. Cui Shi, a high-born lady who died in Xi’an, China, in 878 A.D., loved the pack animals so much that she requested to be buried with at least three of them. The faithful creatures likely served as her steeds during polo matches in life—perhaps to spare her the heightened dangers of playing the sport atop large horses, according to a study published this week in the journal Antiquity.

The findings mark the first physical evidence of donkey polo in Imperial China. Previously, the phenomenon was relegated only to historical texts, per a statement. They also buck societal expectations for the era—a time during which donkeys were already common pack animals, study author Fiona Marshall, an archaeologist at Washington University in St. Louis, tells Michael Price at Science magazine.

“Donkeys … are not associated with high-status people,” says Marshall, who helped unearth Cui Shi’s tomb in 2012, to Science. “They were animals used by ordinary folk.”

Cui Shi, however, found a more unusual—and noble—niche for the steadfast beasts. Both she and her husband, a high-ranking general named Bao Gao, were apparently whizzes at polo, a popular but dangerous sport that often injured or killed players who were bucked from their horses. Even Bao Gao, who attained status for his polo prowess, managed to lose an eye during a game, reports Ashley Strickland for CNN. And at least one Chinese emperor, Muzong, met a tragic end atop a horse during another ill-fated match.

To reduce the risk to riders, nobles came up with a polo variant called Lvju, swapping horses for donkeys, which were slower, steadier and lower to the ground, according to Science. Though Lvju was likely played alongside typical polo, to researchers’ knowledge, only the horse version of the sport was memorialized in art and artifacts.

Cui Shi didn’t draw up any donkeys in advance of her death. But it seems she was loathe to live an afterlife without them: Before she passed away at the age of 59 (likely not from a polo-related accident), she appears to have asked that several of the animals join her in her grave so she could continue her polo pastime into eternity, Marshall and her team argue in their study.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/60/35/60359e94-c546-44db-bae0-60747aa401c0/figure-5_final.jpg)

Though Cui Shi’s grave was eventually looted, the age of the animals’ bones, determined by radiocarbon dating, confirmed they’d been deposited around the time of her death. Stress marks also hinted that the donkeys had spent much of their life sprinting and turning—a hallmark, perhaps, of polo-playing equids—rather than trudging along, bearing heavy loads like pack animals. The donkeys were on the smaller side, which would have made them unsuitable for long journeys on hoof.

“This context provides evidence the donkeys in her tomb were for polo, not transport,” lead author Songmei Hu of the Shaanxi Academy of Archaeology tells CNN.

William Taylor, an anthropologist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, who wasn’t involved in the story, is more cautious, pointing out that alternative explanations exist for the bones’ unusual markings. While the donkeys could have played polo, they might also have engaged in pulling carts or milling grains, he explains in an interview with Science.

Either way, the researchers’ findings highlight the accomplishments of these often-underappreciated animals. As Sandra Olsen, an archaeologist at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, Museum of Natural History who wasn’t involved with the work, tells Science, “It is about time that donkeys are getting their due recognition.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)