Without This Camera, the Emerald City Would Have Been the Color of Mud

That dramatic Dorothy in Oz moment was brought to you in living color by the DF-24 Beam Splitter

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ec/75/ec758fc5-e571-42e3-ae4a-525f4e2968dc/nmah-jn2014-3761.jpg)

Just imagine if the Yellow Brick Road—that magical highway in the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz—had been pale gray. Or, if the Emerald City had been a slightly darker gray. Or, if those glowing ruby slippers had been just another pair of bland party pumps.

Hard to picture it, and even harder to imagine that a colorless Oz would have lodged in America’s movie memory in the way the ballyhooed, multi-hued classic has.

One of the most memorable sequences in the film offered both visual proof that Dorothy and Toto weren’t in Kansas anymore and a perfect metaphor for a profound change in the nature of movies. The moment comes early, after the tornado has whirled Judy Garland from a hardscrabble farm to a hero’s welcome in Munchkinland after her house lands on a wicked witch.

The Kansas scenes are filmed in Dust Bowl sepia, but the province of the Munchkins is shown in dazzling color.

One of the revolutionary cameras that made that color possible—technically known as the DF-24 Beam Splitter Motion Picture Camera—can be seen in the "Places of Invention" exhibition in the Lemelson Center on the first floor of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

The advent of color did not come about with The Wizard of Oz; moviemakers had used various methods to enliven their films, from hand tinting film to special filters (just as still photographers had found various alchemies to enhance black and white film).

The first all-color feature came out in 1935, according to Anjuli M. Singh, a Roger Kennedy memorial scholar at the museum. Singh says that there were also feature films that contained short Technicolor sections, so that though The Wizard of Oz used color on a grander scale, it was consistent with an industry pattern. Thus the introduction of color was not as seminal as the dramatic change from silent films to talkies in 1927, with The Jazz Singer giving voice to Al Jolson.

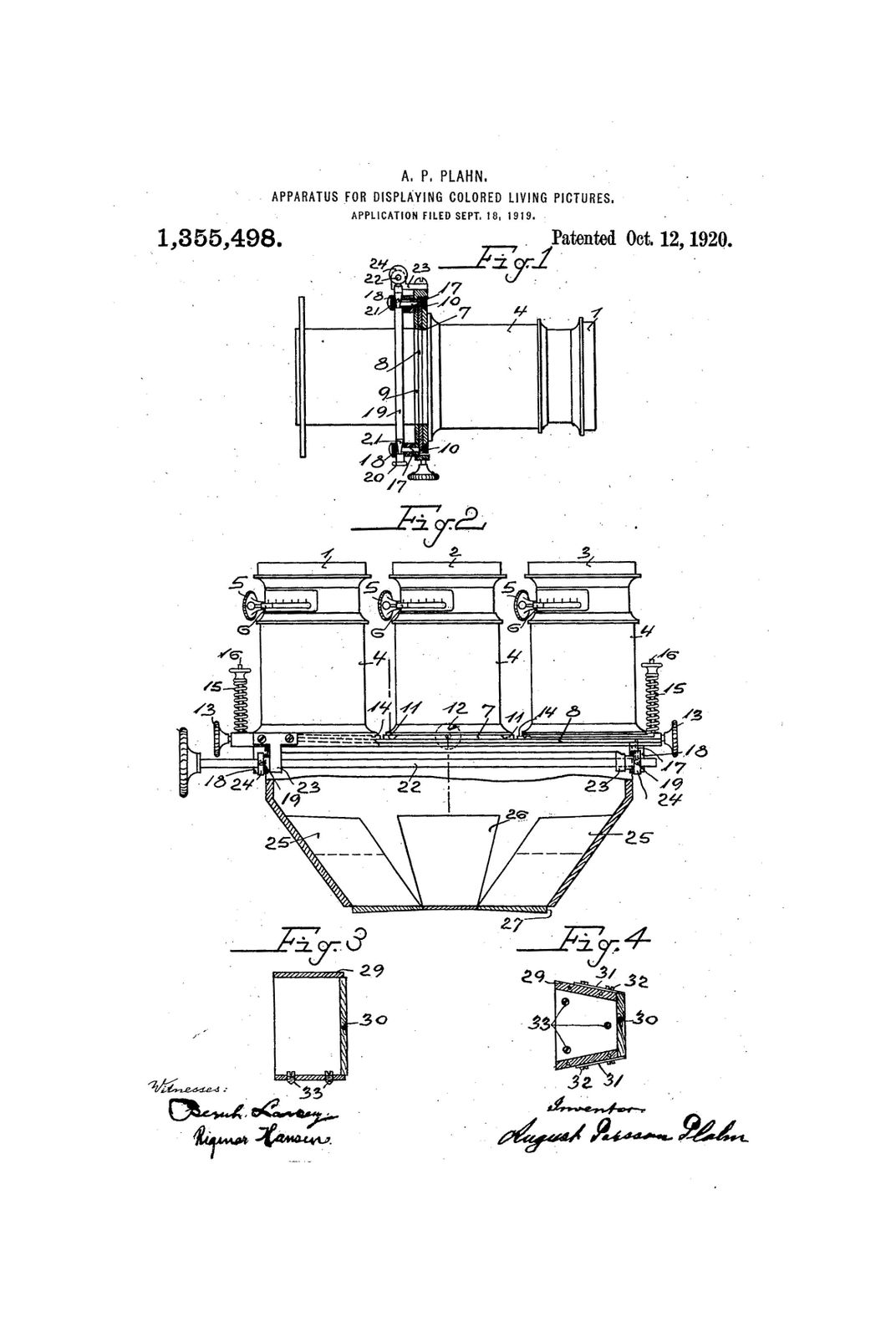

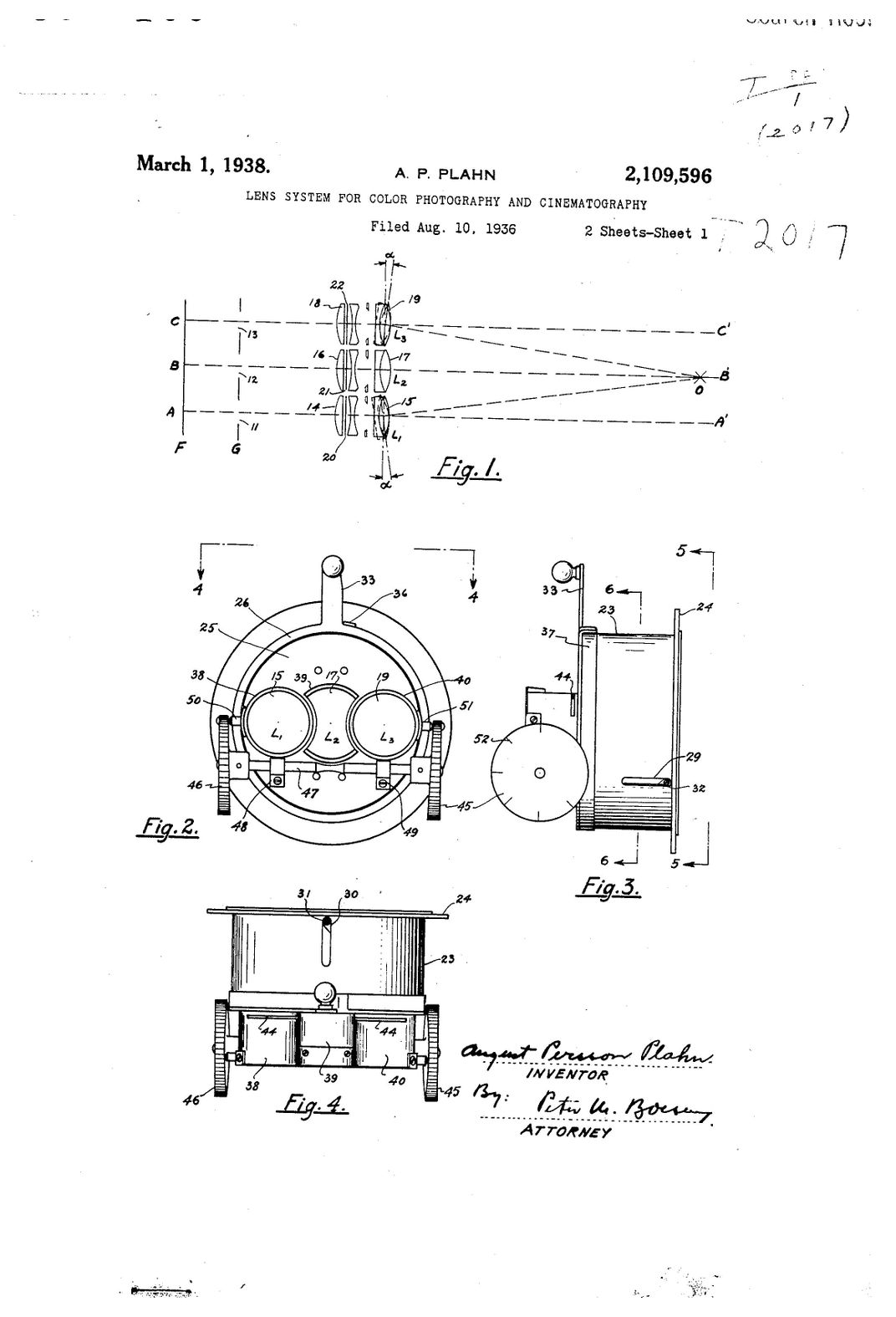

Credit for creating the first practical color movie camera goes to a Danish-American inventor, August Plahn, whose camera split images through three lenses using 70 millimeter film. Plahn was unsuccessful finding financial backing for his invention. The Boston- based Technicolor Company, with investments from that city’s bankers, was able to establish similar technology as the industry standard (a dominance the company retained for many years).

However, The Wizard of Oz, which came out in the same year as Gone with the Wind, another hit film in vivid Technicolor, made a telling point about the difference that color could make to the pleasure of audiences. Once Dorothy steps out of her front door and steps into Oz, nothing was going to be the same again.

The shift from shades of gray to vivid color may have been a powerful metaphor for the future of movies, but Singh considers the shift in the film a comment on the economic and social conditions in the United States at the time. “For Americans still in the midst of the Great Depression, and nervous about an impending conflict in Europe, to have seen the transition from drab, sepia Kansas—an evocation of their own world at the time—to the gorgeous Technicolor world of Oz was a much-needed escape.”

The DF-24 camera, invented in 1932, is one of several that were used by cinematographer Hal Rosson to film The Wizard. It is complicated and large, standing 106 inches high, on a wheeled sled almost six feet long, with the gadgety look that might be described as steampunk. The inner workings of the camera that exposed three separate strips of field in red, green and blue (combined in processing for full color) are enclosed in a blue casing that is called a blimp. Ryan Lintelman, a curator of the museum’s entertainment collection, says that this shell was necessary to baffle noise and also to provide fire suppression, since at the time highly flammable nitrate film was the standard stock.

Lintelman says that the Technicolor Company only built 29 of these cameras for use in the United States, so if more than one color film was shooting at the same time, casts and crews sometimes had to wait their turn for equipment. Technicolor didn’t sell the cameras to the studios, instead they rented them, and sent specialized operators and technical experts along with each one.

Not only did the Technicolor cameras change the way movies looked, Lintelman says, but they also changed how crews, actors and even writers worked. “In the original book, and in the original script that we have,” he says, “Dorothy’s ruby slippers are described as silver. Before shooting, they were changed to take advantage of Technicolor.” He added that the Ruby Slippers—also in the Smithsonian collections—are actually a dark burgundy, and look brighter red because of the powerful lighting necessary to get the most out of color film.

The lights needed in the filming of The Wizard were many, and powerful. According to Lintelman, 150 arc lamps were used to brighten the interior sets, raising the temperatures to 100 degrees or more (poor Tin Man!) and ultimately costing MGM around $225,000 in electric bills (in 1939 dollars). A fire inspector was on the set every day of the shooting because of the heat of the lights and the nitrate film. Many actors in the movie complained about eye problems that were blamed on the power of the lights.

There were no complaints from audiences, however, who made The Wizard of Oz one of the biggest hits of the decades, and still considered a classic today. The film made a megastar of Judy Garland, and enshrined other cast members such as Bert Lahr, Ray Bolger, Jack Haley, and Terry the dog as Toto. But some of the biggest stars, mentioned only at the end of the credits, were those Technicolor cameras.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)