Coming in 2015: A Faster, Sharper Way to 3D Print

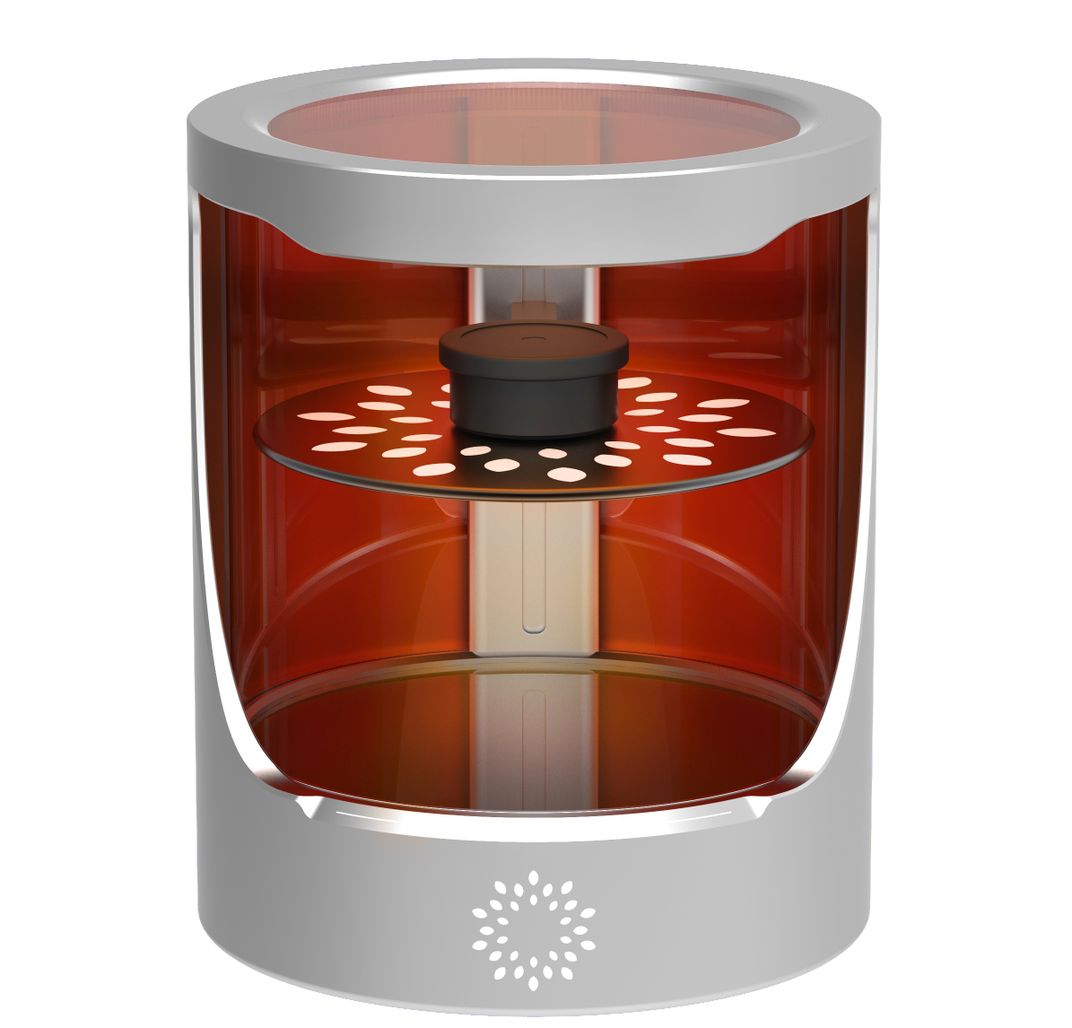

Orange Maker’s Helios One prints in a spiral, as opposed to layer by layer, making the entire process more efficient

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/77/be/77be9b1b-d7ae-4347-9510-845da7076c2a/orange-maker-heliolithography-prototype.jpg)

Even though 3D printing has moved into the spotlight (Gartner estimates that shipments will double year-over-year), the rapid-prototyping revolution it's sparked has actually been brewing for decades. In fact, many of the names that are now synonymous with the method—we're looking at you MakerBot and FormLabs—have built their machines on pre-existing patents and technologies.

Many consumer and commercial 3D printers work off of a system called stereolithography (SLA, for short), which was first patented in 1986. The machines use UV light to harden thin layers of resin one by one. The object needs to lift off of the platform before the printer can move on to the next layer.

Using SLA isn't exactly ideal. Chief among the reasons: speed and detail. So California startup Orange Maker is introducing a new spin on 3D printing. The company's method, called heliolithography, claims to print objects faster and with greater accuracy than ever before.

“There’s a big gap between what people want to create and what they actually get in the real world,” says Kurt Dudley, of Orange Maker, who, together with co-founders Doug Farber and Chris Marion, has been working on the Helios One since 2011.

The problem with SLA printing, he says, is that when the model lifts off the platform between layers, adhesion forces can rip it, causing defects and failed prints.

The core idea of the Helios One, a desktop 3D printer that Orange Maker plans to release in 2015, is that it can print continuously. Instead of moving a light source back and forth across layers of resin, the platform on the Helios One rotates as resin hits the surface. Objects are printed in a spiral instead of as one flat layer on top of another. In doing this, the printer doesn’t need to pause as it severs resin between layers. The development team also traded in the standard SLA light source, UV lasers, in favor of one they say is better suited for continuous printing. Though the team won't reveal what the light source is, they claim it reduces the risk of botched prints.

Farber is quick to note that while those are the primary differences, his company has completely re-engineered the process as we know it.

“Everything about the system has been re-imagined and optimized,” he says. “You can’t just add a rotating build platform to a SLA system and have that work. It’s an entirely different method.”

The most immediate advantage of the Helios One seems to be its speed. Though he wouldn't quote specific gains, Dudley does encourage some mental math: Multiply the many hundreds of layers that make up a 3D print by the time it takes for the printer to reset between layers (say, between 1 and 3 seconds). “It makes a significant difference,” he states.

While the standard SLA process is faster than traditional manufacturing methods, it can still be very slow. It takes the FormLabs Form 1 printer six hours to print a chess piece, according to TechCrunch, and the Unirapid III printer took 30 minutes to complete a 2.5-milimeter cube.

So what can you print with the Helios One, anyway? The printer can handle the same designs and file formats that its competitors can—think teacups and other palm-sized knicknacks—but according to Farber and Dudley, it will make them all with a greater level of fidelity and detail.

The print area is similar to most current-generation consumer desktop 3D printers—maybe a 6-inch square—but Orange Maker says the system is scalable.

“It’s a foundational system,” Farber says, which means, in theory, companies could someday use the technology to build things like houses.

Compared to fused-deposition modeling (FDM), the method used by MakerBot printers to print everyday objects like iPhone stands and figurines, Dudley says that heliolithography can handle larger prints, such as chairs and replicas of large-scale sculptures.

“In an FDM printer, the nozzle has to travel and cover the entire area; we’re able to solidify and bevel large volumes of resin all at the same time,” Dudley explains. “In that way, it has super scalability compared to pretty much anything on the market.”

While they’re focused on the Helios One launch right now, the founders also see potential to incorporate materials other than plastic resin—metals, perhaps—into their process in the future.

“It’s not just about how the machine works,” Dudley states, “it’s just as important to be able to print in a wide variety of materials.”

Details about Orange Maker’s debut, though, are scarce, which has bred skepticism among 3D-printing devotees.

“The announcement is an impressive one, but we’ll have to wait to hear more from the company, including specs about the Helios One and more details about how the heliolithography process works,” writes Michael Molitch-Hou, founder of The Reality Institute and contributor at 3D Industry News. “We’ve been burned by other 3D printer manufacturers in the past.”

For Dudley and Farber's part, they say the company has a manufacturing partner in place, and they are confident that they’re on track to deliver their first printers next year.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/me.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/me.jpg)