If Atlantic and Pacific Sea Worlds Collide, Does That Spell Catastrophe?

While the Arctic ice melt is opening up east to west shipping lanes, some 75 animals species might also make the journey

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2b/ca/2bcaa6cd-23a1-44ca-94b2-aa0c35c70523/mapnorthwestpassage.jpg)

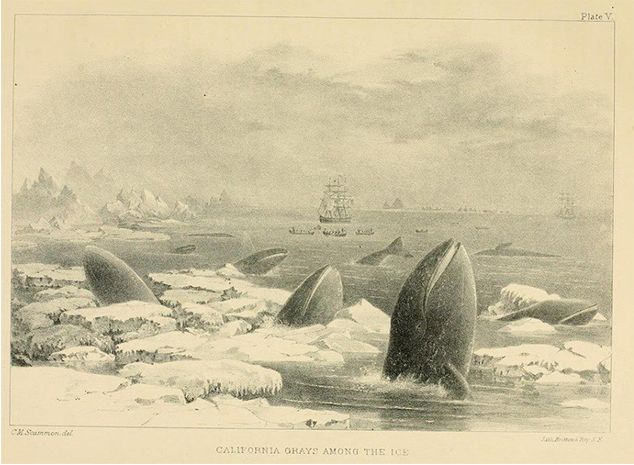

Citizen scientists all over the world are spotting animals far away from their natural habitats. Pacific gray whales were recorded in the Atlantic, swimming off of the coast of Israel and Africa. And the Manx shearwater, a bird native to the Atlantic, has been spotted on the Pacific Coast. These animals could be moving through the Northwest Passage, an Arctic sea route that connects the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans.

The Northwest Passage was once frozen with sea ice and nearly impassable all year long, creating a barrier that prevented marine mammals and many birds from traveling from one ocean to the other. But now due to global climate change, receding ice has opened a seaway through the Arctic Ocean during summer and fall.

This seasonal passage allows both people and animals to travel from the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic Ocean.

In a new study published today in the journal Global Change Biology, a team of scientists lead by the Smithsonian’s Seabird McKeon and Michele Weber estimate that as many as 75 species are likely to move from their current habitat to a new one because of the passage.

"We're seeing unprecedented migration in these animals," says co-author Kirsten Oleson, an ecological economist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

"They're moving from one place to the next, and they've never moved before," she adds. "All of a sudden their populations are mixing, [and] that leads to all sorts of conservation questions."

Lots of businesses are excited about the open passage because it means companies can one day quickly ship their products from the Atlantic to the Pacific. But all this open water isn't necessarily good for the animals that live in the area. Animals crossing from the Pacific to the Atlantic and vice versa can bring new diseases and use up valuable resources.

When animals from the Pacific meet their counterparts on the Atlantic, they're usually similar, which means they can mate. But the Pacific Ocean is very different from the Atlantic, so offspring with foreign parents might be born without the physical adaptations needed to survive.

"Genetic diversity can be beneficial to a population [but] you can have problems when you have a stranger mixed into your group and their genes aren't suited to the environment," says McKeon, who is an ecologist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and works out of the Institution’s Marine Station in Fort Pierce, Florida.

Animals traveling through the Northwest Passage may also carry diseases. For example, some of the seabirds on the East coast carry Lyme disease, a condition that's transferred to humans via ticks. If these birds travel to the West coast through the Northwest Passage, this could cause problems for the local Pacific birds and humans, says Rachel O'Malley, the department chair of environmental studies at San Jose State University.

Predators moving from ocean to ocean can also create big problems. When you add a new top-level predator to an ecosystem, like a killer whale, they can wipe out all the mid-level predators. This has a waterfall effect and can completely restructure the food web, O'Malley says.

The melting sea ice also has some serious environmental policy implications, Oleson says. A lot of conservation laws are based on specific animal populations living in certain areas. As animal populations move from ocean to ocean, they cross into international waters, which makes them more difficult to monitor and protect.

"The Northwest Passage is a frozen landmass [in] the territory of Canada," Oleson says. "But once it's open and navigable, it falls under the law of the sea so none of the legal protections that Canada could initiate are applicable anymore."

The Northwest Passage isn't the first case of an open passageway between two bodies of water. The Suez Canal in the Mediterranean and the Panama Canal are both prime examples. However, this is the first time that scientists will be able to track, in real time, how these changes affect the world, says Weber, an evolutionary biologist at the Smithsonian’s Natural History Museum.

"The world is always changing," Weber says. "This is an opportunity to [watch it] as it's happening."

For the study, published this week in Global Change Biology, scientists ran web searches to look for mentions of "vagrant" animals—observations of animals that have traveled outside their usual habitat.

"It was a scavenger hunt more than anything else," McKeon says. "Most of the data is coming from citizen scientists—birders or whale watchers are reporting their sightings with such rigor and veracity that we can start putting them together and this pattern starts to emerge."

The next step is to gather even more information from citizen scientists. Researchers are building a program that will scan the Internet for mentions of animals they think might use the Northwest Passage. The researchers plan to use this information to look at animal migration patterns so they can better protect ecosystems and make predictions about the future.

"This paper is a red flag," Oleson says. "We need to set up really effective monitoring systems. We lack information about what's going on, and that lack of information can undermine the protection of animals."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Photo_Bloudoff.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Photo_Bloudoff.jpg)