Turning Dragonflies Into Drones

The DragonflEye project equips the insects with solar-powered backpacks that control their flight

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/38/bd/38bd5ba3-96f8-493e-a734-f6011af2c771/dragonfleye.jpg)

If “dragonfly drones wearing tiny backpacks” doesn’t say “the future is here,” what does?

A project called DragonflEye, conducted by the research and development organization Draper in conjunction with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, is turning the insects into hybrid drones. Live dragonflies are equipped with backpacks containing navigation systems, which tap directly into their nervous systems. The dragonflies can then be “steered” to fly in certain directions. The whole thing is powered by miniature solar panels in the backpacks.

The backpack-wearing dragonflies become living “micro air vehicles,” or tiny drones. These kinds of drones have the potential to work where larger ones can’t, flying indoors or in crowded environments.

Scientists have tried to control insect flight before, explains Joseph J. Register, a biomedical engineer at Draper and senior researcher on the DragonflEye program.

“Previous attempts to control insects have mostly relied on spoofing of the peripheral nervous system or directly shocking the flight muscles to augment flight,” Register says. “We are adapting a more centralized approach where we plan to optically stimulate ‘flight specific’ nerves.”

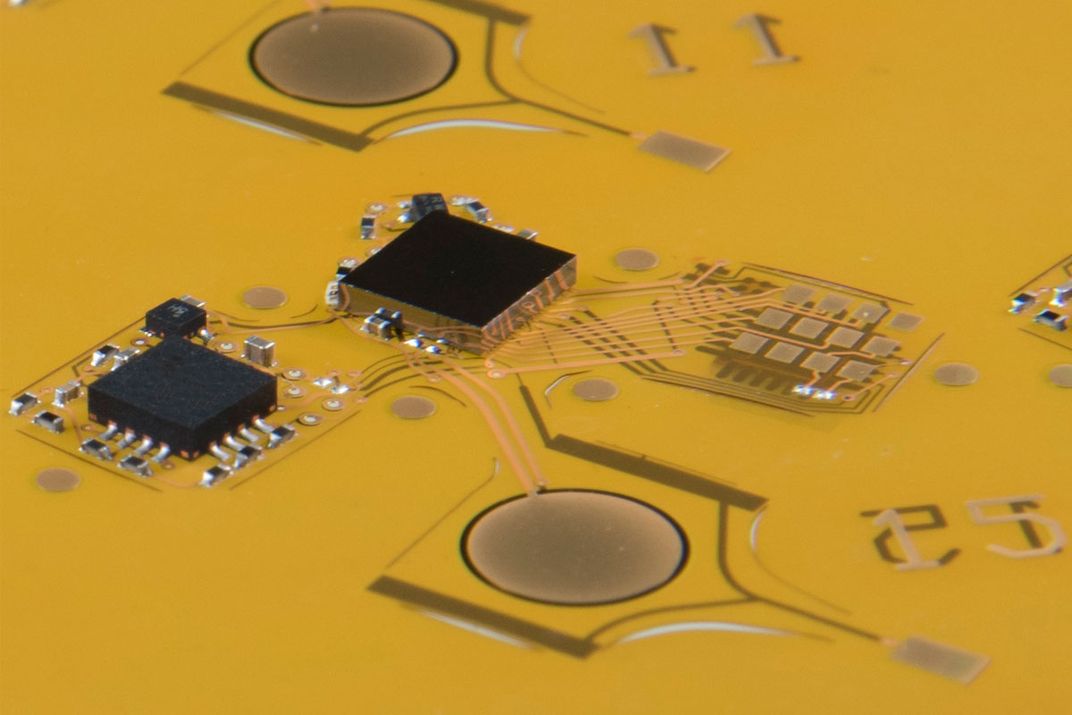

To do this, the researchers have made the dragonflies’ steering neurons light sensitive by inserting genes similar to those found in their eyes. Then tiny structures called optrodes in the backpack emit pulses of light that activate the steering neurons. These neurons in turn activate the muscles that operate the insects' wings. These optrodes are so sensitive they can target only the steering neurons without disrupting other nearby neurons.

Dragonflies are the ideal insects to be used as drones, researchers say.

“Dragonflies are the best fliers of the insect world,” says Jess Wheeler, a biomedical engineer at Draper and principal investigator on the DragonflEye program. “Due to highly evolved wing morphology, dragonflies allow for not only fast flight but also gliding, hovering and backwards flight. This allows for a very maneuverable platform.”

Dragonflies are able to fly thousands of miles over land and water, reaching altitudes as high as 6,000 meters, Wheeler says. This gives them a major advantage over manmade micro air vehicles, which can usually only fly for a few minutes at a time.

The backpacks affect the dragonflies less than you might expect. The backpack adds a bit of weight and slightly affects the insects’ center of gravity. But the changes aren’t enough to affect the dragonflies’ natural behaviors and flight mechanics, allowing them to continue snacking on mosquitoes as usual.

The DragonflEye platform could have any number of uses, researchers say.

“Some uses we can’t even envision yet, but we can see applications ranging from remote environment monitoring, search and rescue in dangerous buildings, and crop pollination on a large scale,” Wheeler says.

This optrode technology could one day be used for biomedical purposes too, by targeting human neurons for diagnostic or therapeutic uses.

They could also potentially be used for surveillance—after all, who would notice an insect buzzing overhead?

The DragonfEye technology could be transferred to other insects, researchers say. Honeybees would be a natural choice, given the collapse of their population levels and their importance as pollinators. The technology could in theory steer insects to pollinate in certain areas, helping save crops that would otherwise be lost.

Right now, though, the team is focused on hashing out the basics of navigation and control. The team plans to begin testing and collecting data within the year.

“Once we have established some basic navigational datasets we can move on to larger applications,” says Register.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)