The Irresistible Bonnie Parker

A pistol-wielding, cigar-chomping bank robber hams it up shortly before she and Clyde Barrow met their violent end

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Bonnie-Parker-WD-Jones-631.jpg)

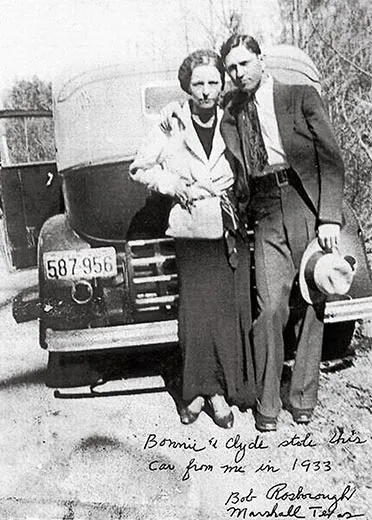

Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker began 1933 on what for them passed as a high note. They'd been fugitives for months as Clyde and some accomplices robbed and shot their way around Dallas and environs, and Clyde had barely escaped a police ambush at a friend's West Dallas home. But after he got away (killing a sheriff's deputy in the process), he and Bonnie spent three months roaming Oklahoma, Arkansas and Missouri, with their partner W.D. Jones, anonymous and unhurried.

This period came closest to the carefree criminal life the couple had envisioned after Clyde was paroled from a Texas prison farm in February 1932. Unbothered by any organized pursuit, they meandered from town to town, stealing cash and food as needed. They ate by the roadside or in the privacy of rented rooms. Bonnie felt safe enough to forgo flat shoes (easier to run in) for the high heels she preferred.

Later on, Clyde's sister Marie would muse that during these months the members of the so-called Barrow Gang wielded a screwdriver more often than they did their guns. They used the tool to change license plates to evade identification on the cars they stole. Clyde drove; Bonnie navigated. W.D. was often called on to act as photographer.

Clyde and Bonnie loved posing for pictures. Sometimes they'd strike the same sort of silly poses they'd assumed in a more innocent time in the amusement park photo booths back in Dallas (when the guns they waved were toys). One photograph W.D. snapped showed Bonnie posing with a gun in her hand and a cigar clenched in her teeth. "Bonnie smoked cigarettes, but...I gave her my cigar to hold," he would later say.

At that moment, the notoriety of the Barrow Gang was concentrated in Texas, with faint radiations into select parts of New Mexico and Oklahoma. That would soon change.

On April 13, 1933, police in Joplin, Missouri, raided an apartment in that town in the belief they would find some bootleggers there. (Prohibition wasn't quite over in Missouri; beer was legal, spirits weren't.) Instead, they found Clyde, Bonnie and W.D., along with Clyde's brother Buck and sister-in-law Blanche, who had met up with the others after Buck's own release from prison.

A firefight broke out. Two police officers were shot dead. Although W.D. took a bullet in the side (from which he would recover), all five members of the Barrow traveling party escaped. Clyde drove them to Shamrock, Texas, covering almost 600 miles overnight. They had only the smoking guns and the clothes on their backs.

Back at the Joplin apartment, police discovered a camera and some rolls of undeveloped film. After processing, the film yielded a series of prints depicting all five fugitives. The one of Bonnie with the gun and the cigar was among several the Joplin Globe published just two days after the raid—then sent out over the wires.

The Joplin photographs introduced the nation to new criminal superstars. Of course there were others—Al Capone, Ma Barker, John Dillinger, Pretty Boy Floyd—but in Clyde and Bonnie the public had something new to ponder: the idea of illicit sex. The pair were young and traveling together without benefit of marriage. And while ladies smoked cigarettes, this gal smoked a cigar, Freudian implications and all.

Articles on the pair soon appeared in such magazines as True Detective Mysteries. The newsreels weren't far behind. Bonnie and Clyde were on their way to becoming folk heroes to a Depression-weary public. "Even if you did not approve of them," recalls Jim Wright, the former speaker of the House of Representatives who grew up in Texas and Oklahoma at the time, "you still would have to envy them a little, to be so good-looking and rich and happy."

But the couple's final 13 months belied their new image. They spent the time in the company of a shifting cast of thugs. (They eventually parted ways with W.D., who that November went to prison for killing a sheriff's deputy.) They robbed small-town banks and mom-and-pop stores, or tried to. They sometimes broke into gum ball machines for meal money. Their celebrity had made them the target of lawmen across the Mid- and Southwest.

In February 1934, authorities in the Lone Star State hired former Texas Ranger Frank Hamer to track them down, and with information from a Barrow Gang member's family, he did just that. Clyde and Bonnie were alone together on May 23, 1934, 75 years ago next month, when they drove a stolen Ford sedan into a spectacularly fatal police fusillade outside Gibsland, Louisiana. He was 24, she 23.

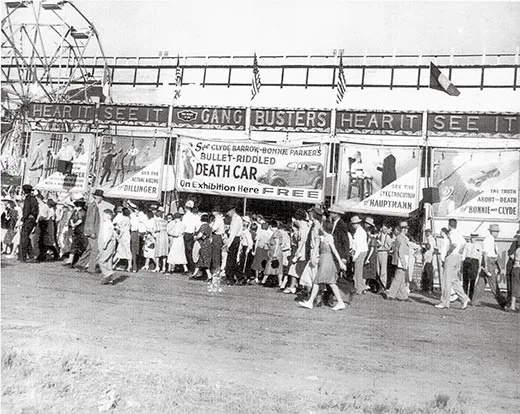

The allure of their image outlived them. A crowd of 10,000 overran the funeral home where Clyde's body was laid out; twice as many, in the estimate of Bonnie's mother, filed past her casket. Afterward, an entrepreneur bought the bullet-riddled Ford and toured it for years, into the early '40s. People lined up to see it.

Jeff Guinn, a former investigative reporter for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, has written 14 fiction and nonfiction books.

Adapted from Go Down Together, by Jeff Guinn. Copyright © 2009 by Jeff Guinn. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster Inc., New York.