The Mystery of the Airplane in the Fishing Shed

Solved—almost 100 years later.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/35/b0/35b0e286-2827-4184-b1e2-c319681ddcf6/14d_dj2018_modelf3_live.jpg)

Having worked at the Cradle of Aviation Museum for decades, I have learned that treasures sometimes turn up unexpectedly. One day in 2012, I got a phone call from a fisherman in Mattituck, on the eastern end of Long Island. It seems he was cleaning out his boat shed when he found part of an old airplane, and he wanted to know if we wanted it.

Long Island has a rich aeronautical heritage, and old airplane parts turn up with some regularity. We’ve obtained several rare items over the years through such vague phone calls, so I figured it was worth the drive out east.

I arrived at the boat shed, which was dark, dirty, and crammed with the detritus of many years of commercial fishing, and the fisherman showed me a fairly deteriorated wood wing that appeared to have been part of an unknown type of aircraft. He told me that Grampa (also a fisherman) had owned a couple of airplanes in the 1920s and ’30s, one of them a seaplane he flew right from the dock next to the boat shed. I had no idea what the wing was from: It looked like a 1930s biplane to me—not very exciting, and I gently prodded the donor to see if there might be any other odd bits of old airplanes lying about.

He recalled an old radiator that he thought was from the flying boat, so we began rummaging around the shed. Soon the intact—but rusty—radiator was found. Now this was interesting. It was clearly from an early airplane—very early. The fisherman told me that the rest of this airplane had been stored in the rafters of the boat shed well into the 1970s, at which time it was thrown out to make space for their fishing gear. The museum I work for was created in the late 1970s; if only the fisherman’s family had held on to the old airplane just a little longer, maybe they would have heard of the founding of an aviation museum on Long Island and promptly called us to come fetch the wreck. One thing my experience in the airplane restoration business has taught me is that virtually anything is restorable, especially if all of the parts remain.

There was no engine for the aircraft: The Mattituck fisherman was pretty sure Grampa had sold it many years earlier, while the rest of the airplane was left to rot away in the boat shed. Nonetheless, I grabbed the radiator and arranged for a truck to pick up the wing. I was starting to wonder just what the East End fisherman had thrown out three or four decades ago.

It turned out that the wing was from a 1930 Buhl Bull Pup, and it had nothing to do with the flying boat. The radiator, however, was a different story. The brass polished up nicely, and by comparing it to archival photographs, I eventually found that it perfectly matched the radiator of a 1917 Curtiss Model F flying boat. In addition, the radiator itself held one great clue: In one corner I found the stamped image of a U.S. Navy anchor. Clearly the radiator had at one time been attached to a U.S. Navy aircraft. Knowing what I do of Long Island aviation history, I could deduce that it belonged to a World War I flying boat, a type based on Long Island during the war. The aircraft would have been a Curtiss Model F. That type is beyond rare: It is virtually extinct.

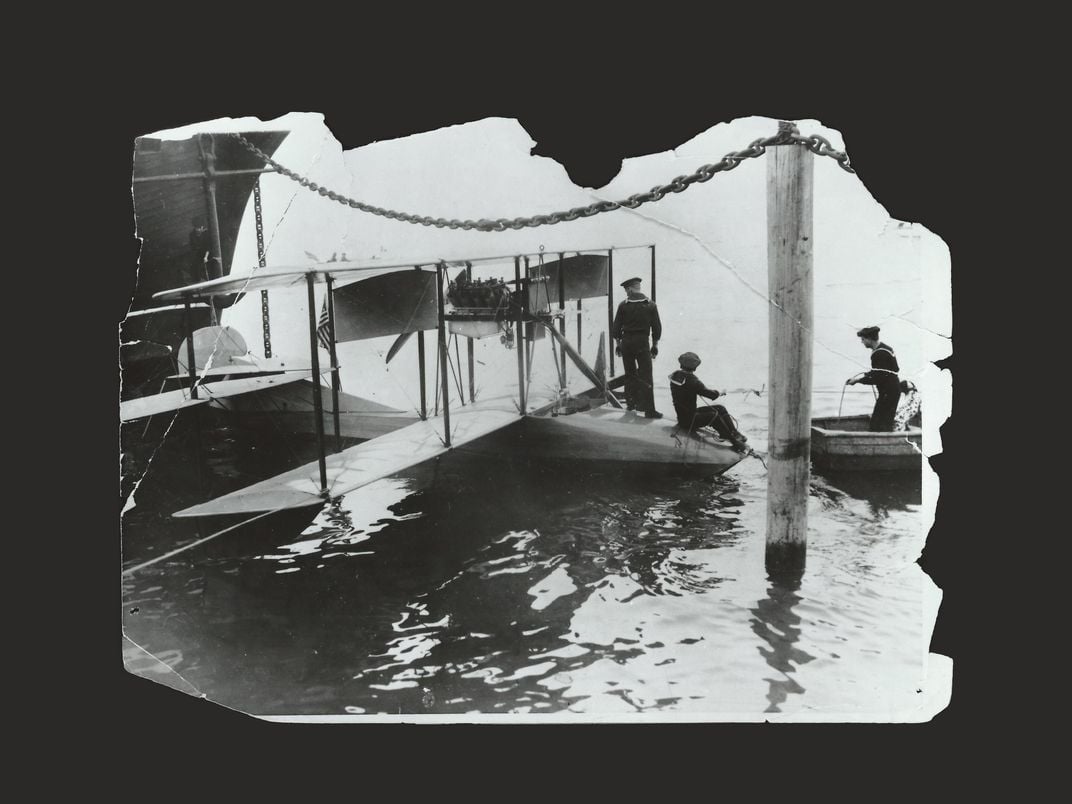

The Curtiss Model F was an improvement over the 1912 Model E, the Navy’s first boat-hulled aircraft. First produced in 1913 at Curtiss’ Buffalo plant—almost entirely for the military—Model Fs were sold to the government for $6,000 apiece. With a top speed of 65 mph, the F was the Navy’s primary training aircraft during the war. The pilot and student, or observer, sat side by side in an open cockpit. Like all early aircraft, the Model F was underpowered and provided only marginal control, especially while turning. Not surprisingly, training accidents were common.

During World War I, several Navy installations on Long Island operated Model Fs. At Huntington (and later Port Washington), the famed First Yale Unit—the beginning of the Naval Air Reserve—used them for flight training. Units at the Bay Shore and Rockaway Naval Air Stations flew them both on training missions and anti-submarine patrol. Since the Cradle of Aviation Museum had no Navy artifacts from that early era, I was thrilled to put the now-shiny radiator on display in the World War I gallery. To my surprise, however, it would not be lonely for long.

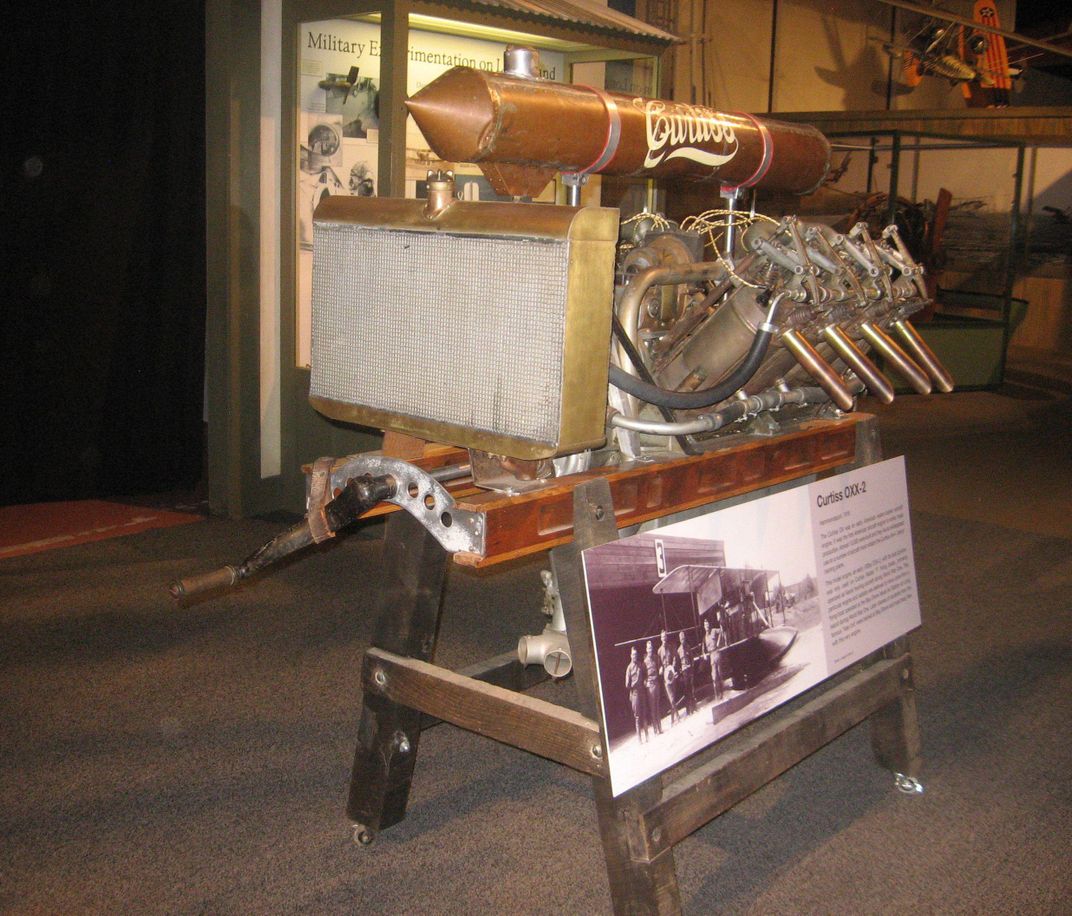

In the summer of 2013, during a conversation with Joe Erale Jr., an acquaintance who restores antique airplanes, I learned that he was making room in his workshop by disposing of a disassembled Curtiss OXX-2 engine. The OXX-2 was developed in 1915 by Curtiss—solely for use on the company’s Navy Model F flying boats. Joe asked if I had any interest in it, and I jumped. Within days I was in his workshop, looking over the various parts of the rusty engine.

His father had bought the water-cooled V-8 engine from Henry Bender, a colorful character who operated a decrepit airport in Brentwood, Long Island, from the early 1930s into the 1950s. Bender’s airport was legendary for being littered with the carcasses of old airplanes and automobiles. Bender had dumped the OXX-2 engine in his chicken coop, where, over the decades, caustic chicken droppings had rotted out the bottom of the oil pan.

My restorer friend also gave me a 1932 letter from Bender, asking permission from the Department of Commerce to mount this very OXX-2 engine in a Curtiss Robin aircraft. We don’t know if Bender ever actually did it, but the letter proves that he had acquired the engine by 1932. Since Bender lived at the airport and never ventured far, he almost certainly purchased the engine locally.

So where would Bender have purchased a World War I Curtiss flying boat engine on Long Island? From the grandfather of my radiator donor, once he stopped flying his Model F. I was sure that the radiator and its long lost engine could have come off nothing else. I was now inspired to dig further to see how the old Navy flying boat came to be in private hands in Mattituck in the 1920s.

In the back of my mind, I recalled an interesting booklet in our museum’s archives concerning the sale of surplus Navy aircraft shortly after the end of World War I: “Catalogue of Seaplanes, Engines and Spare Parts for Sale at Fixed Prices by the Bureau of Supplies and Accounts—Navy Department, 1920.” Leafing through, I found that the Navy department had gathered up a large amount of war surplus aircraft and equipment from their bases in the greater New York area and disposed of all of these items—many so new they were still in their shipping crates—at bargain prices.

Included in the 1920 sale were no less than 18 Curtiss Model Fs, as well as many used OXX-2 engines. I was now fairly certain that our engine and radiator were once attached to a Model F that was stationed on Long Island during World War I, and possibly flown by the First Yale Unit, only to be dumped via a postwar government fire sale. It was then purchased by a fisherman in Mattituck—our fisherman’s Grampa.

Over the next nine months, some of our museum’s skilled volunteer restorers carefully cleaned and reassembled the rare engine. We added to it an old copper fuel tank and an original set of Curtiss aircraft engine mounts that an anonymous donor had given us some years earlier.

Today the cleaned-up and reunited engine and radiator are on display in our museum’s World War I gallery. We exhibit them as a tribute to the Curtiss Model F and to the Navy men who flew the seaplanes on Long Island 100 years ago. Every time I walk past the exhibit, though, I can’t help thinking: If only Grampa had held on to that airplane a little bit longer.