From the Castle

Hello? Hello?

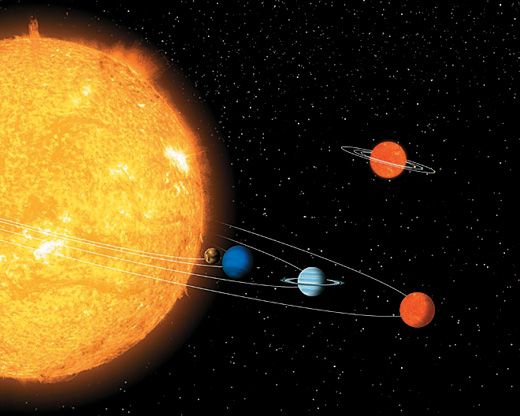

In all likelihood, we are not alone. Astronomers are quite certain there is no intelligent life elsewhere in our solar system, but given recent discoveries of nearly 300 "extrasolar" planets, there's an excellent chance life exists elsewhere in our galaxy. But can we find it? Smithsonian astrophysicist Daniel Fabricant explains: "You need to first discover a rocky planet like Earth, with temperatures to sustain oceans of liquid water, revolving around a nearby star in the Milky Way." The known planets outside our solar system are typically like Jupiter, gaseous giants lacking a solid surface and surely inhospitable to life.

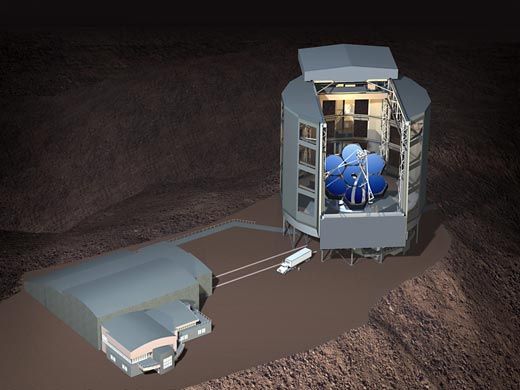

I recently returned from northern Chile's Las Campanas Observatory, which is operated by the Carnegie Institution. Thanks to clear skies, calm air and sufficient distance from city lights, it is an ideal place for astronomers to study the universe. With 21-foot-diameter mirrors, the observatory's Magellan Telescopes peer out at galaxies and supernovae, while new instruments analyze the spectral composition of light from galaxies billions of light-years away.

Most extrasolar planets have been revealed by observing their host star, or sun. An orbiting planet's gravity tugs on the star, causing it to wobble. Unlike planets, most stars are visible from great distances, so even a tiny wobble—or the minute dimming of the star as an orbiting planet passes in front of it—can be detected by highly sophisticated instruments. No direct photograph of an extrasolar planet orbiting a sun-like star exists.

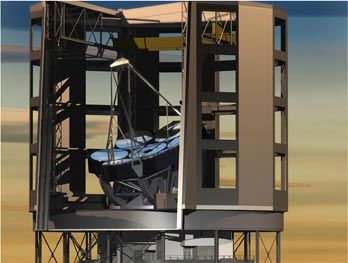

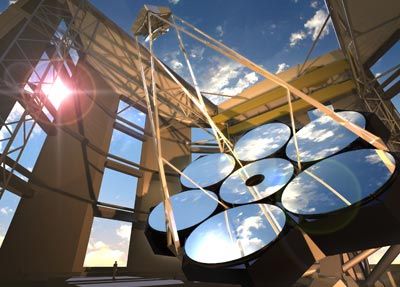

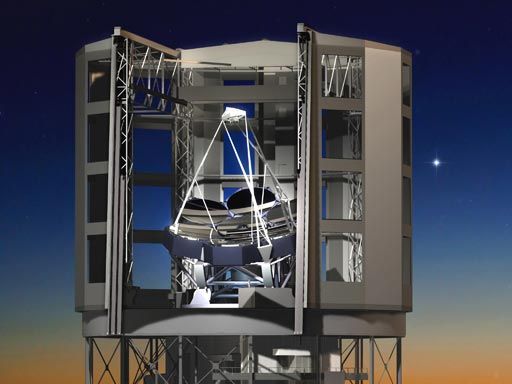

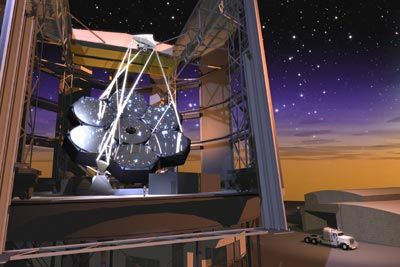

That will change. With an 80-foot-diameter mirror, a new Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) will have the resolution needed to photograph young Earth-like planets when they are forming around a star and are still hot enough to be visible. Planned for Las Campanas in about a decade's time, the GMT will collect ten times the light of today's Magellan Telescopes and will possess more precise instruments to detect stars wobbling in synchrony with orbiting Earth-like planets.

The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is joining a consortium comprising Carnegie and other research institutions and universities to help lead this great 21st-century adventure. With both private and government funding, the consortium will design and build the GMT, at a projected cost of $600 million. It should be able to locate other potentially habitable planets and help us understand how they were formed. "If this grand endeavor is successful," Fabricant says, "we may find a dozen Earth-like planets less than 50 light-years away—possibly our best hope for discovering life elsewhere in the universe."

Cristián Samper is Acting Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution