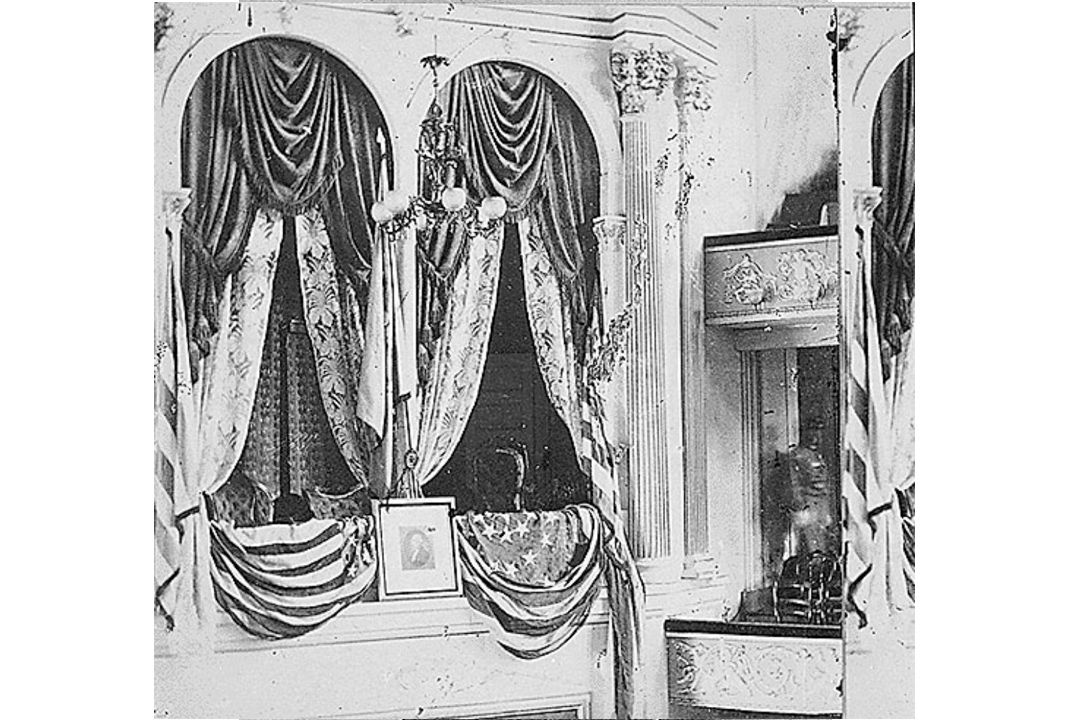

An Assassin’s Final Hours

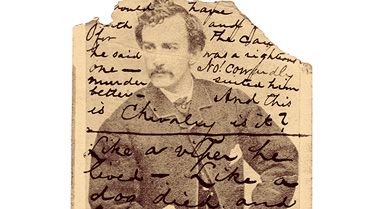

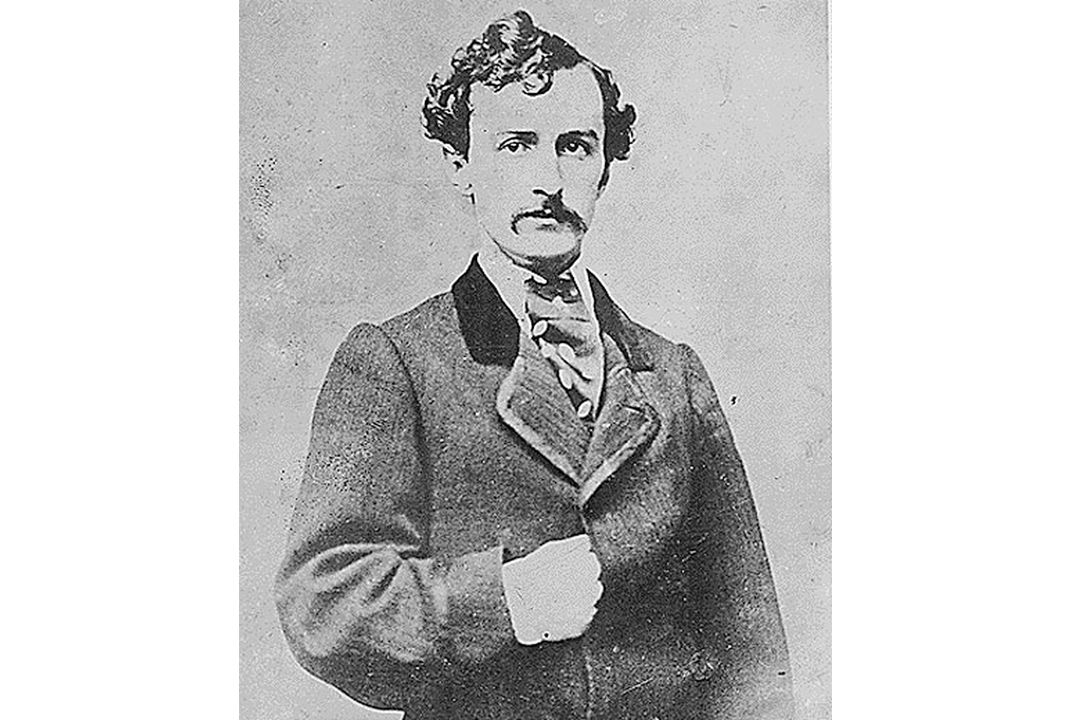

John Wilkes Booth, cornered in a Virginia barn, wanted to go down fighting: “I have too great a soul to die like a criminal”

The dogs heard it first.

Rising from the southwest. Distant sounds, yet inaudible to human ears, of metal touching metal; of a hundred hoofs sending vibrations through the earth; of labored breathing from tired horses; of faint human voices. These early warning signs alerted the dogs sleeping under the Garretts’ front porch. At the farm, John Garrett, corn-house sentinel, was already awake and the first to hear their approach. William Garrett, lying on a blanket a few feet from his brother, heard them too.

It was after midnight, and dark and still inside the farmhouse. Old Richard Garrett and the rest of his family had gone to bed hours ago.

All was quiet, too, in the tobacco barn, where John Wilkes Booth and David Herold, another conspirator in the plot to kill Abraham Lincoln, were sleeping. The barking dogs and the clanking, rumbling sound finally woke Booth. Recognizing the unique music of cavalry on the move, the assassin knew he had only a minute or two to react.

Abstract taken from Manhunt: the 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer, by James L. Swanson, an excerpt of which appeared in the June 2006 issue of SMITHSONIAN. All rights reserved.