How Kyle Meyer’s Photo-Tapestries Give Voice to a Silenced Community

The New York artist combines digital photography and African fabrics to create deeply textured portraits of persecuted Swazi men

When artist Kyle Meyer began photographing gay men in Swaziland, or eSwatini, five years ago, his subjects were initially wary about the exposure. Their concern was justified: Same-sex relationships are against the law there, and people who are suspected of being gay risk unemployment, ostracism and even violence.

“The LGBT community is pushed into a corner,” says Meyer, 33, whose series “Interwoven” explores sexual and gender identities in the southern African country. Meyer, who is openly gay and lives in New York, was forced back into the closet when he began traveling to Swaziland. “I could have easily ‘disappeared,’” he says.

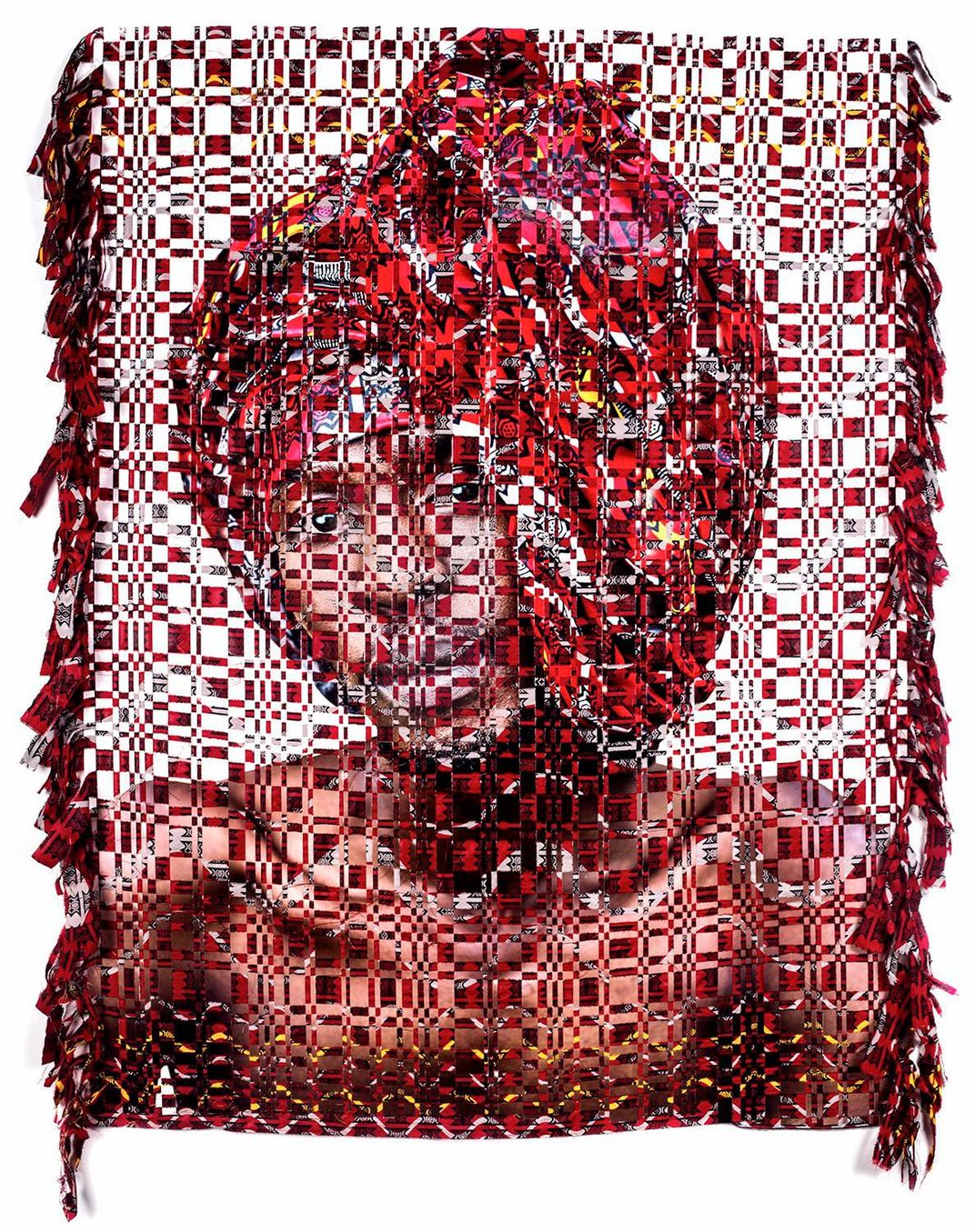

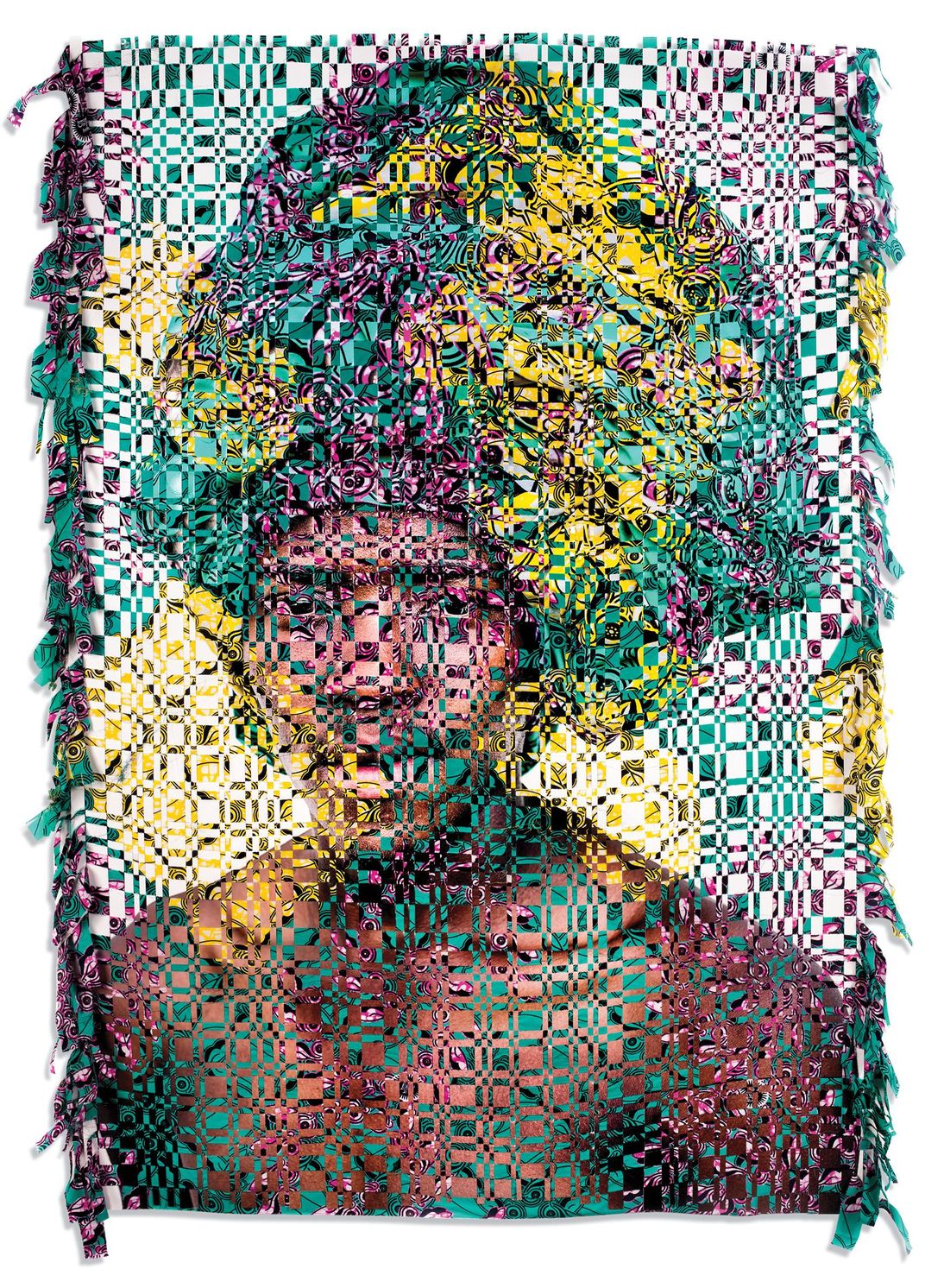

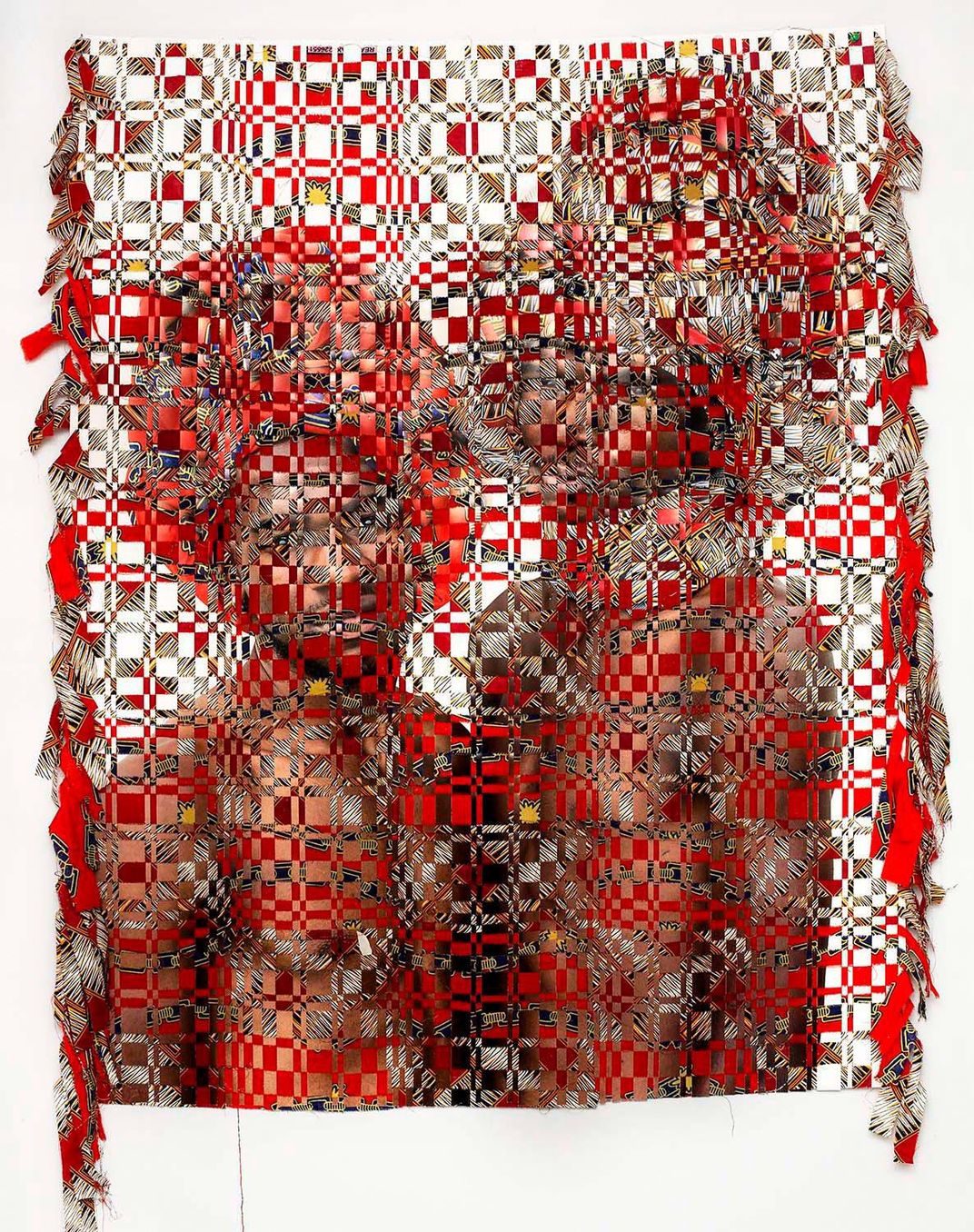

Despite their anxieties, the men who agreed to have their portraits taken for the project, on view this month at the Yossi Milo Gallery in Manhattan, seemed to relish the idea of finally being seen for who they are. Inspired by the vibrant colors of Swazi wax cloth, Meyer asked them to pose wearing elaborate headdresses in patterns each man chose from fabric collected at a local market. Because the style is traditionally associated with Swazi women, the photo shoots offered a rare chance to play with gender norms and celebrate each man’s individual sense of beauty. “They just wanted to be heard,” Meyer says.

After every visit to Swaziland, Meyer returns to his Hudson Valley studio, where he prints the images on paper up to seven-and-a-half feet high. He then shreds the photographs and the fabric from the head wraps, and, using a technique he learned from Swazi basketmakers, spends as much as 60 hours weaving them together. It’s a meditative process—both craft and ritual—that adds a human touch to the otherwise mechanical medium of digital photography, and transforms what might simply be a striking image into an imposing, richly textured physical object. One critic praised the undertaking as “the perfect marriage of subject matter and process.” It is also practical: Meyer’s approach partially obscures the men’s identities, much as they are forced to hide their true selves behind what the artist calls “the fabric of society.”

It remains too dangerous to display his tapestries in Swaziland, but Meyer is hopeful they will be seen there one day. This past June a gay rights group organized the country’s first Pride parade, a festive—and peaceful—march through the capital.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/55/4d/554dedb6-d71b-45ab-97b8-c0e8a6cbd5ee/nov2018_a01_artmeyer.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)