Cave Dragons Exist—And Saving Them Could Be Key to Protecting Drinking Water

New DNA techniques are letting researchers track down the largest, strangest cave animals in the world

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a7/8e/a78e623a-fa87-429f-9bce-ed980694f433/img_1456jav.jpg)

In 2015, Gregor Aljančič almost died chasing cave dragons.

The head of the Tular Cave Laboratory, run by Slovenia's Society of Cave Biology, was diving in the underground passages of Planina Cave when he got trapped in a small air pocket. Nearly a mile underground, his oxygen dwindling, he made his best guess on the direction to safety. By a stroke of luck he ended up in another air pocket. Nearly four hours later, he found his colleagues—just before rescuers had arrived.

“The only reason he’s alive now is he found an air pocket in one of the crevasses and that kept him alive and he slowly worked his way back,” says Stanley Sessions, a biology professor at Hartwick College in New York state who has studied cave dragons with Aljančič in the Balkans. “It is just by the grace of proteus—the great olm in the sky—that he is alive today.”

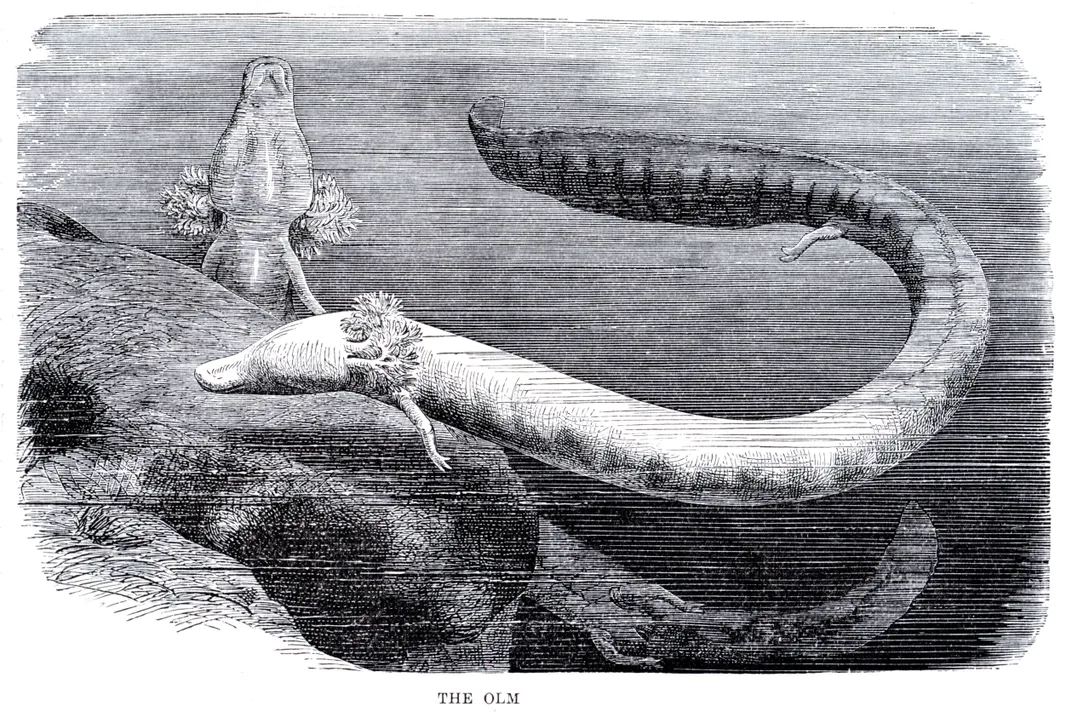

The blind cave dragon, as it is called, has long endeared biologists with its unparalleled weirdness. These snake-like amphibians sport small limbs, antler-like gills set back from their long snouts and translucent, pinkish-white skin that resembles human flesh. At up to 12 inches long, they are thought to be the world's largest cave animal. They live up to 70 years, the entirety of which they spend deep underground in the Dinaric Alps, which includes parts of Slovenia, Italy, Croatia and Herzegovina.

“I’m fascinated about their exceptional adaptation to the extreme environment of the caves,” says Gergely Balázs, a cave biology PhD student at the Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest who explores the caves where these dragons live. “And they are baby dragons, for God’s sake.”

Well, not exactly. In the past, on the odd occasion that flooding would wash one up to the surface, locals believed the unusual amphibians to be baby dragons—hence the nickname. One of the creature’s other monikers, proteus, stems from an early Greek sea god who had the ability to change shape. And while the origins of the German name (olm) are uncertain, the Slovenian name (človeška ribica) translates roughly to "human-fish."

You might think the obscure habitats of these legendary creatures would put them safely out of reach of human destruction. But their watery ecosystems collect the runoff from whatever drains down from the surface, meaning they still face habitat destruction due to development and hydroelectric projects which drain and reroute underground water supplies. Today they face increasing threats of pollution from agricultural runoff, not to mention the legacy of chemical waste plants.

“Karst is one of the most vulnerable landscapes on the planet,” Aljančič says, referring to the sinkhole- and cave-riddled limestone landscapes beneath which cave dragons make their homes. Moreover, focusing more effort on proteus conservation can also conserve water for Slovenians and for those in neighboring countries, he adds. After all, the same water that trickles down to the olm world is the source of drinking water for 96 percent of Slovenians.

“If they pollute the water and kill these guys off, it will be the biggest catastrophe of all time,” says Sessions.

Moreover, proteus are just the top of a diverse underground food chain that could also be killed off by pollution. “The caves in Slovenia are like tropical forests. They are biodiversity hotspots in terms of the number of species,” says Sessions. “And the species are cave-adapted so they are very, very strange.”

To help save a dragon, you first have to find it. That's a tall order when your subject lives in a vast underground maze of limestone passages. In an effort to simplify the search for dragons and increase scientists’ abilities to detect them, Aljančič and his colleagues are now using new environmental DNA sampling techniques, which pinpoint tiny traces of genetic material in water to figure out where the creatures hide without the need for cave diving.

Olms’ underground isolation has protected them from some of the major threats to amphibians of the few decades, such as human-influenced climate change and invasive fungal diseases. But now, it seems that the problems of the world above have reached the world below. “We need to know more about proteus and its habitat if we want to keep them both intact in future,” Aljančič. “New approaches in monitoring techniques such as eDNA (will) not only reduce the need of risky caving or cave diving, but even increase the quality of data collected in nature.”

Aljančič and his colleagues recently published one of the most extensive surveys of cave dragons to date, for which they sampled water downstream from hidden cave systems to identify a number of new populations in Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and the first ones known in Montenegro. To do so, they used a refined DNA technique that allows them to pinpoint proteus DNA strands mixed among a myriad of other genetic material in water. The technique also allowed them to detect proteus with a rarer black color in southern Slovenia, and to double the known range of this variety.

Despite the threats they face, proteus numbers can be vast. Sessions tells a story about biologists who were exploring some of the back recesses of the massive Postojna Cave—a famous Slovenian tourist attraction—when they came across an enormous underground cavern. “They found this big lake with echoing, dripping water; the only thing that was missing was Gollum,” he says. The lake’s bottom was entirely white, but as they approached, the color suddenly dispersed.

“It turned out that the bottom of the lake was completely carpeted with olms,” Sessions says. “This gives you an idea of how many of these things are out there.”

Cave dragons sit atop a complex cave food chain, which includes cave shrimp, spiders, arthropods, wood lice-type creatures and more. The predatory dragons will eat almost anything that fits in their mouth, but that doesn’t mean they always have an appetite, due in part to a very low metabolism; Sessions says that some researchers recently stumbled upon evidence that a captive individual had gone for a decade without eating.

Sessions, who was not involved in Aljančič’s recent study, says the new eDNA technique is a good way to detect proteus. “This study is taking a really non-invasive, non-destructive approach just sampling environmental water for fingerprint DNA,” he says. The technique is especially useful for finding proteus genetic traces in water, Balázs adds. It can help in situations where murky water makes it difficult for divers like him to see. “If you are just banging your head into rocks and you can’t find the way, it’s not fun,” he says. “And you don’t see the animals either.”

“Science is all about the how and why,” Balázs continued in a follow-up email. “We need to know how strong the population is. Are they healthy? Can we find juveniles? ... We have no information what they do in real life, in nature. It’s really hard to observe.”

So will Aljančič and team’s advances in using environmental DNA to detect detection soon make cave diving obsolete? Not likely, says Balázs, who was involved in a tagging study of the animals in 2015. After all, eDNA is a useful and affordable tool, but it only gives biologists a rough idea of where there be dragons. Divers still need to hunt them down.

To do so, Balázs has squeezed through nearly 50 cracks in the karst and underwater tunnels, chimneys and caves in what he calls “a labyrinth of restriction” of Bosnia and Herzegovina for the better part of 15 years. While cave diving purely for the sake of exploration can be difficult, he says, cave diving to search for proteus is even harder since the snake-like creatures can take refuge in tiny, cracks in the rock difficult to access by humans.

Yet matter how much we find out about them, it's likely that cave dragons will still fill us with mystery and wonder. “They do nothing,” says Balázs. “They live in strange places, not moving for years.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joshua-learn_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joshua-learn_copy.jpg)