How a KGB Spy Defected and Became a U.S. Citizen

Jack Barsky wanted to stay in the country, so he let the Soviets think he was dead

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3c/cf/3ccf427a-dcf5-4b50-be2f-28197090e352/albrecht-der-student.jpg)

Jack Barsky was standing on a New York subway platform in 1988 when someone whispered in his ear: “You must come home or else you are dead.” No one had to tell him who’d sent the message. For ten years, Barsky had been a Soviet spy in the United States. Now, the KGB was calling him back. But Barsky wanted to stay.

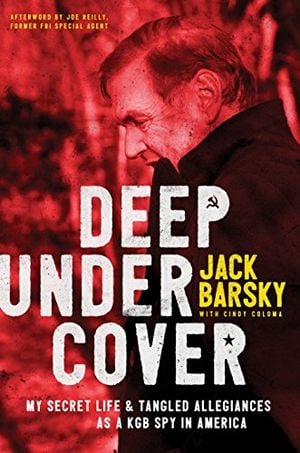

Amazingly, he did—and lived to tell the tale. In his new book, Deep Undercover, he tells the incredible story of how he adopted a false identity, misled the KGB into assuming he was dead and later cooperated with the FBI. But the most dangerous part of his career wasn’t his undercover work. Rather, it was defying the KGB when the agency ordered him to leave.

Barsky was born as Albrecht Dittrich in East Germany in 1949. When the KGB approached him in his early 20s, he had a positive view of Communists—they were the Nazi-fighting good guys.

“I was ideologically fully convinced that we were on the right side of history,” he says.

And so, in 1979, he began his new life as an undercover KGB spy in the U.S., gathering information for what he believed was a worthy cause. He went by the alias Jack Barsky, a name taken from a real American boy who had died at a young age and whose birth certificate Barsky used to pass as an American citizen. Within a few years, he started working at MetLife Insurance in New York City. (“The insurance companies, for some reason, were singled out as the epitome of evil in capitalism,” he says.)

Barsky’s assignments weren’t exactly like those on TV’s “The Americans” (though he will appear in an episode of the show on May 9). Some of his tasks included identifying people who might be good KGB recruits, filing reports about Americans’ reactions to current events, and transferring U.S. computer programs to the Soviets.

He kept this espionage hidden from his American friends and the woman he married in New York. Ironically, his wife was an undocumented immigrant from Guyana, and it was his fabricated citizenship that allowed her to stay in the country.

Barsky continued this double life until 1988, when the KGB sent him a radio message saying that his cover may have been compromised and he needed to return home. He didn’t know why they suspected this—and he never learned the answer. When he ignored the KGB’s first radio message, they sent another one. And when he ignored that, too, his bosses took more drastic measures.

“They knew the footpath that I used to get to the subway station, and there was a spot that I described to them where they could put signals,” he says. If Barksy saw a red dot placed in that spot, he’d know the KGB wanted to convey an emergency signal. Soon after the initial radio messages, Barsky saw that red dot on his way to work.

“It was an order: Get out of here. No questions asked,” he says. The signal didn’t just mean he should leave soon, it meant he should retrieve his emergency documents—which he’d stashed somewhere in the Bronx—and head to Canada immediately.

“But I didn’t do what the dot ordered me to do,” he says. Why? Because “unbeknownst to the folks in Moscow, I had a daughter here who was 18 months old.”

Even though he had another wife and a son in Germany, Barsky didn’t want to leave his new baby in the U.S. One week after he saw the dot, he received the KGB’s whispered death threat on the subway platform. If he wanted to stay, he says, he’d have to do something “to make sure that they wouldn’t come after me or possibly even do harm to my German family.”

Finally, Barsky sent a gutsy response to the KGB. He told them that he had AIDS and needed to stay in the U.S. to receive treatment. The agency should transfer his savings to his German wife, he told them. And that was it.

“For about three months [after the lie], I varied the way I went to the subway,” he says. “I would go to work at different times and I would zigzag differently, just in case somebody wanted to look for me and do something bad. And after that, when nothing happened after three months, I thought I was in the clear.”

He was right. The KGB assumed, as Barsky had hoped they would, that if he had AIDS, death was imminent. Years later, Barsky learned that when the KGB gave his savings to his German wife, they indeed told her that he died of AIDS-related causes.

After that, Barsky lived a pretty normal life. He continued to work at MetLife and then United Healthcare, bought a house, and had another child with his Guyanese American wife. Things might have continued on this way if the FBI hadn’t received a tip about him in the 1990s. After some initial surveillance, they bugged his house and ended up overhearing the moment when Barsky finally revealed his KGB past to his wife. (That marriage also didn’t last.)

Barsky has since provided information about the KGB to the FBI, married a third time, and become a U.S. citizen. His legal name is still the alias that he stole from that young boy’s birth certificate. When asked if he also still celebrates the birthday on Barsky’s birth certificate, he replied, “I don’t celebrate anything. I’m too old.”

Whether that’s true is up for debate. But his evasive answer underlines what might be the most interesting part of his story—that at some point, the KGB spy turned into the American he was pretending to be.