A New Exhibition Explores the Science and Math in Children’s Book Illustrations

The 29 artworks on display capture the wonder in nature, engineering and discoveries

Think back to a favorite picture book, the one where the edges of the cover grew worn and a few pages loosened from the binding after so many readings. Perhaps it was the unfolding story that enthralled a young you, perhaps the luminous illustrations. Most likely it was the view the book offered into a different world.

"Picture books are some of the first memories I have for looking at and understanding the world around me," says J.D. Talasek, the director of the Cultural Programs of the National Academy of Sciences. But one doesn't have to be a child to find delight and wonder in images from children's books. That's the premise behind a new exhibition, "Igniting the Imagination," which opened this week at the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) in Washington D.C.

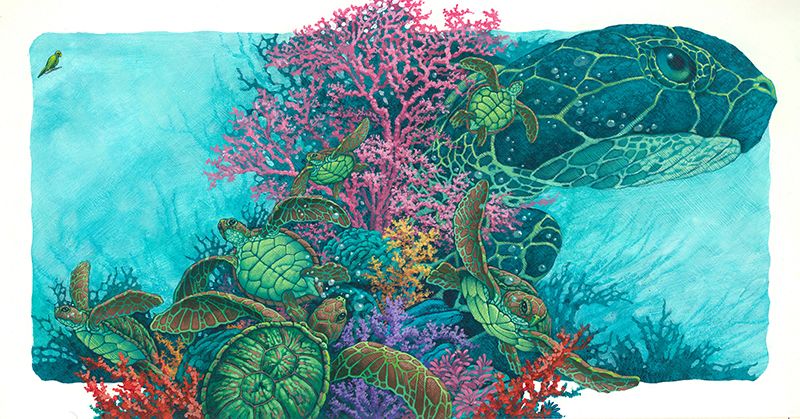

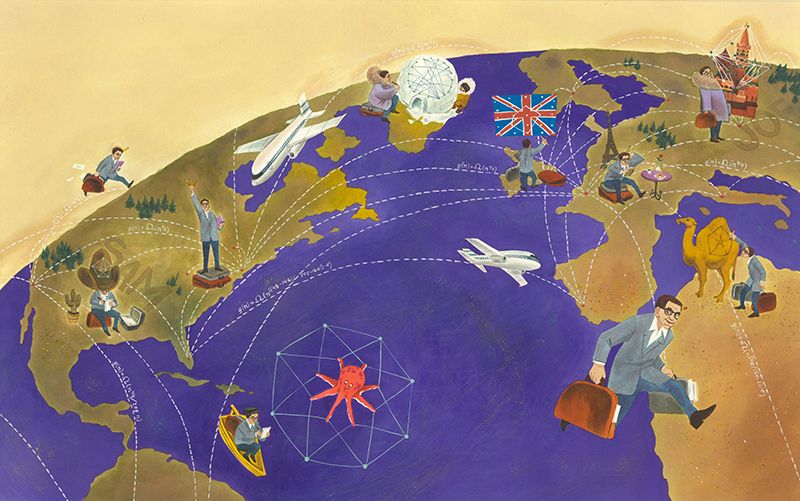

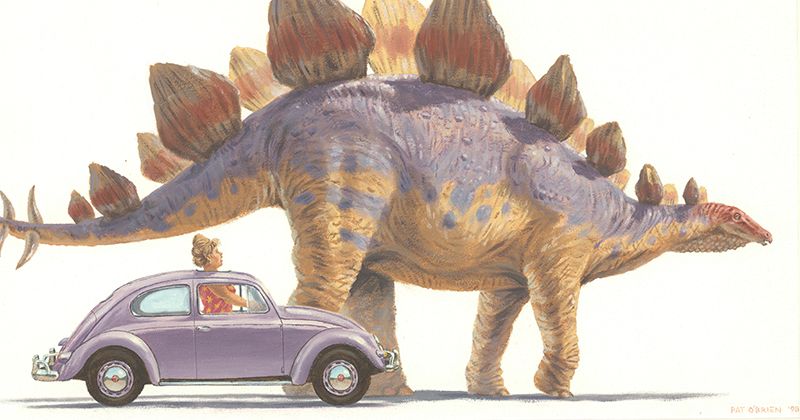

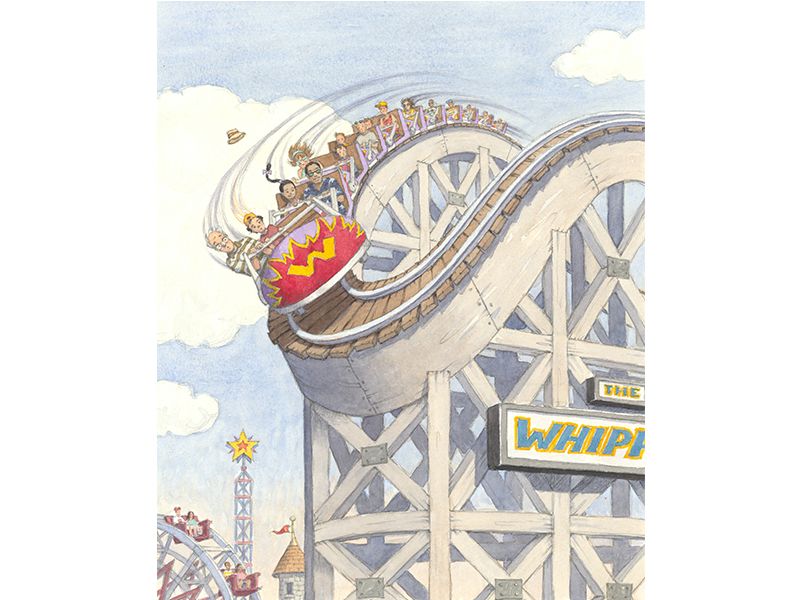

The exhibition features 29 artworks from the collection of children's book illustrations at the Mazza Museum, located at the University of Findlay in Ohio. Each illustration explores the worlds of science, engineering or medicine. In one, a bespectacled older gentleman and his companion, a young boy in a red t-shirt, lean to the side as they feel the centrifugal force of a rollercoaster's curve. The man's hat floats above and behind him, pushed off by the wind of his motion. In another, sea turtles appear to take off like a flock of sea-green-colored birds from a tower of pink, branching coral. A third juxtaposes the size of a Volkswagen Beetle driven by a poofy-haired woman with a stegosaurus sporting the same pale violet coloration as the vehicle.

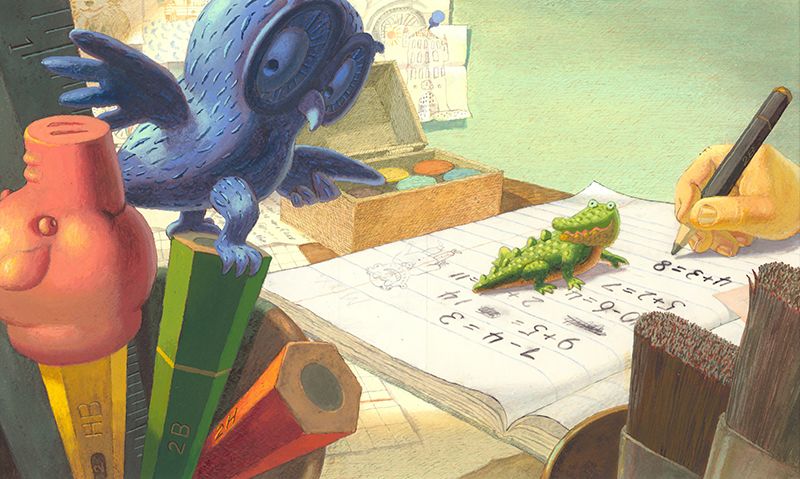

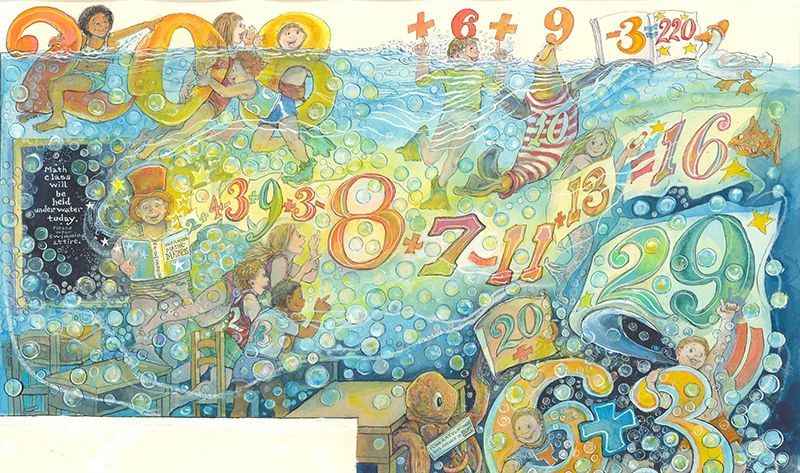

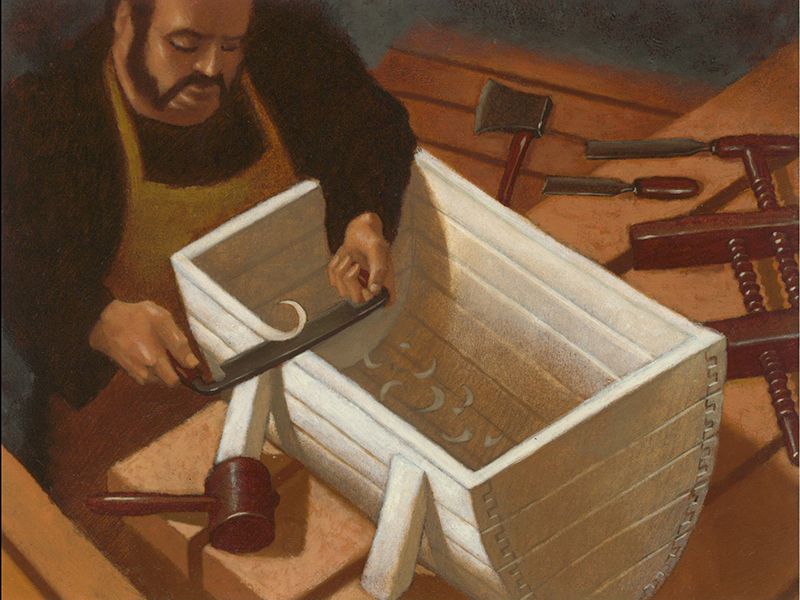

The illustrations come from books that span the past half-century: The oldest is from Project Boy by Lois Lenski, published in 1954, and shows a group of children building a fort out of "junk." The subjects traipse from the magic of math to the biology of a decaying log to the engineering of a skyscraper.

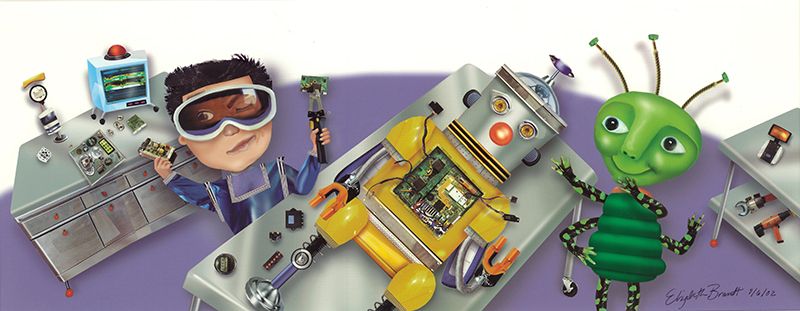

"The exhibit is framed through these disciplines, but it uses the power of art to help make broader connections to how inventions, practices and discoveries frame our experiences," Talasek says.

Each image was selected to grab the viewer's attention through color, composition or the presence of something unusual and unexpected. "There is a kind of preconceived notion that art from children's books is simple, but you will see that the technical skill is astounding," says Dan Chudzinski, the curator of the Mazza Museum. "They would be at home in any art gallery."

The museum's collection was born in 1982, as part of a celebration of the 100th anniversary of Findlay College, the university's predecessor institution. Jerry Mallett, a professor of education at the time, spearheaded the establishment of the children's book illustration collection. What began as four pieces then has grown to more than 10,500 now through donations and acquisitions. The artworks include a diversity of styles and media.

An image from the book City Beats, illustrated by Jeanette Canyon, shows three pigeons perched on a twisted metal cable, overlooking a construction site. A reader holding the book itself might marvel at the plumpness of the pigeons, the weighty thickness of the cable and the stylish pebbled appearance of the sky and cityscape background. In person, the illustration proves to be a three-dimensional relief sculpture molded out of polymer clay. The sculpture was photographed for the book.

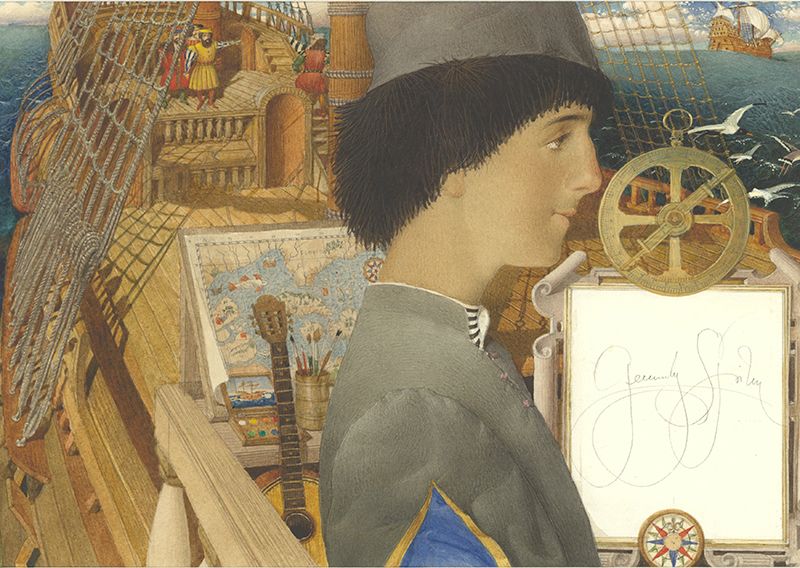

Other selections have similar surprises in store. Illustrator Robin Brickman crafted the ecosystem that springs up around a decaying log in A Log's Life from meticulously-cut pieces of paper. Gennady Spirin's scene of a cabin boy aboard a ship in To the Edge of the World, illustrated in a style reminiscent of a renaissance painting, is packed with details to reward the patient viewer—a map of the Gulf of Mexico replete with the approximations of early cartography and an old-style compass that Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan might have used.

"The whole point is to pique curiosity," Chudzinski says. "We want the art to be a catalyst to get someone to pick up the book and then learn science along the way." To aid that mission, copies of the books and comfy chairs for visitors to curl up in and read accompany the artworks on view at the NAS.

The exhibition sprang from an experience Jay Labov, the senior advisor for education and communication for the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine had as a visiting scholar to the University of Findlay.

Labov travels the country giving talks about STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) education. "One of the talks is about the importance of science as a liberal art in the 21st century," he says. "Too often we see, particularly in higher education, science being divorced from humanities." When he visited the Mazza Museum and gazed at paintings and drawings, the intricate design of a fold-out book caught his eye. A placard explained that engineers had helped design the pop-up constructions.

"It occurred to me that the illustrations in children's books were showing us interesting ways to understand science," he says.

"I know Jay has the heart of a child, playfulness and curiosity," Talasek says. "But he also just had a grandchild at that point, so the exhibition is a very personal recommendation for Jay."

"I did end up buying a lot of the books for my granddaughter," Labov says.

Adults visiting the exhibition may find themselves remembering the wonder they felt learning about science as a child. But children may glean something more. At least, that's what the organizers hope.

Talasek explains exactly what that "more" may be with an anecdote. One of the illustrations comes from You Are the First Kid on Mars by Patrick O'Brien. In it, three space-suited figures stride across rusty soil to approach the glistening, solar-paneled back of a robotic rover on the surface of the Red Planet.

The book itself inspired an astronaut to write the author with compliments: "This is the kind of book that I dreamed of as a kid, and the reason I became a physicist and astronomer. This is the first time since the 1970s that I have seen the excitement of space travel conveyed in a way that is both inspiring and plausible."

"Igniting the Imagination: Selections from the Collection of the Mazza Museum" is on view through August 7, 2017, at the NAS Building, 2101 Constitution Ave., N.W., Washington D.C. Visitors get in for free, but a photo ID is required.