Why Do Chinese Restaurants Have Such Similar Names?

Consistency and familiarity is the tradition

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2f/df/2fdf811a-36d0-4de1-a695-476be549112c/istock-503692580.jpg)

Chinese restaurants are ubiquitous across America from big cities to suburban strip malls to dusty back roads, to highway gas stations. They are frequently the heart of small towns. They offer up a familiar menu of comfort food, but also similar-sounding names. And that’s no accident. Even though the majority of the 50,000 Chinese restaurants in the United States are not large chain franchises, family-owned mom-and-pop shops adhere to a tried and true gustatory tradition.

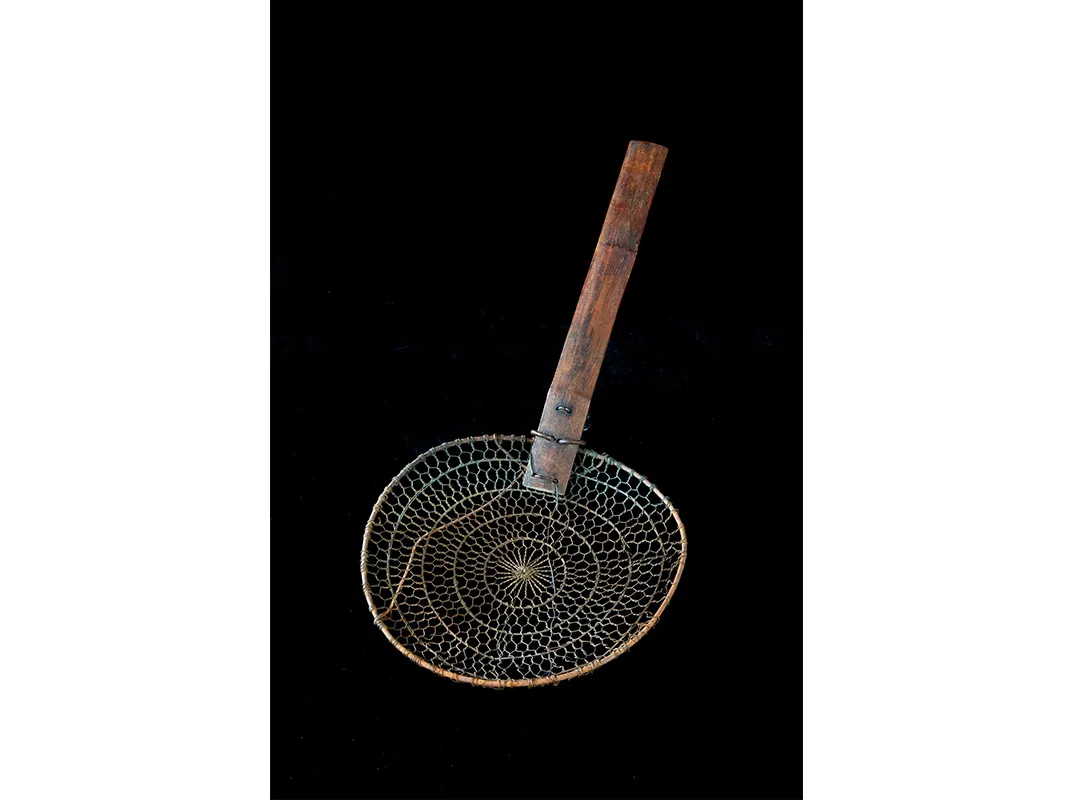

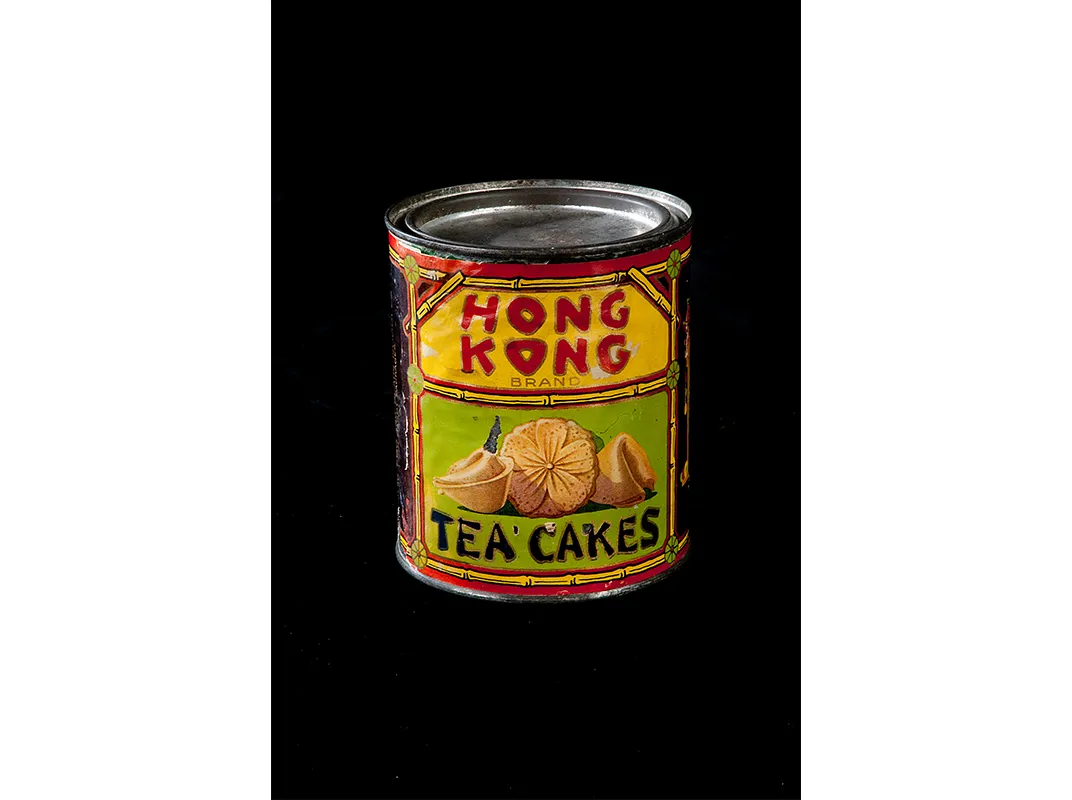

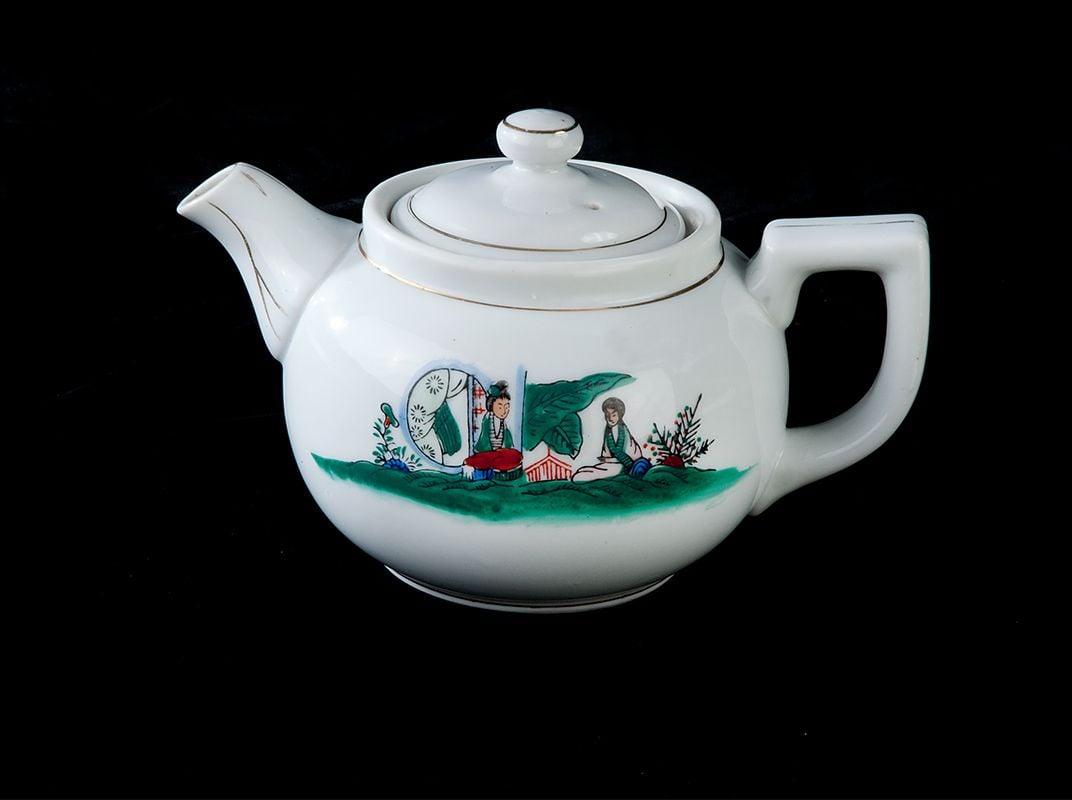

“Familiarity is one of their biggest selling points,” says Cedric Yeh, who as project head of the Sweet and Sour Initiative at the National Museum of American History, studies Chinese foodways (see artifacts below) and helped put together a 2011 exhibition on Chinese food in America at the museum.

Many Chinese restaurant names are chosen for their auspiciousness—out of the owners’ desire for success. They include words like golden, fortune, luck and garden. In Mandarin, garden is “yuan,” a homophone for money.

The word play, says Yeh, is usually lost on American diners. To Americans, some names may make no sense or translate in a funny way, says Yeh, whose parents had a Chinese restaurant named Jade Inn in Springfield, Massachusetts, when he was younger.

One of the words that means good fortune in Cantonese is spelled most unfortunately “fuk.” Restaurants incorporating that word have gotten lots of attention, especially in the social media era, says Yeh, who also serves as deputy chair of the division of Armed Forces History.

“I don’t think they ever stopped and thought about why that might attract attention,” says Yeh.

An online Chinese Restaurant Name Generator pokes playful fun at the stew of name possibilities, spitting out “Goose Oriental,” “Mandarin Wall,” “#1 Tso,” and “Fortune New Dynasty.” Auspicious, perhaps, but maybe not the catchiest.

But Chinese restaurant names are packed with significance to Chinese people. Take “Fragrant Harbor”—the name for Hong Kong, says Andrew Coe, a Brooklyn-based author of Chop Suey, A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States. Chinese people would understand that it’s a Hong Kong-style restaurant, he says.

Names—along with menus and decor—established by the first owner of a restaurant rarely change, even if the business changes hands multiple times, as they often do, Coe says. The Chinese restaurants follow a formula. “They believe in consistency and not scaring away the customers,” Coe says. If the name changes, it could mean a change in cuisine.

Most Chinese restaurants in America also get their menus, their décor and even their workers from a small group of distributors, most based in New York, although some are in Chicago, Los Angeles and Houston, a city with a growing Chinese population, Coe says.

Chinese restaurants—ones that also catered to Americans, and not just Chinese immigrants—didn’t start to proliferate until the late 19th century. The center of the Chinese food universe was New York City, where many Chinese ended up after fleeing racial violence in the American west. In the east, especially in the roiling immigrant stew that was New York City at the time, while anti-Chinese sentiment existed, it was no more virulent than the bigotry against other immigrants, Coe says.

Immigrants from Canton (the southern province that surrounds Hong Kong and now known as as Guangdong) opened most of the early U.S. restaurants. Cantonese influence continues to be strong, but with another wave of Chinese immigrants in the 1970s and 1980s, the cuisine and culture of Fujian province joined the American mix, along with dishes from Hunan, Sichuan, Taipei and Shanghai. And now, with growing numbers of Chinese students attending American universities, interesting regional influences are showing up in perhaps unexpected places like Pittsburgh, says Coe.

But the names all continue to be similar and say something to both American and Chinese diners, says Yeh. “You want to give the customer the idea that you’re coming to a Chinese restaurant,” he says. The restaurant also has to pitch itself as something more exotic than the Chinese place down the street, so it may become a little more fanciful with the name, he adds.

The Washington Post in 2016 analyzed the names of some 40,000 Chinese restaurants and determined that “restaurant,” “China,” and “Chinese” appeared together in about one-third of the names. “Express” was the next most popular word, with “Panda” running close behind, in part because there are more than 1,500 “Panda Express” restaurants, part of a chain.

“Wok,” “garden,” “house,” and “kitchen,” also were frequently used. “Golden” was the most-proffered color, and panda and dragon were the most well-used in the animals category.

The panda-China connection in restaurant names is a more recent thing, but both the dragon and phoenix are traditionally associated with Chinese culture and history, Coe says. “Imperial” also has deep connotations for Chinese people, evocative of its past. For restaurants, “it implies a kind of elevation of the food,” says Coe, but often, not much else might be a cut above. One of Coe’s favorite restaurants in Queens, “Main Street Imperial Chinese Gourmet,” has wonderful food, but is basically a hole in the wall, he says.

As far as Coe is concerned, the name is far less important than the food. “What most Americans seem to believe about Chinese food is that it should be cheap and not very exotic and served very quickly,” he says. They expect something a little sweet, greasy, not too spicy, no weird ingredients, and some deep-fried meat.

Cantonese food is delicate and light, with many steamed or boiled items. “It’s one of the great cuisines of the world,” says Coe.

But at restaurants that cater more to Americans, the food has been altered to fit those diners’ expectations “that it’s almost completely unrecognizable”—unlike the names.

It's your turn to Ask Smithsonian.

This summer, a new permanent exhibition entitled "Many Voices, One Nation," and featuring a number of the items collected from Chinese immigrants and restaurant owners, opens June 28 at the National Museum of American History.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)