The “Scandalous” Quarter Protest That Wasn’t

Were Americans really so outraged by a semi-topless Lady Liberty that the U.S. Mint had to censor this coin?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5b/99/5b990786-0ba5-4be7-b8e9-f67c52bba163/25335720_31837063_2200-wr.jpg)

It started out innocently enough: In January 1917, the United States released a new quarter dollar it had minted at the end of the previous year. Just 52,000 copies of the 1916-dated quarter were produced.

But this was no ordinary coin. Instead, it would become one of the most legendary and sought-after in American history. The reason: a single bare breast on Lady Liberty.

From the first, the coin was a big hit. “Crowds Flock to Get New Quarters,” noted a New York Sun headline on January 17, 1917. “Miss Liberty’s Form Shown Plainly, to Say Least,” the Sun added, suggesting that Liberty's anatomy might have something to do with the coin’s popularity.

Indeed, the goddess’s garb gave newspapers across the land something to huff and/or snicker about. The Wall Street Journal primly observed that, “Liberty as attired on the new quarter just draws the line at license.” An Iowa newspaper sniffed about the “almost nude figure of a woman,” saying, “We can see no use in the government parading such pieces of art before the public."

An Ohio paper was a little more whimsical, observing that Liberty was “clad something after the manner of Annette Kellerman,” referring to a famous swimmer turned silent actress of the day who was supposedly the first star to appear naked in a Hollywood movie. (Alas, that 1916 film, A Daughter of the Gods, has been lost to time, like so many of its era.)

The Los Angeles Times, meanwhile, reported that few buyers of the new coin in that city “found anything in her state of dress or undress to get excited about. In fact, Miss Liberty is dressed up like a plush horse compared to the Venus de Milo.”

Prohibitionists meeting in Chicago, whose moral concerns apparently went beyond demon rum, may have been the group that condemned the coin most severely. “There is plenty of room for more clothes on the figure,” one Prohibitionist leader told reporters. “I do not approve of its nudity.”

But a letter-to-the-editor writer in Tacoma, Washington rose to Liberty’s defense. “I wonder why some people are always seeing evil in everything,” he said. “There are so many people who would be so thankful to have the quarter they would not notice or care about the draperies.”

Eventually, the Prohibitionists got their wish. Though additional bare-breasted quarters were issued in 1917, later that year a new redesign went into circulation. The offending bosom was now covered with chainmail armor.

In the ensuing decades, the story would evolve from one of bemusement and mild protest in some “quarters” to a tale of national outrage. By the late 20th century, the standard account had everything but irate mobs storming the U.S. Mint with pitchforks and flaming torches.

Writers now repeated the tale of widespread public “uproar.” Adjectives like “scandalous,” “naughty,” and “risqué” popped up in nearly every article. One price guide referred to it as “America’s first ‘obscene’ coin.” A major auction house with a collection of quarters for sale called it a “Scandalous Rare Coin That Created Moral Outrage.”

Some accounts even claimed that famous anti-vice crusader Anthony Comstock had personally led the attack against the coin. The only problem with that story? Comstock died in 1915.

Not that he wouldn’t have joined in if he could. A longtime foe of scantily clad mythological figures, Comstock once unsuccessfully pressed for the removal of a gilded,13-foot-tall and totally naked statue of the Roman goddess Diana mounted atop Manhattan’s Madison Square Garden.

After decades of hype, a new generation of writers has finally taken a closer look at the alleged coin contretemps. One of them is Robert R. Van Ryzin, currently the editor of Coins magazine.

Van Ryzin says he grew up believing the Liberty legend as a young collector. When he began writing about coins professionally, though, he could find little evidence that large numbers of Americans were incensed by a 25-cent piece—or that their complaints were the reason the Mint altered the coin.

“I don’t know who started it,” he says of the long-accepted story. “But I suspect it was easy for people to believe such a thing.” In other words, it made sense to modern Americans that their 1917 counterparts were so prudish that they could be shocked by their pocket change.

In fact, contemporary news accounts show nearly as much griping about the depiction of the eagle on one side of the quarter as about Liberty on the other.

Squawked one bird buff: “It is well known that the eagle in flight carries his talons immediately under his body, ready for a spring, whereas in the quarter dollar eagle the talons are thrown back like the feet of a dove.”

Other critics charged that the design of the coin made it likely to collect dirt and require washing. And the Congressional Record shows that when the U.S. Senate took up the question of a redesign, its complaint was that the coins didn’t stack properly—a problem for bank tellers and merchants—rather than how Lady Liberty was, uh, stacked.

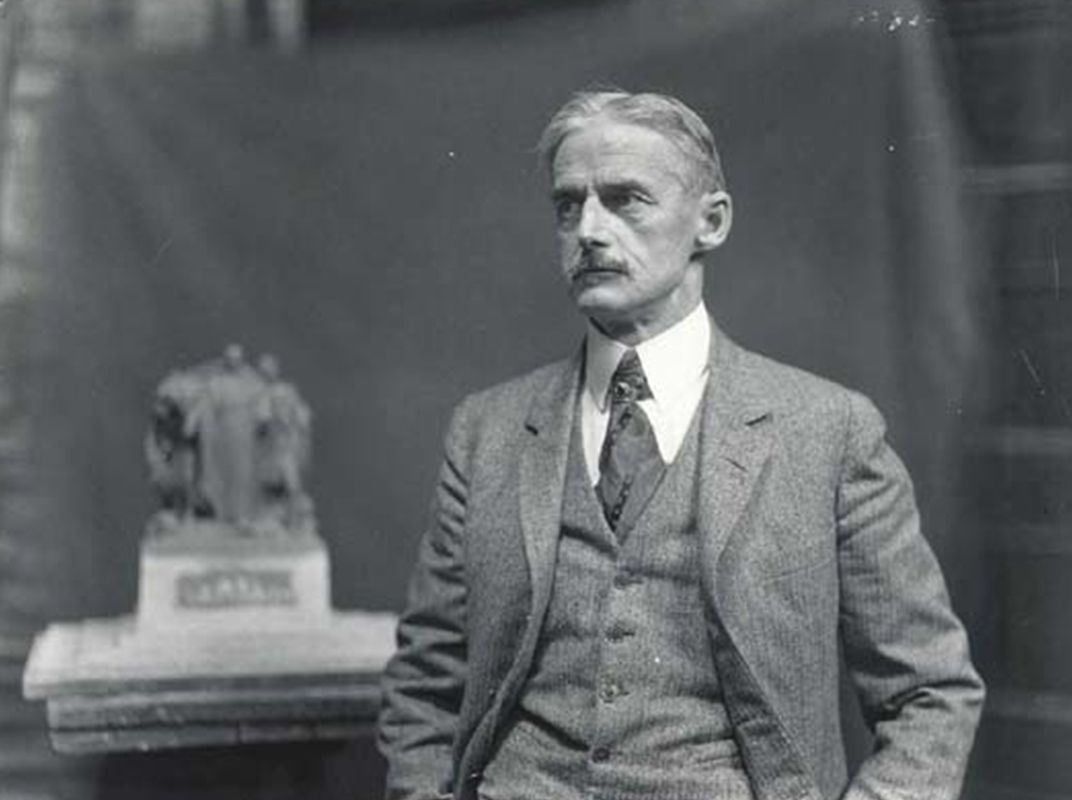

The coin’s designer, a respected sculptor named Hermon A. MacNeil, wasn’t happy with how it had come out, either. Given the opportunity to redesign the coin, he made a number of changes, just one of which was the addition of the chain mail. Liberty’s battle-ready look may have been a response to the First World War, which was raging in Europe and which the U.S. would officially join in April 1917, rather than a nod to modesty.

All of those factors—more than a priggish populace—seem to have doomed the 1916 design.

Though much of the myth has now been toned down, it still has legs. The decades of fuss—some of it real, much of it exaggerated—seem to have guaranteed the 1916 coin a lasting place among collector favorites.

Today even a badly worn specimen can command a retail price of over $4,000, compared with about $35 for the more-chaste 1917 coin in the same condition. A mint condition quarter could be worth as much as $36,500.

The low production volume of the 1916 coins accounts for some of that price, but hardly all of it. Even in the sedate world of coin collecting, usually not considered the sexiest of hobbies, there’s nothing like a little scandal to keep a legend alive.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/greg2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/greg2.png)