NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

These are the Decade’s Biggest Discoveries in Human Evolution

Celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Smithsonian’s “David H. Koch Hall of Human Origins” with some of the biggest discoveries in human evolution from the last 10 years.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Three_early_human_skulls_on_a_dark_background.jpg)

Human evolution is one of the most vibrant areas of scientific investigation. In the past decade we’ve seen many discoveries that add to our understanding of our origins. To mark the 10th anniversary of the Smithsonian’s “David H. Koch Hall of Human Origins,” here are some of the biggest discoveries in human evolution from the last 10 years.

We have ancient DNA

DNA tells us a lot about who we are now. But we also look to ancient DNA to learn about our origins.

When the decade first started, scientists recovered ancient genetic material from a fossilized finger bone found in the Denisova Cave in Siberia. They tested that material and discovered that the DNA didn’t match that of modern humans or Neanderthals. Instead, it belonged to a previously undiscovered species of early humans now called Denisovans. It was the first time a new species has been identified using ancient DNA.

What does this tell us? The human genome is a wondrous archive of our relationships with ancient species no longer around.

Meet our new ancestors

Over the past decade, we welcomed four new species to our family tree, including the mysterious Homo naledi.

In 2015, scientists announced the discovery of fossils of at least 15 individuals of this species in a deep, dark chamber of the Rising Star Cave system in South Africa. It's five years later and we still aren’t sure how they got there. There’s no evidence they were dragged there by predators or washed in by water. And no other animal bones were found in the cave except for the bones of a single owl. Were the bodies placed there deliberately? If so, by whom? It’s a mystery still to be solved.

What we do know is that the remains are from 335,000-236,000 years ago and show a unique mix of ancient and human traits, making Homo naledi one of several species that overlapped in time with our own.

Fossil discoveries tell more of our story

Not all fossil discoveries lead to a new species. But new fossils always reveal more of our story.

In the past ten years, we’ve found fossils that widen both the geographic and time range of several early human species. But one of the most exciting discoveries is of a nearly complete 3.8-million-year-old cranium of Australopithecus anamensis from Woronso-Mille, Ethiopia. Until this find was announced in 2019, researchers had only found bits and pieces of this species from various sites across Ethiopia and Kenya.

Fossils older than 3.5 million years are extremely rare. But what makes this discovery particularly amazing is that it challenges the previous assumption that A. anamensis was the direct ancestor of the species Australopithecus afarensis—to which the famous fossil “Lucy” belongs. Thanks to this skull, we now know that the two species overlapped in time.

We made tools earlier than we thought

When you think of technology today, you might picture computers, smartphones, and gaming consoles. But for our ancestors millions of years ago, it would have been stone tools.

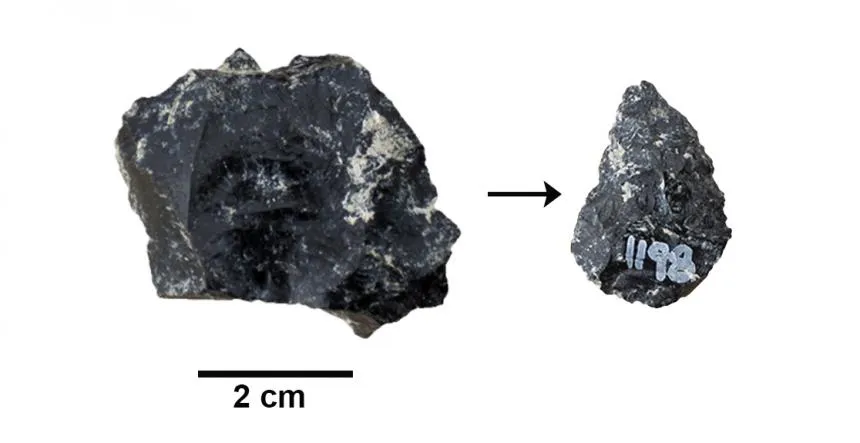

We long thought our ancestors began making these tools about 2.6 million years ago. But a discovery announced in 2015 pushed that date back. The research team found pieces of altered stone in Lomekwi, Kenya, that date to 3.3 million years ago. These stones are larger and simpler than those that were previously thought to be the oldest stone tools.

The new discovery suggests that the ability to flake stone tools arose at least 700,000 years before it became a regular habit in the lives of our ancestors.

We’re older than we thought

Stone tools aren’t the only things that are older than we thought. Humans are too.

Just three years ago, a team of scientists made a discovery that pushed back the origin of our species, Homo sapiens. The team re-excavated a cave in Morocco where a group of miners found skulls in 1961. They collected sediments and more fossils to help them identify and date the remains. Using CT scans, the scientists confirmed that the remains belonged to our species. They also used modern dating techniques on the remains. To their surprise, the remains dated to about 300,000 years ago, which means that our species originated 100,000 years earlier than we thought.

Social Networking Isn’t New

With platforms like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, it hard to imagine social networking being old. But it is. And, now, it’s even older than we thought.

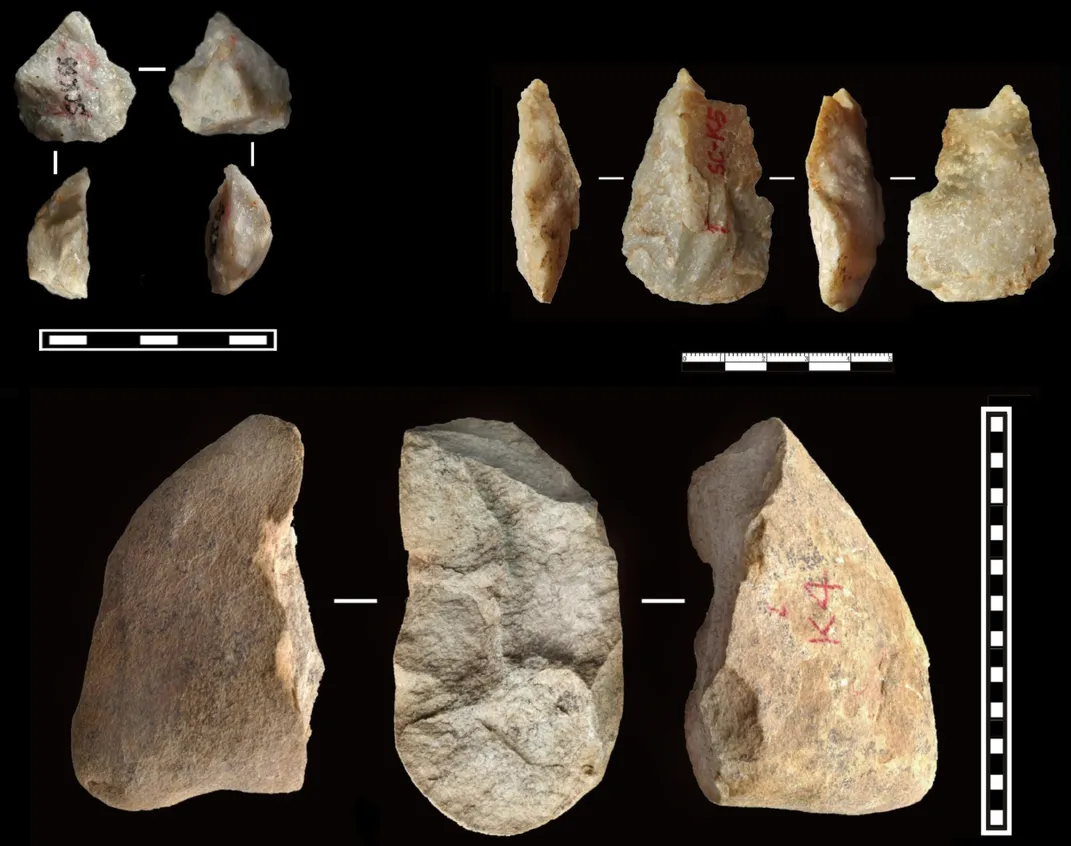

In 2018, scientists discovered that social networks were used to trade obsidian, valuable for its sharp edges, by around 300,000 years ago. After excavating and analyzing stone tools from southern Kenya, the team found that the stones chemically matched to obsidian sources in multiple directions of up to 55 miles away. The findings show how early humans related to and kept track of a larger social world.

We left Africa earlier than we thought

We’ve long known that early humans migrated from Africa not once but at least twice. But we didn’t know just how early those migrations happened.

We thought Homo erectus spread beyond Africa as far as eastern Asia by about 1.7 million years ago. But, in 2018, scientists dated new stone tools and fossils from China to about 2.1 million years ago, pushing the Homo erectus migration to Asia back by 400,000 years.

Also in 2018, researchers announced the discovery of an upper jaw in Israel that looked like that of our own species, Homo sapiens. The jaw ended up being 174,000-185,000 years old. This discovery—along with others from China and Greece—suggest that Homo sapiens wandered short-term into Eurasia well before the worldwide migration that began 70,000 years ago.