In Search of George Washington Carver’s True Legacy

The famed agriculturalist deserves to be known for much more than peanuts

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e4/c1/e4c1a9eb-ffd2-4df6-8030-9e3ebcb74ce0/gettyimages-515180964.jpg)

If the name George Washington Carver conjures up any spark of recognition, it’s probably associated with peanuts. That isn’t an unfair connection—he did earn the nickname “the peanut man” for his work with the legume—but it’s one that doesn’t give credit to the rest of Carver’s pioneering, fascinating work.

“People, when they think of Carver, they think of his science—or they think he invented peanuts,” says Curtis Gregory, a park ranger at the George Washington Carver National Monument at Carver’s birthplace in Diamond, Missouri. “There’s so much more to the man.”

Mark Hersey, a history professor at Mississippi State University and author of an environmental biography of Carver, says that “[Carver] became famous for things he probably shouldn’t have been famous for, and that fame obscured the reasons we should remember him.” In Hersey’s view, the contributions Carver made to the environmental movement, including his ahead-of-the-times ideas about self-sufficiency and sustainability, are far more important than the “cook-stove chemistry” he engaged in.

Nonetheless, Carver became ludicrously famous for his peanut work—possibly the most famous black man in America for a while. Upon his death in 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt remarked on his passing: “The world of science has lost one of its most eminent figures,” he said.

***

Carver was born enslaved in western rural Missouri, orphaned as an infant and freed shortly after the Civil War. Sometime in his 20s, Carver moved to Iowa where a white couple he met encouraged him to pursue higher education. Carver’s education before this had been largely patchy and self-taught; at Simpson College in central Iowa, he studied art until a teacher encouraged him to enroll at Iowa State Agricultural College to study botany. There, he became the school’s first African-American student.

Founded in 1858, Iowa State Agricultural College (now Iowa State University) was the country’s first land-grant university, a group of schools with a mission to teach not just the liberal arts but the applied sciences, too, including agriculture. There, students studied soils, entomology, analytical and agricultural chemistry, practical agriculture, landscape gardening and rural architecture, in addition to more basic subjects like algebra, bookkeeping, geography and psychology.

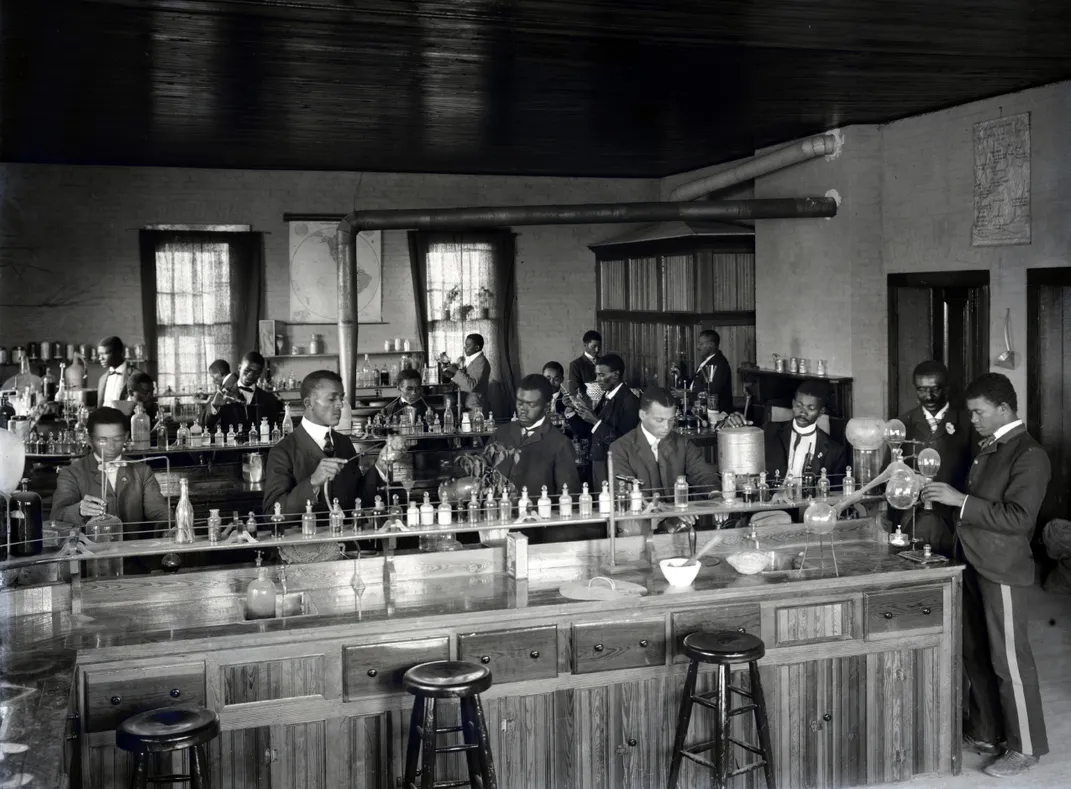

Upon graduation from Iowa State in 1896, Carver was bombarded with offers to teach. The most attractive was that from Booker T. Washington, the first leader of the Tuskegee Institute, which was opening an agricultural school. As the first black man in the U.S. to receive graduate training in modern agricultural methods, Carver was the logical choice for the role. He accepted, writing that “it has always been the one great ideal of my life to be of the greatest good to the greatest number of ‘my people’ possible and to this end I have been preparing myself these many years; feeling as I do that this line of education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom to our people.”

As Carver rode the train to Alabama, however, his heart sank. In a 1941 radio broadcast, he recalled: “My train left the golden wheat fields and the tall green corn of Iowa for the acres of cotton, nothing but cotton, ... ... The scraggly cotton grew close up to the cabin doors; a few lonesome collards, the only sign of vegetables; stunted cattle, boney mules; fields and hill sides cracked and scarred with gullies and deep ruts ... Not much evidence of scientific farming anywhere. Everything looked hungry: the land, the cotton, the cattle, and the people.”

What Carver understood was that cotton, while lucrative, did nothing to replenish the soil. It’s not the most demanding crop, but its shallow roots, and the practice of monocropping, mean that soil erodes faster from a cotton field than if the earth was left alone. (Carver later would describe eroded gullies on the Tuskeegee campus that were deep enough for a person to stand inside.)

What he failed to understand, however, were the political and social forces he would be up against.

“He’s enormously arrogant when he comes down,” Hersey says. “It’s an innocent arrogance, if anything.” At Tuskegee, Carver published and distributed bulletins suggesting farmers buy a second horse to run a two-horse plow, which could till soil deeper, and described commercial fertilizers “as if people have never heard of them.” Most of the poor sharecropping black farmers had heard of fertilizer, but couldn’t scrape together the money to buy any, let alone a second horse.

“And then it dawns on him,” says Hersey. In turn-of-the-century Alabama, black farmers lived a precarious existence, ever-threatened by unevenly enforced laws that disproportionately harmed blacks. After the Civil War, Southern landowners “allowed” poor farmers, mostly blacks, to work their land in exchange for a fee or a cut of the crop. The system was precarious—one bad year could push a farmer into ruinous debt—and unfair: One historian called it “a system of near slavery without legal sanctions.” Near Tuskegee, one tenant farmer was arrested “for chopping wood too close to the property line,” Hersey says. While the farmer remained in jail, whites put up his farm for sale. When tenants didn’t control their land and could be evicted at any time—or kicked off their land on trumped-up charges—they had little incentive to improve the soil.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ea/5f/ea5f84ad-fd2b-4a0a-8172-0c96dc65bee7/gettyimages-515176998.jpg)

Still, Carver got to work. He worked tirelessly—the Carver Monument says from 4 a.m. to 9 p.m. some days—on improving crop yields and encouraging farmers to diversify. That, too, was tough: Financially lucrative cotton, Hersey says, was seen as the only crop that could get tenants out of debt. Carver encouraged farmers to grow, or at the very least forage, their own vegetables and proteins so they would spend less money on food. Later, he developed and implemented the Jesup Agricultural Wagon, a school-on-wheels that brought agricultural equipment and demonstration materials to rural farmers unable to travel. The wagon reached 2,000 people a month in its first summer of operations, in 1906.

“What Carver comes to see,” Hersey says, was that “altering [black sharecroppers’] interactions with the natural world could undermine the very pillars of Jim Crow.” Hersey argues that black Southerners viewed their lives under Jim Crow through an environmental lens. “If we want to understand their day to day lives, it’s not separate drinking fountains, it’s ‘How do I make a living on this soil, under these circumstances, where I’m not protected’“ by the institutions that are supposed to protect its citizens? Carver encouraged farmers to look to the land for what they needed, rather than going into debt buying fertilizer (and paint, and soap, and other necessities—and food). Instead of buying the fertilizer that “scientific agriculture” told them to buy, farmers should compost. In lieu of buying paint, they should make it themselves from clay and soybeans.

“He gave black farmers a means of staying on the land. We all couldn’t move north to Chicago and New York,” Michael Twitty, a culinary historian, told the Chicago Tribune.

And that’s where the peanuts come in. Peanuts could be grown in the same fields as cotton, because their productive times of year were different. While some plants need to be fertilized with nitrogen, peanuts can produce their own, thanks to a symbiotic relationship with bacteria that live on their roots. That special trait meant they could restore nutrients to depleted soil, and they were “an enormously rich food source,” high in protein and more nutritious than the “3M--meat, meal and molasses” diet that most poor farmers subsisted on.

Carver encouraged farmers to grow peanuts, but then he had to encourage them to do something with those peanuts, hence his famous “300 uses for peanuts.” Carver’s peanut work led him to create peanut bread, peanut cookies, peanut sausage, peanut ice cream, and even peanut coffee. He patented a peanut-butter-based face cream, and created peanut-based shampoo, dyes and paints, and even the frightening-sounding “peanut nitroglycerine.”

However, this number may be a little inflated. Of the roughly 300 uses for the peanut (the Carver Museum at Tuskegee gives 287) Carver detailed, “many…were clearly not original,” such as a recipe for salted peanuts, historian Barry Mackintosh wrote in American Heritage in 1977 on the occasion of the election of peanut-farmer Jimmy Carter as president. Others he may have gotten from contemporary cookbooks or magazines; at the beginning of “How To Grow The Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing It For Human Consumption“ Carver “gratefully acknowledge[s] assistance” from more than 20 sources, including Good Housekeeping, The Montgomery Advertiser, Wallace’s Farmer and a number of other magazines, newspapers and cookbooks.

Yet Carver had no illusions about his work. He wasn’t trying to create “the best” products—or even wholly original ones, as few of his creations were—but to disseminate information and recipes that could be made by poor farmers with few tools or resources.

He cared about helping what he called “the furthest man down,” says Gregory.

Carver’s student John Sutton, who worked with him in his lab around 1919, recalled:

When I could not find the “real” scientist in him, I became hurt.... I should have known better since time and again he made it clear to me that he was primarily an artist who created good ... out of natural things. He knew that he was not “a real chemist” so-called engaged in even applied chemical research. He used to say to me jokingly, “You and I are ‘cook-stove chemists’ but we dare not admit it, because it would damage the publicity that Dr. Moton [Booker T. Washington’s successor] and his assistants send out in press releases about me and my research, for his money-raising campaigns.”

Carver’s ubiquitous association with peanuts is in many ways due to the explosive testimony he delivered before Congress in favor of a peanut tariff. In 1921, the U.S. House Ways and Means Committee asked Carver to testify on a proposed tariff on imported peanuts. Expecting an uneducated backwoodsman, the committee was blown away by the soft-spoken scientist.

“He’s had thousands of public speaking appearances at this point,” Hersey says. “He can handle it all. [Congress] is making watermelon jokes, but they’re not saying anything he hasn’t already heard at the Georgia State Fair.” The tariff on imported peanuts stuck, and Carver became, in Hersey’s words, “a rockstar.”

Late in his life, a visitor asked Carver if he believed his peanut work was his greatest work. “No,” he replied, “but it has been featured more than my other work.”

So what was his work? Hersey argues it was a way of thinking holistically about the environment, and an understanding, well before it had reached mainstream thought, of the interconnectedness between the health of the land and the health of the people who lived on it. “His campaign is to open your eyes to the world around you,” Hersey says, to understand, in Carver’s phrase, “the mutual dependency of the animal, vegetable, and mineral kingdoms.” But that doesn’t make for good soundbites, even today.

It’s not as catchy as 300 uses for peanuts, but years before the environmental movement took hold, Twitty told the Tribune, “Carver knew the value of working the land, of being with the land, of working with each other.”