The Igorrote Tribe Traveled the World for Show And Made These Two Men Rich

Truman Hunt and Richard Schneidewind were locked in a fierce competition, but by the end, the tribespeople were left poor, hungry and yearning for home

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/13/b8/13b827be-1d5b-44b9-951c-fa6b62e6a462/the_igorrotes_on_show_at_coney_island_summer_1905_.jpg)

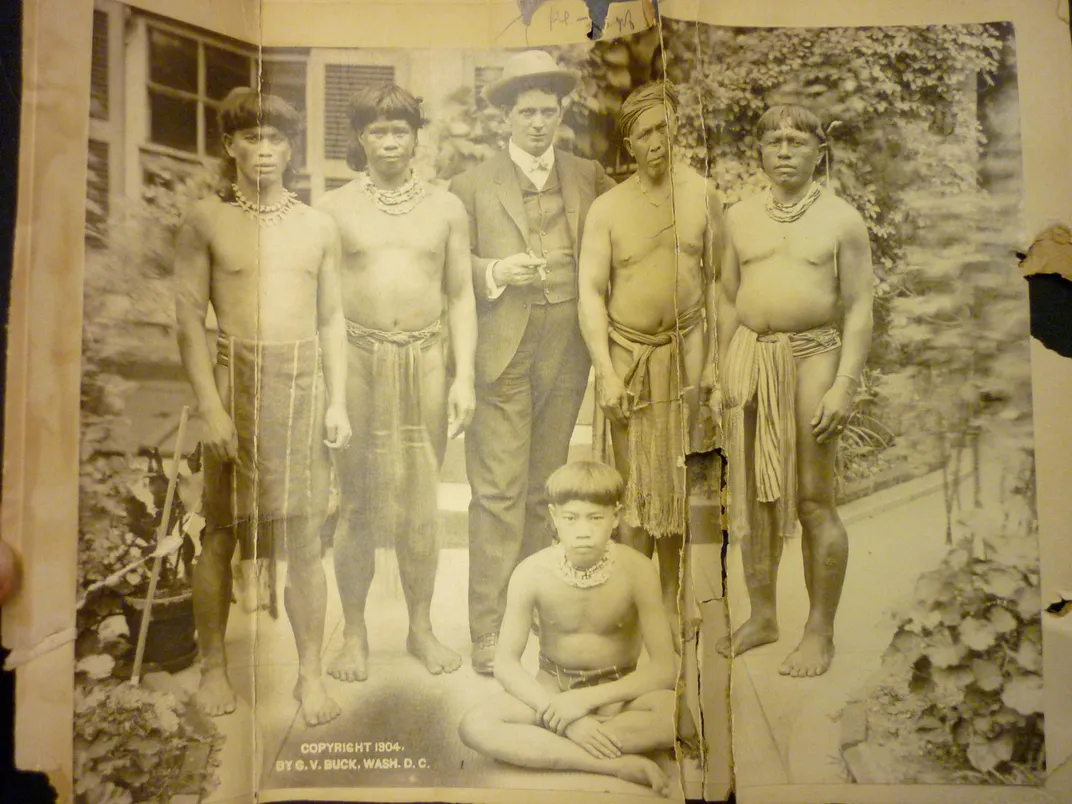

A group of tribespeople danced with jerky movements as a man, barefoot and wearing only a g-string, dragged a dog by a rope. The mutt snapped and snarled. Then with one deft stroke, the man slit the animal’s throat before chopping its lifeless body into pieces and throwing it into a pot. This was the Igorrote Village at Coney Island, and in 1905, it was the talk of America.

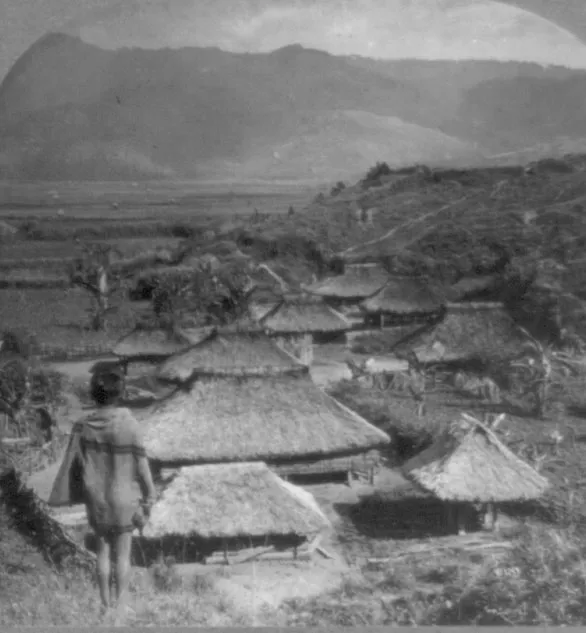

The Igorrotes, or Bontoc Igorrotes to use their full tribal name, were from a remote region in the far north of the Philippines named Bontoc. Truman Hunt, an opportunistic former medical doctor turned showman, came up with the idea of transporting 50 Igorrotes to America and putting them on display in a mocked-up tribal village at Coney Island.

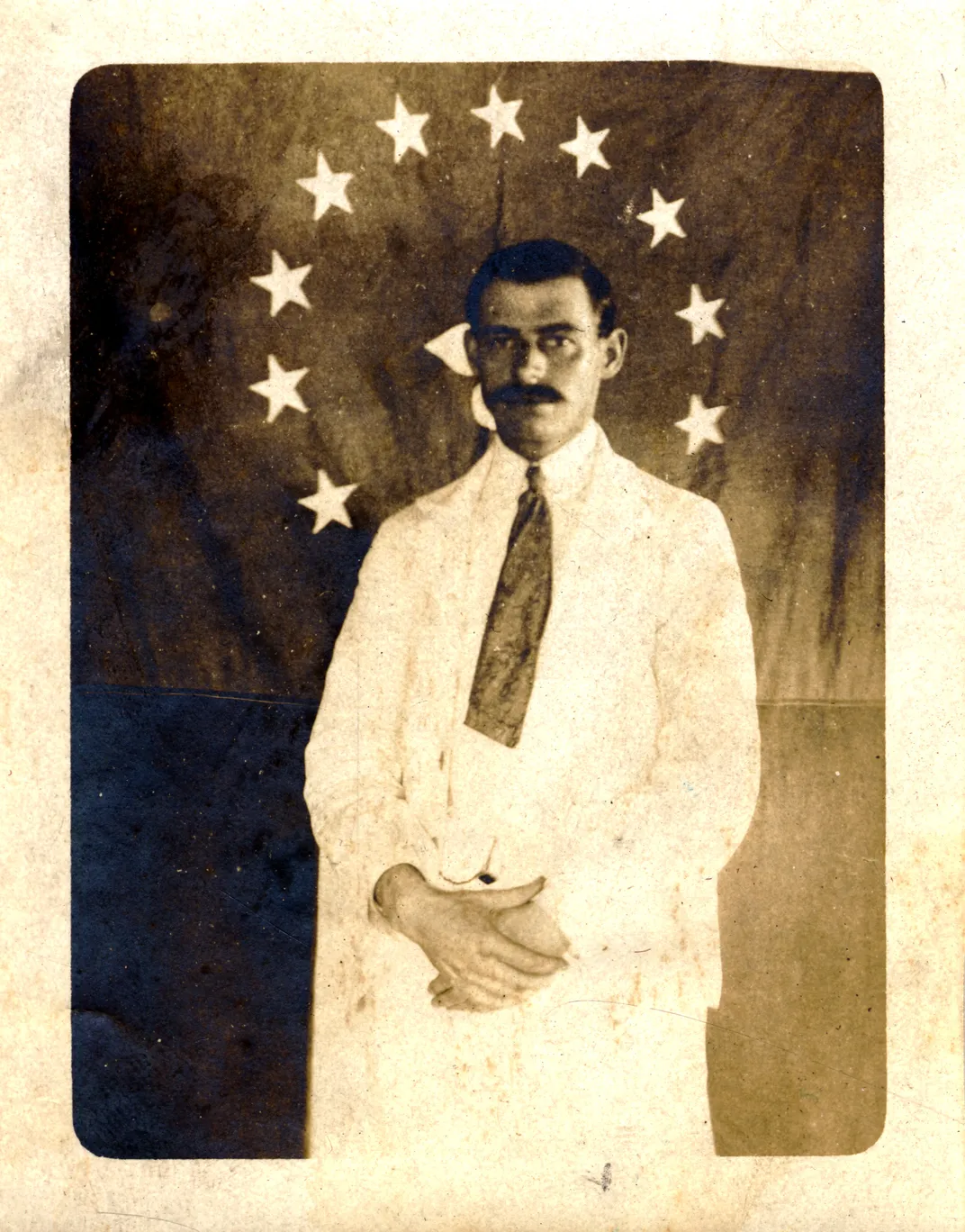

Hunt was a Spanish-American War veteran and former lieutenant governor of Bontoc, where he had become a trusted friend of the Igorrotes. The United States took control of the Philippines from Spain as part of the terms of the 1898 Treaty of Paris ending the war between the two nations. The U.S. also received stewardship of Puerto Rico and Guam and ceded its claim to Cuba. In the following years, however, Filipino nationalists uninterested in becoming the subjects of yet another colonial power, fought a prolonged three-year war with the United States, leading to the deaths of 4,200 Americans and casualties on the Filipino side that numbered in the hundreds of thousands, including combatants and civilians.

The assumption of American control over the overseas territory prompted deep soul-searching at home. Was it right for America to acquire an overseas empire? When, if ever, would the Filipinos be ready to take over the responsibility of governing themselves? Faced with growing public opposition at home, the U.S. launched a pacification process lead by future president William Howard Taft that provided for Filipino self-governance and eventual independence.

In early 1905, Truman Hunt traveled to Bontoc and made the Bontoc Igorrotes an audacious offer: if they agreed to leave their family and friends behind for a year and journey with him to United States to put on a show of their native customs, he would pay them each $15 a month in wages.

At Coney Island, the Igorrotes performed a distorted version of their tribal rituals. They sang and danced, they held sham weddings and dog feasts with mutts brought from the pound.

They were visited by millions of ordinary Americans, along with anthropologists, linguists, famous singers and actors, and even Alice Roosevelt, President Theodore Roosevelt’s daughter. The tribesmen, women and children inspired poems, newspaper cartoons, advertising slogans and jigsaw puzzles, and were written about in the New York Times, the Washington Post and by the Associated Press.

Before long, the Igorrotes had made Hunt a fortune.

But he was spending money as quickly as the Igorrotes earned it. He had no desire to share his lucrative trade with anyone. But, hot on Hunt’s heels, another group of Igorrotes arrived in America. They were traveling with Richard Schneidewind, another Spanish-American war veteran and a former cigar salesman.

The two men could not have been more different. Hunt was a charming risk-taker, and came to regard the tribespeople as a commodity. Schneidewind, who had been married to a Philippine woman who died giving birth to their first son, treated “his” tribespeople like family. He invited them to his home to meet his son and to eat dinner with them.

Schneidewind took his Igorrote exhibition group to the 1905 Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon, then on to Chutes Park in Los Angeles, where they were a huge hit.

Hunt was furious. He split his tribespeople in to several troupes to maximize his profits. Hunt’s groups toured the country, making dozens of stops, lasting anything from a few days to several weeks.

The rivalry between Hunt and Schneidewind was intense. In May, 1906, Hunt and Schneidewind ended up at competing parks in Chicago. There the two showmen did everything they could to undermine each other’s exhibits.

Hunt rubbished Schneidewind’s reputation to his newspaper friends. Schneidewind and his business partner, Edmund Felder, wrote to the head of the Bureau of Insular Affairs, the U.S. government agency located within that War Department charged with administering the nation’s newly acquired territories. Their letter reported that the village operated by Hunt and his associates at Sans Souci Park in Chicago was in a terrible condition. The 18 men and women in Hunt’s group, they wrote, were crammed into three small A-frame tents in a muddy scrap of land beneath the roller coaster. Their description, though arguably motivated more by business rivalry than concern for their fellow human beings, was accurate.

A member of the public -- possibly put up to it by Schneidewind and Felder -- wrote to the Bureau complaining that the Bontoc Igorrotes were living in squalor. There were further rumors that Hunt had stolen the tribe’s wages and that two men in the group had died on the road and that the showman had failed to have their bodies buried.

Both Hunt and Schneidewind had brought their Igorrote groups into America with permission from the U.S. government, an entity with a clear incentive to portray the people of the Philippines as primitive. How could such a society govern itself if it was filled with citizens as “backwards” as the Igorrotes? If it was true that Hunt was mistreating the Igorrotes, the government could hardly afford to be engulfed in a major scandal that could turn public opinion even further against a permanent presence in the Philippines.

Alarmed, the chief of the Bureau of Insular Affairs, Clarence Edwards, and his deputy, Frank McIntyre, called in one of their agents, Frederick Barker, and asked him to investigate the claims.

When Hunt received a tip-off that the Bureau was sending a man to examine his Igorrote enterprise, he fled town. He went on the run, taking some of the tribespeople with him.

A manhunt followed as Pinkerton detectives, the government agent, creditors and a woman who accused Hunt of bigamy pursued the showman across America and Canada. Hunt proved himself to be a slippery opponent. Finally, in October 1906, he was arrested on multiple charges of stealing from the Igorrotes and sentenced for 18 months in the workhouse after a sensational trial in Memphis.

With his rival out of the way, Schneidewind emerged as the leading showman in the Igorrote exhibition trade. In the winter of 1906, Schneidewind returned to the Philippines to collect another Igorrote group and embarked on a second tour of America. A third U.S. tour followed in 1908.

In 1911, despite vociferous opposition from Bontoc tribal elders and officials of nearby towns, Schneidewind was permitted to take a group of 55 Igorrotes to Europe, where they exhibited in France, Scotland, England, the Netherlands and Belgium.

Schneidewind and his associates were unfamiliar with the European entertainment business, and in 1913, after two years on the road, they ran into serious financial difficulties. What happened next was alarmingly reminiscent of Truman Hunt’s tour. According to American newspaper reports, in the winter of 1913 a group of starving Igorrotes was found wandering the streets of Ghent, Belgium. The group’s interpreters, Ellis Tongai and James Amok, wrote to President Woodrow Wilson begging for his assistance. In their letter, they complained that they had not been paid for many months and reported the deaths of nine members of their group, including five children.

Schneidewind told the Igorrotes that if they stayed on and continued working for him until the 1915 San Francisco Exposition then they would earn a handsome wage, allowing them to return home rich. Despite the hardships they had endured, about half of the group wished to stay on in Europe, a sign perhaps that Schneidewind’s troubles owed more to incompetence than to cruelty or a lack of compassion for the Filipinos.

But, fearing another scandal, the U.S. government was unwilling to give Schneidewind another chance and decided they must intervene. In December, 1913, the U.S. consul in Ghent escorted the tribespeople to Marseilles to catch a boat back to Manila.

This disastrous venture did little to help the image of the Igorrote show trade. The Philippine Assembly took action and, in 1914, passed legislation that banned the exhibition of groups of Filipino tribespeople abroad. As a measure of the seriousness with which the Philippine lawmakers regarded the subject, the ban was included as an amendment to a new Anti-Slavery Act.

Schneidewind, like Truman before him, exited the Igorrote show trade. For a full decade, starting in 1905, the Igorrotes had been the greatest show in town, thrilling and scandalizing the American public, and filling the nation’s newspapers. But in the intervening period, they disappeared from the public consciousness.

One of the few extant public acknowledgements of the Igorrote show is in Ghent, where an initiative to commemorate the city’s World Exhibition of 1913 lead to the naming of streets and tunnels after notable participants of this historical event, including Timicheg, one of the nine Igorrotes who died on Schneidewind’s European tour. The Philippine Ambassador to Belgium remarked at the time that it was "commendable that the City of Ghent has not only chosen to celebrate the achievements relating to the 1913 expo, but has been able to balance this by commemorating those who experienced difficulties to participate in this event".

More than a century on, the time has come to tell the Igorrote's incredible story.

For more information on The Lost Tribe of Coney Island, visit claireprentice.org