NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

Pride Month 2020: Perspectives on LGBTQ Native Americans in Traditional Culture

For Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Pride Month, Dennis Zotigh, a cultural specialist at the National Museum of the American Indian, invited Native friends to tell us how their traditional culture saw its LGBTQ members. A Chiricahua Apache friend replied, “Now, Dennis, this is a human question, not [just] Native.” We agree. But we also appreciate hearing what Native Americans have learned, reconstructed, or been unable to reconstruct about this part of our shared history and experience.

:focal(754x123:755x124)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Adrian_Stevens_and_Sean_Snyder_1500-750.png)

June is Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Pride Month in the United States. As part of our observance this year, the National Museum of the American Indian invited Native friends to share what they understand about how LGBTQ people were regarded in their traditional culture.

Native nations are similar to other world populations in the demographic representation of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals. Many tribal languages include specific vocabulary to refer to gender identities beyond male and female; others do not, or those terms have been lost. Similarly, there are many differences in how Indigenous communities and tribes saw or responded to gender variance. In some tribes and First Nations, stories are passed down of individuals who had special standing because they were LGBTQ. Their status among their people came from their dreams, visions, and accomplishments that revealed them as healers and societal or ceremonial leaders. In other tribes, LGBTQ people had no special status and were ridiculed. And in still other tribes, they were accepted and lived as equals in day-to-day life.

European contact, conquest, and expansion disrupted the community and ceremonial roles of LGBTQ Natives, along with other cultural traditions, and imposed new values through Christian religion and non-Native institutions, policies, and laws, such as boarding schools and relocation. Under federal authority, traditions of all sorts were forbidden, condemned, or punished, including through violence, and much traditional knowledge was lost.

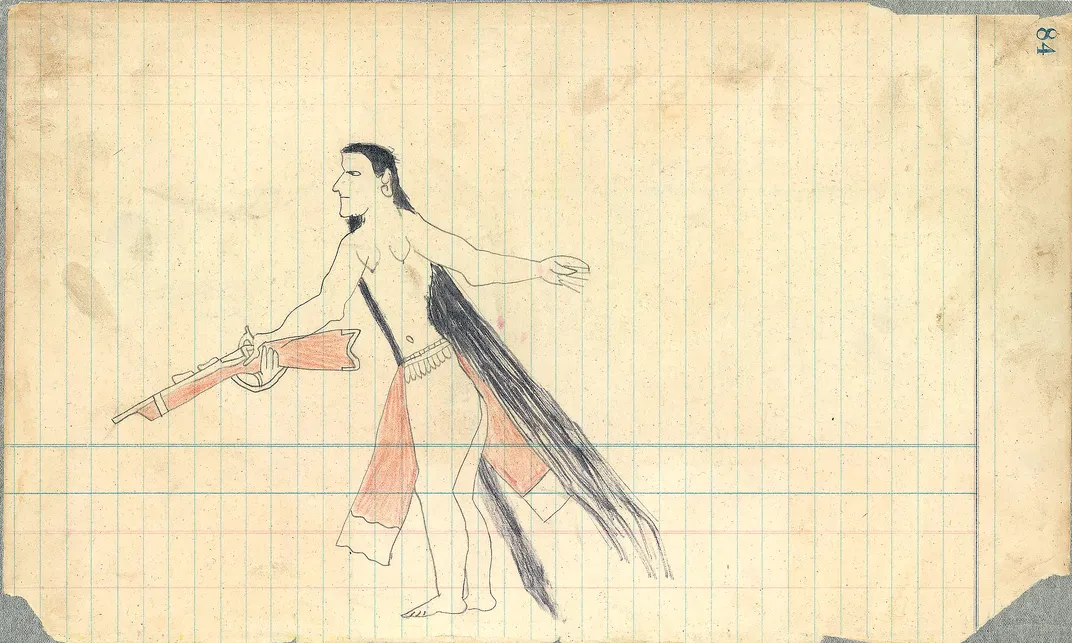

The term Two Spirit derives from niizh manidoowag (two spirits) in the Anishinaabe language. Adopted as part of the modern pan-Indian vocabulary in 1990 during the third annual inter-tribal Native American/First Nations Gay and Lesbian American Conference, in Winnipeg, Manitoba, it refers to individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, transgender, transsexual, or gender-fluid. At the same time, many tribal members prefer to use words for gender variance from their own people’s language. The National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) gives dozens of examples, including winkte/winkta (Lakota/Dakota), badé (Crow), mixoge(Osage), and nàdleehé (Diné).

While some Two Spirits face discrimination, obstacles, and disparities, others feel comfortable to blend in with the fabric of contemporary society. NCAI research lists 24 tribes whose laws recognize same-sex marriage. Native people are becoming increasingly liberated and proud of their Two Spirit roles and traditions. Native LGBTQ and their allies host tribal pride festivals, powwows, conferences, and seminars, as well as participating in national awareness events, conventions, and parades. In many Native nations and tribes, LGBTQ members again serve traditional roles in ceremonial life.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, Native Two Spirits—like other LGBTQ communities, including the Smithsonian Pride Alliance—have taken to the Internet to celebrate Pride 2020. Two Spirit individuals are sharing their stories and journeys on social media under the hashtag #IndigenousPrideMonth.

For our pride observance this year, the museum asked our Native friends, “How did your tribe traditionally view individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender?”

A Chiricahua Apache friend replied, “Now, Dennis, this is a human question, not [just] Native.” I agree! But I also want to know what people have learned, reconstructed, or been unable to reconstruct about this part of our shared history. Their answers are identified by the writer’s Native nation:

Nipmuc: This is a complex question. Unfortunately, due to colonial genocide on the East Coast, much of this history was quickly hidden, forbidden to talk about, especially under the zealous Christianity of the time. In my Nipmuc Algonquin people, I was taught that the people of same-sex relationships were revered, had a dualistic connection with land and spirit, and hence were viewed as having a sort of mana or spiritual power.

We are a matrilineal society. So feminine energy had an equal if not more profound agency within the social stratification. Marriages were nothing like you would see in Europe at the time. Women were free to marry who they wished and leave who they wished without repercussion. . . . Nipmucs were not perturbed about sex or the human body. . . . When you remove the fear of sex and the human body, and women are not treated like property, the entire concept of two people showing and sharing love completely changes. . . .

Crow: Osh-Tisch, also known as Finds Them and Kills Them, was a Crow badé (Two Spirit) and was celebrated among his tribe for his bravery when he attacked a Lakota war party and saved a fellow tribesman in the Battle of the Rosebud on June 17, 1876. In 1982, Crow elders told ethnohistorian Walter Williams, “The badé were a respected social group among the Crow. They spent their time with the women or among themselves, setting up their tipis in a separate area of the village. They called each other ‘sister’ and saw Osh-Tisch as their leader.”

The elders also told the story of former Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) agents who tried repeatedly to force Osh-Tisch to wear men’s clothing, but the other Indians protested against this, saying it was against his nature. Joe Medicine Crow told Williams: “One agent in the late 1890s . . . tried to interfere with Osh-Tisch, who was the most respected badé. The agent incarcerated the badés, cut off their hair, made them wear men’s clothing. He forced them to do manual labor, planting these trees that you see here on the BIA grounds. The people were so upset with this that Chief Pretty Eagle came into Crow Agency and told the agent to leave the reservation. It was a tragedy, trying to change them.”

Osage: We called them mixoge, which means “follows the teachings of the moon.” The moon was said to be our grandmother. They were just viewed as people, like everyone else.

Acoma and Laguna Pueblo: They were seen as medicine, because they were a balance of the feminine and masculine. My parents said there was no mocking or ostracizing in our stories. These actions came with the church infiltrating our culture. When our people began to move off tribal areas, outside influence took over traditional teachings. My grandmother, the late Lucy Lewis, had gay and lesbian friends. She never saw them by their sexual preference. She saw them as a friend. It is something my mom and dad have taught us and that [my husband] and I teach our children.

Shoshone–Bannock: Historically and culturally among my people, when men had a female spirit, they stayed behind from a war or hunting party and helped the women and elders. The Two Spirit man who chose to follow his female spirit had the strength or muscles for lifting and carrying heavy items. According to the elder women, who shared this history, they were greatly appreciated. You have to remember at first boys and girls were raised and nurtured according to gender. They were taught skills to assist the people.

Women who had a male spirit were helpful to war parties, too. They knew how to cook, repair, etcetera. They had extra knowledge. Some of our Two Spirit people also became medicine people, because they understood the nature of two sides. They had this extra knowledge.

They were natural members of Creator’s creation and had a purpose like any other human being. This is what was shared with me as I traveled and spent time with twelve elders. It was when white religious values and assimilation were imposed on the people that certain views were impacted for a time, although the traditional members of our people were still accepting through this period. And today our Two Spirit people are accepted and a natural part of our cultural society: “They are human beings with extra knowledge and an extra spirit.”

Diné: They are revered as holy beings. In our creation story, there is a time when the separation of sexes occurred. From that time, transgendered were referred to as naa'dłeeh (men) and dił'bah (women). And in that creation story they saved the people.

Northern Cheyenne: I was told never to tease or pick on them, to protect them because they were holy and were born with strong medicine. We have had Two Spirit painters and ceremonial leaders run our ceremonies as recently as a few years ago.

Kiowa: They were sort of like outcasts if they were out of the closet, and they had to live in the far outer parts of the camp and not with the rest of the people. Otherwise if they could hide it, they would be just like anyone else. They used to say ,“A onya daw,” meaning, “They are different from the rest of us.”

Southern Ute: As a consultant speaking with tribes and knowing my tribe, our views are different. Some tribes view the people as special. My tribe accepted them as different with no special powers. Some families believe if a man abused a woman long ago, Creator punished him by bringing him as an opposite sex. Bottom line, we just accept them as people.

Lakota: Winkte, yep—it’s the commonly accepted term for LGBTQ people, although some would say it’s more than just a sexual preference or a gender, but actually a societal and spiritual role in the Lakota traditional way of life. They were dreamers. They’d give Indian names, make people laugh, tease people. And they were often known for their artistic abilities. A lot of people forget the traditional roles they played, similarly to how people forget what it means to be a warrior in our culture as well.

Meskwaki: In Meskwaki culture, it is said that we have two souls. The good, small one, Menôkênâwa, and a larger one, Ketti-onôkênâwa. The smaller one was placed by the Creator, and that is our inner spirit. The larger one is outside our body and was placed there by Wîsakêa. He watches over our body after death. The larger one tends to become larger when a person innates himself with various traits such as anger, jealousy, etcetera. It seems he personifies anything that is the opposite of the Good Spirit in us. It is said that if he gets too big, he would even kill. These are the two spirits, as we see them. It has nothing to do with mainstream ideas and behaviors.

Coquille: I’m really not sure. There’s not a lot of recorded oral stories regarding this. There may be one or two mentions of a woman leading a war party. That sounded like a man and was thought to be a man by whites. But that really doesn’t adequately define her.

However, this: In 2008 the Coquille Indian Tribe passed a law recognizing same-sex marriage.

The Coquille are believed to be the first Native nation in the United States to legalize same-sex marriage.

We hope you have a meaningful Pride Month.