It happened just before dawn. The murmur of bat wings fluttered above me, somewhere within earshot. I lay among the rocks and realized, not for the first time, that my camera was wildly insufficient. In the moonless, inky hours before the sunlight creeps back in from the east, there is very little to see. All I could do was listen to these sightless fliers feeding above me in the stillness.

Having spent my career working as a photographer in remote, hard-to-reach areas, it took me nearly two decades to fully realize that the least appreciated and often the hardest gems to document are not the vistas I chase with still cameras, but the auditory elements that surround them. It was that blanket of calm—layered with the notes of wind, wings and scampering claws—that remained with me long after my pixels were processed.

On one assignment, involving a 750-mile trek through the entire length of the Grand Canyon, I’d set out to create a visual inventory of the wilderness, but after some 500 thirsty, thorny miles, I starting craving not more lenses but a better microphone. I wanted to capture the choir of croaking frogs, the rare applause of rain on rock, the hum of tarantula hawks, the echo of lambs bleating, the wind carrying a change in weather. It was all such a marked contrast from the usual noises that engulfed my life at home: traffic, trucks, lawn mowers, airplanes, construction sounds, portable music beats, my phone buzzing.

My craving led me to Gordon Hempton, a self-described acoustic ecologist. Hempton has spent nearly four decades capturing what he calls the planet’s “jukebox” of natural sounds. He has recorded the music of insects and owls, mountain ranges and jungles, the rustling of prairie grasses and the echoing vibrations inside a log of Sitka spruce.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/82/36/8236a3df-9030-4e67-b84a-077ecbec1ab0/screen_shot_2020-09-14_at_124525_pm.png)

Hempton uses the word “silence” to describe what he’s after, even though he isn’t seeking a vacuum. He’s looking for the soundscapes that emerge when human noise disappears—antidotes to the din of a mechanical, beeping world.

“Silence is the think tank of the soul,” Hempton told me softly during a Skype interview earlier this year. “All religions share and revere silence.” He warned that quietude “is and has been on the road to extinction for a long time.”

He has the data to prove this. In 1984, after Hempton had spent some years chasing silence, he identified 21 places in his home of Washington State (an area of 71,298 square miles) that were free of human-made noise for intervals of 15 minutes or longer. In 2007, Hempton reported that only three of those places on his list still fit that criterion. Today, he believes a natural silence longer than 15 minutes is rare in the United States and all but gone in Europe. Even remote wilderness areas and national parks are frequently crisscrossed by jets, shrinking the average noise-free interval to less than five minutes during daylight hours.

This noise pollution is harming animals. A study last fall at Queens University Belfast found that human-made sounds threaten the feeding, migration and communication of more than 100 species of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles and amphibians. But noise pollution is also bad for our own health. It can lead to high blood pressure, heart disease, heart attacks, stress and insomnia. In 2011, the World Health Organization concluded that 340 million Western Europeans (roughly equivalent to the U.S. population) lost at least one million years of healthy life each year because of traffic-related noise.

Quietude, though, has been shown to promote the regeneration of brain cells in the hippocampus, which is key for learning, memory and emotion. Preliminary findings also suggest that it can be therapeutic for certain types of depression and dementia.

Hermits, writers and philosophers who sought solitude in the woods may have been on a more medicinal path than we’ve given them credit for. “Silence is the universal refuge, the sequel to all dull discourses and all foolish acts,” wrote Henry David Thoreau, the 19th-century transcendentalist, as he recorded natural sounds with the best microphone he had available: a pen.

Whenever I come back from an assignment documenting a quiet corner of the earth, I often notice how much clearer my mind feels. The quandaries of life seem simpler, my attention a tad sharper. Even after I reacclimate to the higher decibels of modernity, it feels as if the medicine of silence has eased my mental noise.

This became ever more noticeable during the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic when there were significant drops in tourism and travel, and industrial lockdowns. While many commented on the hushed tones of neighborhoods and the increased awareness of bird sounds again, a report in the journal Science reported that the lockdown was “the longest and most coherent global seismic noise reduction in recorded history.”

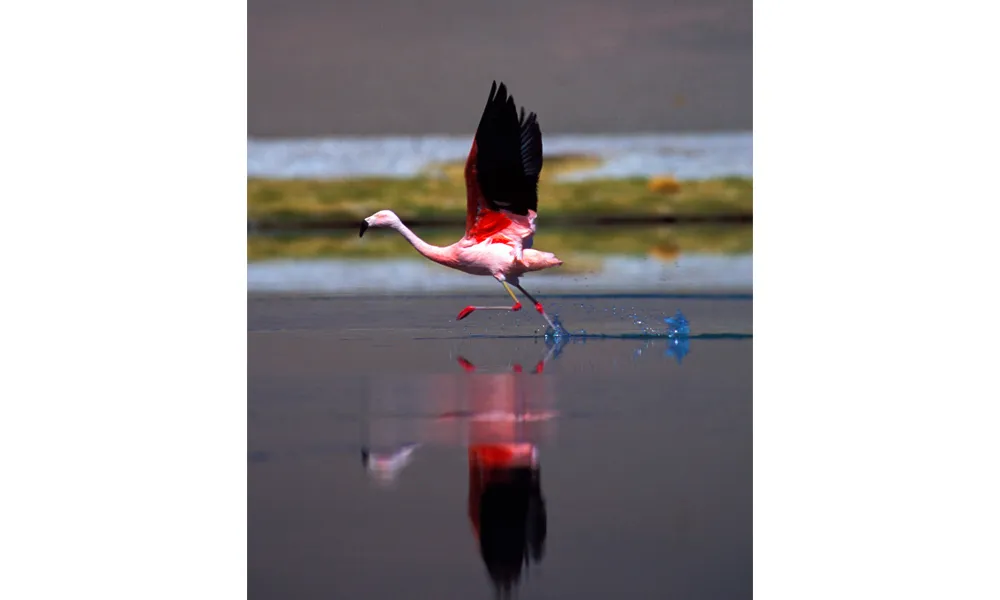

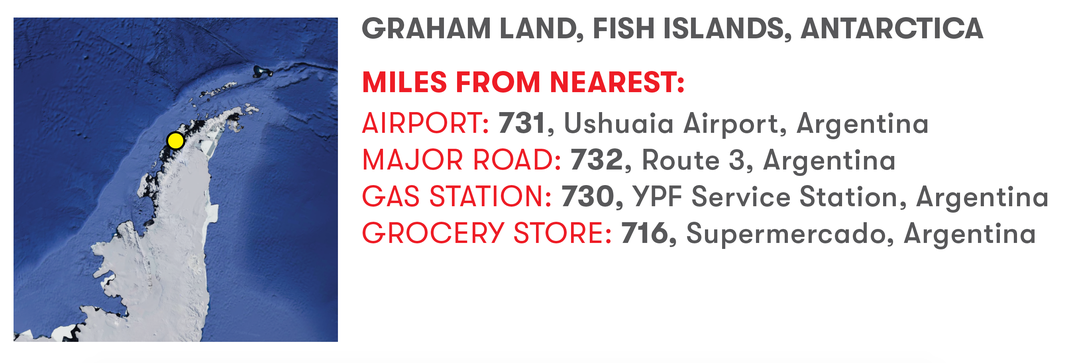

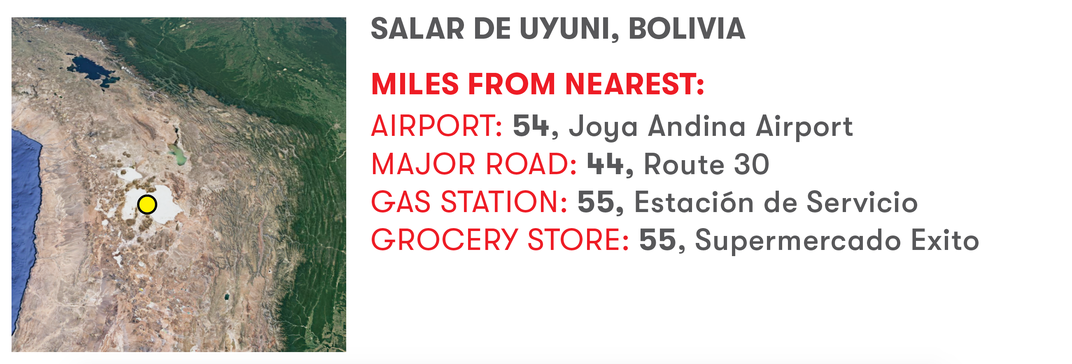

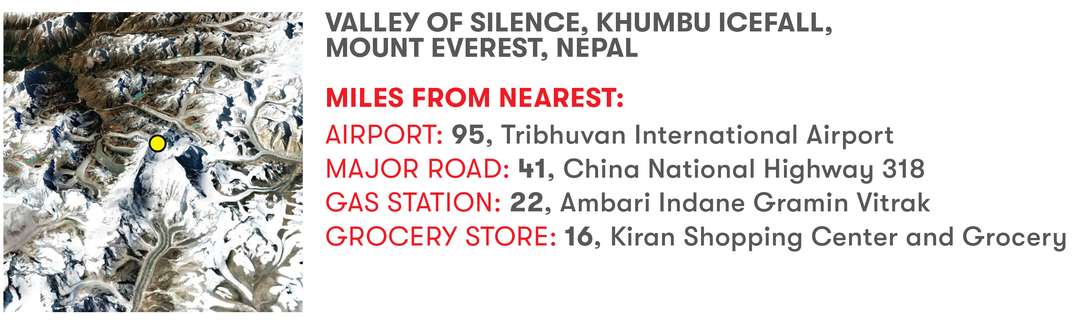

The images on these pages are some of my visual meditations on the sounds and silences of nature from throughout the years. They are the backdrop to the Khumbu lullaby of Mount Everest’s glaciers moving underfoot, the distant rumble of an elephant. They document the deep stillness in the basement of the Grand Canyon or the thin-air emptiness of the Altiplano’s ancient lakebed of the Salar de Uyuni. I hope these photos can serve as reminders of what the natural world has to tell us—if we listen.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2c/43/2c43d040-9925-49a1-9b2b-8421cef3bcb5/opener_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a8/d3/a8d351f6-549e-4a7a-a4b1-7698348c49f2/opener_white.jpg)