Energy Saving Lessons From Around the World

The curator of an exhibit at the National Building Museum highlights case studies of community involvement in energy conservation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/solar-panels-Sanso-Island-Denmark-631.jpg)

An architect by training, Susan Piedmont-Palladino is the curator of Green Community, a new exhibit at Washington, D.C.'s National Building Museum that showcases what communities around the world are doing to build a sustainable future. From public transportation to repurposing old buildings to taking advantage of natural resources, the localities selected by Piedmont-Palladino and her advisory team exemplify the forefront of the green movement. She discussed the exhibit with Smithsonian's Brian Wolly.

How did you select these communities?

That was probably the biggest issue, because we are covering a topic that so many cities, towns, homes are doing something about, and many are doing a lot. But we wanted to try and find some communities from geographic areas that had been underrepresented. The tendency is to look to the coasts and to Western Europe and maybe Asia and so we deliberately looked south to see what was going on in Latin America, looked into the interior of the country to see some stories that hadn't been told.

We were looking for good stories and clear stories that we could communicate with the public and we were also looking for such a wide range that anyone who came to the exhibit could find something that they recognized as a place that they might live. We think we covered everything from Masdar City [in the United Arab Emirates], which is the glamour project, the most forward-looking and most aspirational—it's also the least-proven because they've only just broken ground—all the way down to Stella, Missouri or Starkville, Mississippi, which are the tiniest grassroots efforts.

How is the exhibit itself an example of green building?

We realized to do this [exhibit], we needed to walk the walk that we were talking. We had all new LED lighting, which we got some funding for in a grant through the Home Depot foundation, which has really helped us to green our building. Most of the cases are made from eco-glass, which is recycled glass that then can be recycled once again. We used steel, because that has such a high recycled content, along with recycled carpet and cork.

One of the other decisions that we made, which always strikes museum professionals as rather curious, is we opened up the entire exhibition to natural light. We don't have any original works on paper, anything that needs protection from light. We wanted to remind visitors that they are in the city while they are in this other world of the exhibition space. The ambient light is natural daylight, and so the cases can be lit on very low levels.

What are some of the communities doing to harvest natural resources like wind, solar or hydropower?

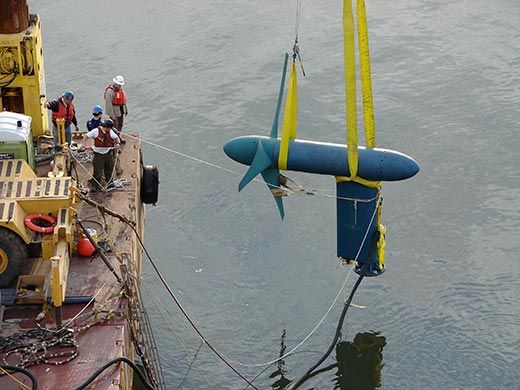

Copenhagen has its wind farm that is so beautiful; from space you can see it via Google Earth. There's a damless hydropower [project] that's being tested in the East River, a way for New York to use the tidal power of the river without actually putting in any dams.

The community in Hawaii, Hali'imaile, Hawaii is looking at the orientation of their development for solar and wind purposes, and then looking at the design of each building in that community. In that sense, harvesting natural resources trickles down through the master plan all the way into the buildings.

What are some of the quickest ways that towns and cities can become more energy-efficient?

There's a wonderful quote by Auguste Rodin, the artist, "What takes time, time respects." Unfortunately, the best efforts are really long-term efforts: they have to do with changing land-use policies, investing in mass transit and public transportation, disincentives for all sorts of other behaviors.

But on the quick list? Looking at empty lots and unclaimed land, thinking about ways to encourage people to use community gardens and local agriculture. Those are things that are seasonal and get people thinking about their environment. There are also recycling programs; cities can upgrade their street lights—there are new designs for LED street lighting—and all sorts of ways that infrastructure in the cities can be adapted.

What can people do on their own to get engaged in their hometown's city plans?

I think that embedded in the show, the message is, "get active." That can be going to your city council meetings, joining one of the civic boards that oversees decisions. Sometimes people are mobilized to prevent things from happening. That's often what gets people active in the first place, preventing a building they don't want, preventing a building from being torn down. And that sense of empowerment and action hopefully keeps people engaged. In the end, active participation is the only way to make change. That sounds like politics, and I guess it is politics, but I guess that's where design and planning find themselves enmeshed in how public policy gets formulated and changed.

There's an education barrier too, to how these decisions are made.

Right, as in, "this is the world that's given." There is a sense of some nameless "they," a third person plural that made it all happen and that is keeping it going as it is. One of the messages that we wanted to get across with this exhibit is that you have to change that third person plural to a first person plural. There's no "they," it's a "we." The community is nothing other than the people that make it up. Green doesn't happen without the community.

Sometimes discussions of green building gets bogged down in stereotypes of hippies versus industry, as if this were just a recent debate. But many of the aspects of green communities are as old as civilization itself.

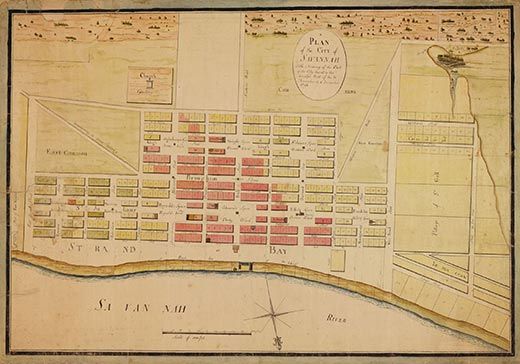

Hopefully the range of communities we've exhibited has managed to elide some of those distinctions. We've also included some historic examples: we talk about the urban design of Savannah way back in the 18th century, and then we show a photograph of the contemporary city and you can find the same squares and the same virtues. Same thing talking about Mendoza, Argentina, which found a beautiful way to manage its water supply and in the process made the city habitable in an otherwise extremely hot, dry environment.

With the economic recession, there may be a lot of resistance to investing in some of the initiatives showcased in the exhibit. What argument would you make to a state or city budget meeting about the need for green building?

Now is the time to go ahead and say, "look, we only have so much money, we can either make the hard choices that are going to see us through generations of doing things right. Or we're going to continue to do things wrong." And it's very hard to fix problems on the urban planning and infrastructure scale. If you do it wrong, you inherit that problem forever. Sprawl is one of those, all these decisions are with us for a long time. Ultimately, the green decisions are the decisions that are most frugal. They may seem expensive or inconvenient, but in the end it will actually save us the most in terms of capital resources and human capital.

I did an interview with [architect] Paolo Soleri for the Building Museum's magazine; he got a lifetime achievement award at the Smithsonian's Cooper Hewitt Design Museum that year [in 2005]. I asked him when did he start thinking about these things, living differently, and his whole theory about Italy and we're known for being cheap."

I just thought that was a delightfully refreshing idea, it didn't really come from any lofty ideology; it came with a sense of frugality.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/brian.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/brian.png)