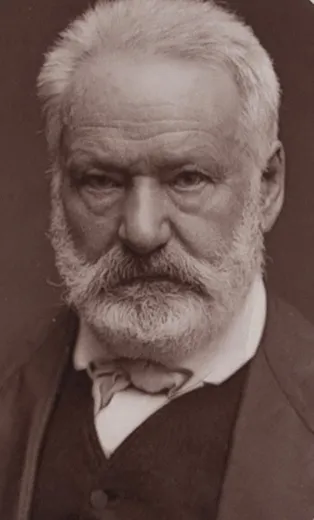

Take a Tour of Victor Hugo’s Paris

As a film version of his Les Miserables hits theaters, consider traveling in the French writer’s footsteps

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/victor-hugos-paris-hero-image.jpg)

Legend has it that Victor Hugo, the prolific French scribbler whose body of published work amounts to seven novels, 18 volumes of poetry and 21 plays, also holds the record for the world’s shortest correspondence. In 1862, while in exile on the British Isle of Guernsey for speaking out against Napoleon III, Hugo telegrammed his publisher “?” demanding the reaction to the release of his latest novel, Les Misérables. The reply: “!”

A century and a half later, “!” is still an apt description of Hugo’s epic masterpiece, which is still spawning numerous iterations on the page, stage and screen. In fact, many modern admirers may only be familiar with the iconic, 1980 musical production of the story created by Alain Boublil and Claude-Michel Schönberg. It is this stage version of Les Misérables that will be brought to life again this month in director Tom Hooper’s film starring Hugh Jackman as Jean Valjean, the redeemed convict who prevails in the face of repeated persecution, and Anne Hathaway as the downtrodden single-mother, Fantine. Amanda Seyfried will play Valjean’s adopted daughter, Cosette.

“The story is, in many ways, a love affair with Paris,” says Kathryn Grossman, a French professor at Pennsylvania State University who has authored four books on Hugo and Les Misérables. She notes that at the time of its release, Les Mis was both a call to arms for the French people and a lamentation of the “old Paris” that Hugo loved.

The controversial urban planner, Baron Haussmann, razed much of Hugo’s old Paris in the mid-19th century while the writer was in exile. The labyrinth of narrow, interweaving streets and hidden neighborhoods, relics of the medieval age, was leveled into the broad, sidewalk-bordered avenues that define modern Paris. This was both an effort to quell the city’s rampant congestion and the disease it fostered, and to prevent the building of revolution barricades. Today, though, it is still possible for travelers to find echoes of the Paris that Hugo once knew, from the house where he lived and the places he frequented, to the subterranean abyss that haunts the pages of the author’s most enduring novel.

The first stop for any Hugophile in Paris is undoubtedly the writer’s home-turned-museum on the second floor of the Hôtel de Rohan-Guéménée, where he lived from 1832 to 1848 with his wife Adèle and their four children. It was in this apartment, in the crimson-draped drawing room, that Hugo solidified his position as the father of French Romanticism. It is also the place where he wrote two collections of poetry, plays such as “Ruy Blas” and “Les Burgraves,” and a portion of Les Misérables. He started Les Mis in 1845 and worked for 17 years, spending the entire last year at Guernsey making corrections—eight hours a day—to the manuscript.

The museum is divided to illustrate the three sections of Hugo’s life: before, during and after exile. It contains hundreds of his drawings and is decorated with artifacts collected by the writer during his travels. The China Room exhibition, which represents his exile in Guernsey, was designed by Hugo for his mistress, Juliette Drouet, and is scattered with romantic allusions to her.

6 Place des Vosges

75004 Paris

Tel: 01 42 72 10 16

Metro: Bastille, Saint-Paul ou Chemin Vert

Hours: Tuesday to Sunday from 10am to 6pm; closed on Mondays and public holidays

Admission: Free for permanent collections

Church of Saint Paul – Saint Louis

Located in the Marais neighborhood, this Baroque church serves as the setting for Cosette and Marius’s nuptials in Les Mis. After the wedding, Hugo writes, “People halted in the Rue Saint-Antoine, in front of Saint-Paul, to gaze through the windows of the carriage at the orange-flowers quivering on Cosette’s head.” The Jesuits constructed Saint Paul-Saint Louis from 1627 to 1641, and the church’s 180-foot dome, intricate carvings and shadowy corners appear much as they did 200 years ago. Hugo was a parishioner of the church and donated the shell-shaped holy water fonts on either side of the entrance. Like Cosette, Hugo’s daughter Léopoldine was married in Saint-Paul in 1843.

99 Rue Saint-Antoine

75004 Paris

Metro: Saint-Paul

Paris’s second largest park is one of the most beloved spots in the city, for locals and visitors alike. Just south of Luxembourg Palace, where the French Senate meets, the garden was created in the early 1600s by Marie de Medici and modeled after parks in her native Florence. Hugo was just one of many writers to appreciate Luxembourg’s charms: Baudelaire, Sartre, Balzac and Hemingway were also frequent guests. In Les Mis, Luxembourg’s tree-lined alleyways and private nooks offer the perfect place for Marius to observe Valjean and Cosette on their daily trips to the park, and later to catch Cosette’s attention for the first time, “one day, when the air was warm, the Luxembourg was inundated with light and shade… [and] the sparrows were giving vent to little twitters in the depths of the chestnut trees.”

Rue de Médicis Rue de Vaugirard

75006 Paris

Tel: 01 42 64 33 99

Metro: Odéon

Hours: Opens between 7:15 a.m. and 8:15 a.m. and closes between 2:45 p.m. and 9:30 p.m., depending on the season

Louis XIV established the world’s longest-running national theater in 1680 with a royal decree signed at Versailles. In 1830, Hugo—by then a driving literary force in Paris—set out to bring Romanticism to the steadfastly conservative Comédie-Française with his controversial new play, Hernani. While the critics organized to boo the play off the stage, Hugo found himself at the head of a young Romantic army, literally. His supporters arrived opening night dressed in eccentric outfits, ate and relieved themselves in the theater, and rose to meet their bourgeois dissenters with applause, jeers and fisticuffs. The ‘Battle of Hernani,’ as the melee was later known, played out 39 times, and it became a spark plug for Paris’s greater societal and political tensions. Today, visitors to the company’s three theaters can enjoy tamer shows by some of its most famous playwrights, Jean-Baptiste Molière and Jean Racine, and even Hugo’s “Hernani,” which will run through February 2013.

Salle Richelieu (company’s main theater)

2 Rue de Richelieu

75001 Paris

Tel: 33 825 10 16 80

Metro: Palais Royal-Musée du Louvre

One of Hugo’s favorite spots to eat was the Grand Véfour in the Palais-Royal, which first opened its doors (as the Café de Chartres) in 1784. Though the menu has changed, the restaurant’s gilded frames, neoclassical paintings and mirrored walls are original. During the 19th century, the Véfour served as a hangout for the literary elite; Hugo and his friends even ate there before the “Battle of Hernani.” The writer’s order was always the same: vermicelli noodles, mutton and white beans. Today, the Michelin-starred restaurant, helmed by Chef Guy Martin, is known for rich French dishes such as duck liver ravioli and Prince Rainier III pigeon. Reserve a seat at the “Hugo table” near the window, with its courtyard view.

17 Rue de Beaujolais

75001 Paris

Tel: 33 1 42 96 56 27

Metro: Pyramides, Palais Royal-Musée du Louvre

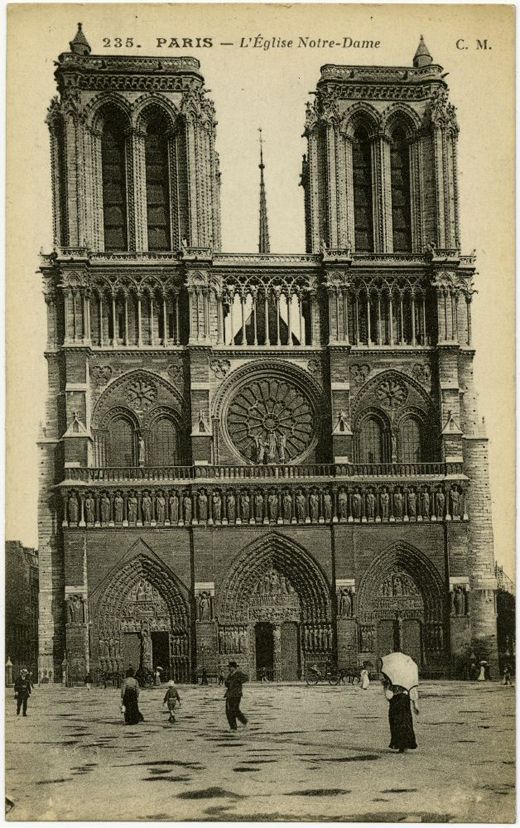

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831), Hugo’s great tale about a disfigured bell ringer and a 12th-century cathedral, made him the most famous writer in Europe. Hugo was a frequent visitor to the church, and at its heart, Hunchback is a story about preservation; when the book was published, most Parisians—when they thought of it at all—saw Notre-Dame as a shabby, moth-eaten antiquity. The novel’s popularity drew thousands of tourists to the grand edifice on the Îsle de la Cité, a natural island in the Seine, and it was finally restored in 1844. Today, visitors still flock for a chance to view the cathedral’s Gothic bell towers, flying buttresses and rosace stained-glass windows. Notre Dame offers free, hour-long tours each day, with information on its history, architecture and more.

6 Parvis Notre-Dame, Place Jean-Paul II

75004 Paris

Metro: Cité or Saint-Michel

Hours: Mon-Fri, 8 a.m. to 6:45 p.m.; Sat-Sun, 8 a.m. to 7:15 p.m.

Musée des Égouts de Paris (Paris Sewer Museum)

Paris’s underworld features heavily in Les Misérables, most famously its sewers, which once branched for a hundred miles beneath the city’s cobbled streets. It is here that Jean Valjean escapes in one of the book’s most dramatic scenes, fleeing the barricade with a wounded Marius on his back. “An abrupt fall into a cavern; a disappearance into the secret trapdoor of Paris; to quit that street where death was on every side, for that sort of sepulchre where there was life, was a strange instant,” writes Hugo. Baron Haussmann’s overhaul left few stones unturned, including the black, squalid sewer tunnels of Hugo’s day. But, visitors to the city can still catch a glimpse of Paris’ underground at the Musée des Égouts, which offers hour-long tours chronicling the sewer system’s modern development—no hazmat suit required.

Face au 93 Quai d’Orsay

75007 Paris

Tel: 33 1 53 68 27 81

Metro: Alma-Marceau

Hours: Mon-Wed, Sat-Sun 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. (October-April), 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. (May-September), Closed Thursday and Friday.

Admission: adult/child €4.30/3.50

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.