What Climate Change Will Mean for the People of Oceania

On many maps the ocean is colored a uniform, solid blue. But for those who live off the waters, the sea is places, roads, highways

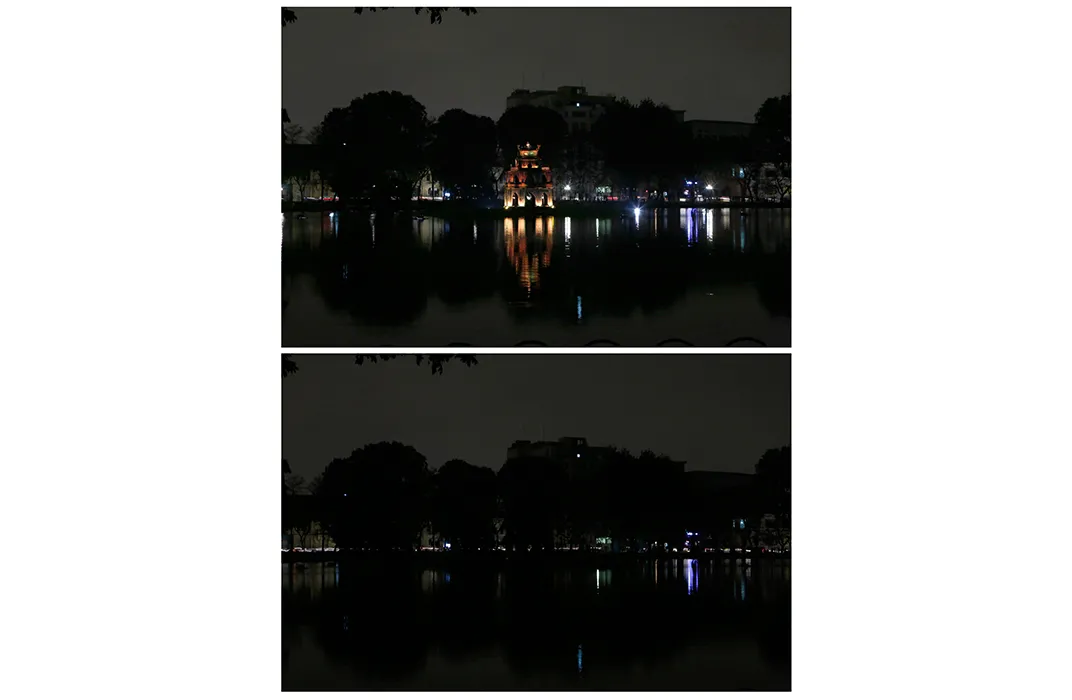

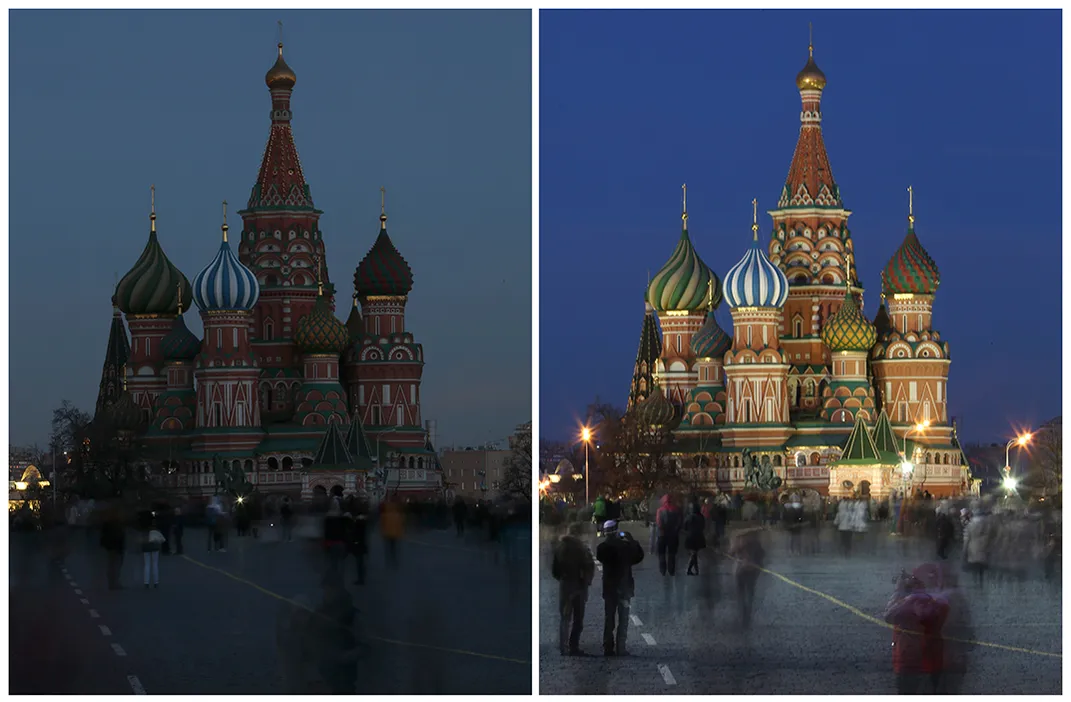

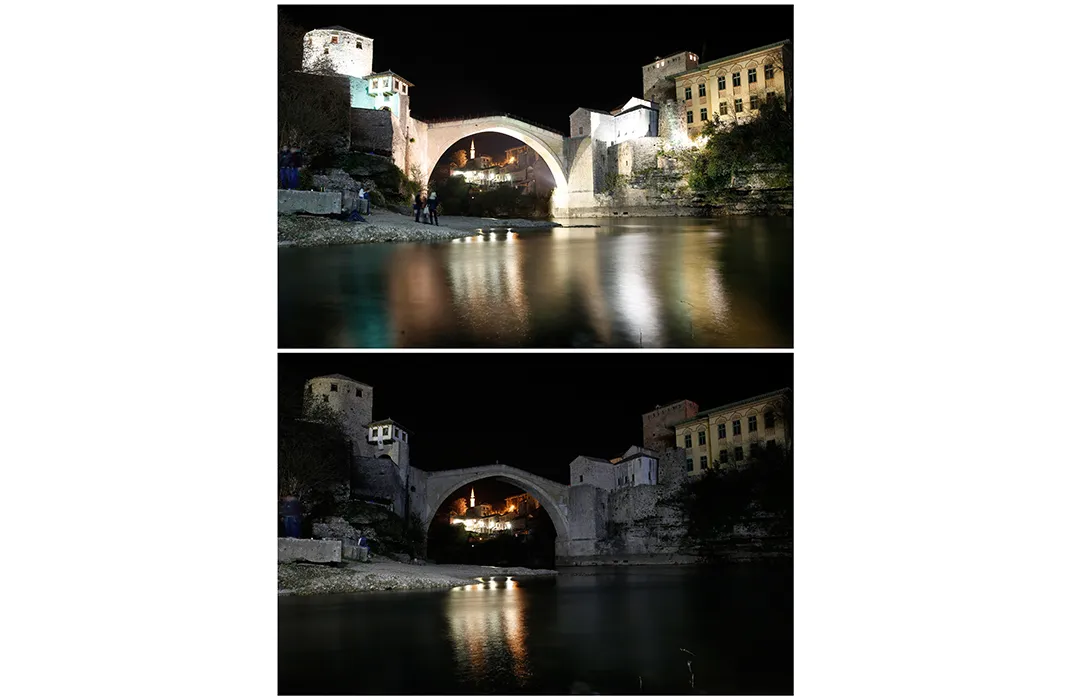

This Saturday, March 28, 2015, the planet will be celebrating the ninth annual Earth Hour, where people around the world will turn off their lights at 8:30 p.m. local time for one hour. The organizers see this event as a planet-wide movement, reminding us—for just 60 minutes each year—that there are small things that we can do to minimize carbon emissions that are causing climate change.

There is one "continent" that will participate hardly at all in Earth Hour, yet it is arguably the one continent most directly affected by climate change, and which will, in turn, affect the climate on the rest of the planet. It has the highest mountains, the deepest valleys, and the vastest plains. It is inhabited by an unfathomable numbers of species, plant and animal. It has a total area of 155.557 million square kilometers, including an estimated 157,000 kilometers of coastline. It is the largest continent—larger than all the landmass in Earth put together. Oceania—the "Liquid Continent."

For decades it was fashionable to speak about the “Pacific Rim,” which soon became equated simply with the word “Pacific.” To speak of the Pacific is to speak of North America’s West Coast, East and Southeast Asia, and—for the more bold—the Western countries of Latin America. That’s the Pacific Rim. In between—what some of us called the Pacific Basin—is another land entirely. A land rendered invisible by the “Pacific Rim”: Oceania.

One hears mention, in the talk about climate change, that certain small island nations in the Pacific—Tuvalu, in particular, and also Kiribati (pronounced KEE-ree-bahs)—are starting to disappear under the rising sea. As long as one thinks in terms of land continents, the loss of some tiny islands—just like the loss of some coastal Arctic native villages—can seem far away and insignificant. But Islanders are already cognizant of these effects:

- Loss of coastal land and infrastructure due to erosion, inundation and storm surges;

- Increase in frequency and severity of cyclones with risks to human life, health, homes and communities;

- Loss of coral reefs with implications for the sea eco-systems on which the livelihood of many Islanders depends;

- Changes in rainfall patterns with increased droughts in some areas and more rainfall with flooding in other areas;

- Threats to drinkable water due to changes in rainfall, sea-level rise and inundation;

- Loss of agricultural land due to salt-water intrusion into the groundwater;

- Human health impacts with an increase in incidence of dengue fever and diarrhea.

But the impact of climate change on the ocean has huge implications not just for islanders, but for the planet.

Our own Enivornmental Protection Agency tells us that as greenhouse gases trap more energy from the sun, the oceans are absorbing more heat. Though it is less noticeable to us on land, this gradual rise in ocean temperatures will not only bring rising sea levels, but changes to the movement of heat around the planet by ocean currents. This will lead to alterations in climate patterns around the world.

Because the ocean, not the land, is the primary driver of our climatic system. Changes to the ocean affect changes to winds. One result already has been flooding events on the East Coast of the United States linked to sea level rise and changing wind patterns.

Coral bleaching (which kills corals), ocean acidification (which makes it harder for shell-building species to survive), migration of fish towards the poles (disrupting global fisheries), pollution and over-fishing are driving the ocean towards what some scientists see as a tipping point—not just for climate change, but for the ecology of the ocean itself.

What can we do, besides turn off our lights for an hour each year? Following on the meeting of Small Island Developing States (SIDS) in Apia, Samoa, last year, the voyage of the Hōkūleʻa—to raise awareness of the health of the oceans and therefore, of the Earth—has adopted the One Ocean, One Island Earth pledge. And we are all encouraged to do likewise. You can sign up for the pledge here. The pledge is simple:

- I recognize that Earth is a blue planet. Our ocean is the cornerstone of life, and our planet’s life-support system.

- No matter where on Island Earth I live, the ocean produces the air I breathe and helps to regulate the climate.

- I recognize that our ocean and Island Earth is changing because of the habits and choices of human beings.

- I recognize that with supporters like me, and the community I reach out to around me, the future of our oceans and our Island Earth can improve.

- The difference will start with me and spread to others. I pledge to support our oceans and Island Earth, and inspire people of all ages to do the same.

As the Polynesian voyaging canoe Hōkūleʻa circles the globe on its worldwide voyage, the crew seeks to find and share stories of hope that can bring us all together to care for the one ocean and the one island earth that we share. It takes a people from Oceania—who see the ocean not as empty space but as a dynamic realm much greater than land—to teach us the importance of caring for the oceans.

For those of us who grew up on the great land continents, and have always thought of the sea as something one ventures out onto once in a great while, and possibly with some hesitance, the sea is simply that great blue empty space. On many maps it is colored a uniform, solid blue. But for the people of Oceania, the sea is places, roads, highways. It is gods, and mysteries, and destinies. It is a medium that connects the small bits of land where people rest between journeys. And for all of humanity—indeed, all species of life on the planet—it is the Great Source.

Just as all rivers flow ultimately to the sea, so all of human activity is tied to the ocean, for better and for worse. For among the great metropolises of the world, the ocean is the dumping ground. It is where the polluted rivers flow, where the garbage ends up, where nuclear waste is stored. If you want to get rid of it, throw it in the sea. The sea is infinite after all, isn’t it?

What we now know is that human garbage is ending up in the deepest and most remote parts of the ocean. Just as our lands have absorbed the toxic by-products of industry and agriculture, and the atmosphere has absorbed the carbon dioxide and other gaseous and particulate output of smokestacks and exhaust pipes, so too the ocean—that great being that has always seemed capable of absorbing everything without consequences—shows many of the same sad signs of abuse. The lesson is clear: we can no longer thoughtlessly throw things “away.” There is no “away” anymore. Not even in the ocean.

In a previous article, I wrote how the Earth is like an island, and like a canoe (a large voyaging canoe, that is): what we have is all we have, and as we would do aboard ship, we must take care of the vessel that carries us, that we may survive and thrive. And strange as it seems, as we think about Island Earth, we must recognize that the ocean is part of that island too. Here I offer some thoughts in that regard.

In his book Thinking History Globally, Diego Olstein reminds us that “Oceanic histories transcend enclosed political and regional boundaries by privileging bodies of water rather than the terrestrial domains.” An oceanic perspective focuses on sea-borne connections between human societies. And with globalization, those sea-borne connections have become much greater. The sea that surrounds us, which Tongan author Epeli Hau’ofa wrote about, in talking of how the peoples of Oceania see the ocean as connecting, rather than separating, now holds true for the entire planet. The once-mighty continents themselves are now islands in the sea, and we who dwell on them should learn to understand them as such.

As climate change and other human-induced environmental issues increasingly close in on us, we are standing on the edge of a new journey forward: one that demands the best of us, the greatest wisdom, the wisest plotting of the course forward. Where the ancestors of Oceania’s peoples used painstaking observation of the oceanic elements, trial and error, commitment, determination and innovation to design vessels that could journey out into the unknown, so too do we now need deep vision and courage to visiualize a new beginning that will take us beyond the horizons set by the dominant worldview. As Tongan scholar Winston Halapua has said, “We need new ways of thinking and new ways to approach the huge challenges that confront us and will demand the best of all our energies and will be a deeply authentic way to journey forward.”

One Ocean, One Island Earth. The earth is the canoe taking us on our journey into the future. We are all in the same boat. And 70 percent of that “boat” is the ocean.

The Smithsonian Institution will participate in this year’s Earth Hour. Tonight the American Indian Museum, Air and Space Museum, Natural History Museum, National Zoo, Hirshhorn Museum, and Castle will go dark to show commitment to sustainability.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Doug-BPBM-2011.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Doug-BPBM-2011.jpg)