Vivid Images of Civil War Casualties Inspire a Scholar’s Inner Muse

Alexander Gardner’s photography, a record of sacrifice and devastating loss, prompts a new creativity from the show’s curator

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/75/fb/75fb53e3-1bf5-49f7-89dd-4ef907566102/completely-silenced-exh-ag-09web.jpg)

Antietam is my favorite battlefield because it is still largely unspoiled—it doesn’t have the huge number of memorials that dot Gettysburg and it is more pristine than Chancellorsville and the Wilderness, where roads, shopping malls and housing developments encroach on the sites. The landscape and the buildings here recall the 19th century—if you can ignore the automobiles—and a visitor is left to contemplate what happened on this otherwise peaceful, cultivated landscape on September 17, 1862—still known as America’s bloodiest day, when nearly 23,000 soldiers were wounded or lost their lives.

Occasionally as the land is worked or eroded by water, a corpse surfaces on the battlefield as it did one day in 1989, making headlines in the local press. The macabre story prompted me to write the poem: “On a Recently Discovered Casualty of the Battle of Antietam,” which was published in the Kentucky Poetry Review. It’s not a very good poem—verbally clunky—but I like the opening lines:

“Farm land, plowed land, shot plowed,/Now plowed again to uncover a biography.”

I’ve gone on to have modest success as a poet, but after that first Antietam work I have not written more than one or two “history” poems. I think my unconscious decision was that poetry is another part of my life, separate from my job as an historian. Recently though, I started writing poetry about the Civil War as I worked on the upcoming exhibition for the National Portrait Gallery, “Dark Fields of the Republic. Alexander Gardner’s Photographs, 1859-1872.”

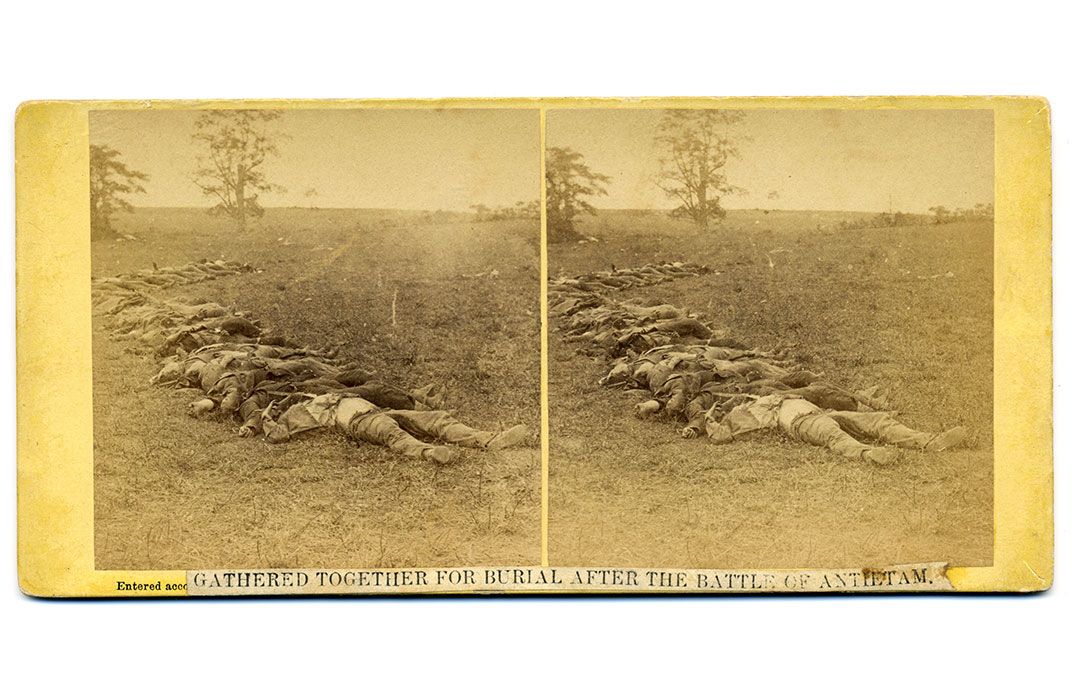

Gardner was one of the pioneering figures in creating documentary photography. Not only an excellent technician, he made his name by taking pictures of the Antietam battlefield soon after the fighting ended, and he left a cache of indelible images of the dead and the blasted landscape. When displayed to the public at a gallery in Manhattan, the New York Times wrote that Gardner’s photographs had “a terrible distinctness” and that the images brought the reality of modern war into the parlors and streets of the home front. It was a devastating moment for Americans as they saw the costs of war pictured so graphically and distinctly in the pitiless gaze of the camera.

BRADY’S STUDIO: “The Dead at Antietam”

Photographs of the battle

dead had a “terrible distinctness,”

horror fused in the clarity

of the new imagery

the gallery crowds

scarred yet flocking to it

unable to look away

the reality of war

the camera caught KIA

with pockets turned out

looted, shoes and socks stripped off

faces contorted

(We regret . . .your son

Maryland campaign. . .painlessly

. . .he didn’t suffer, at peace,

Sincerely, Col. . . . )

the old proprieties

dissolving in the acid of the new

the modern arriving, click of a shutter,

without warning

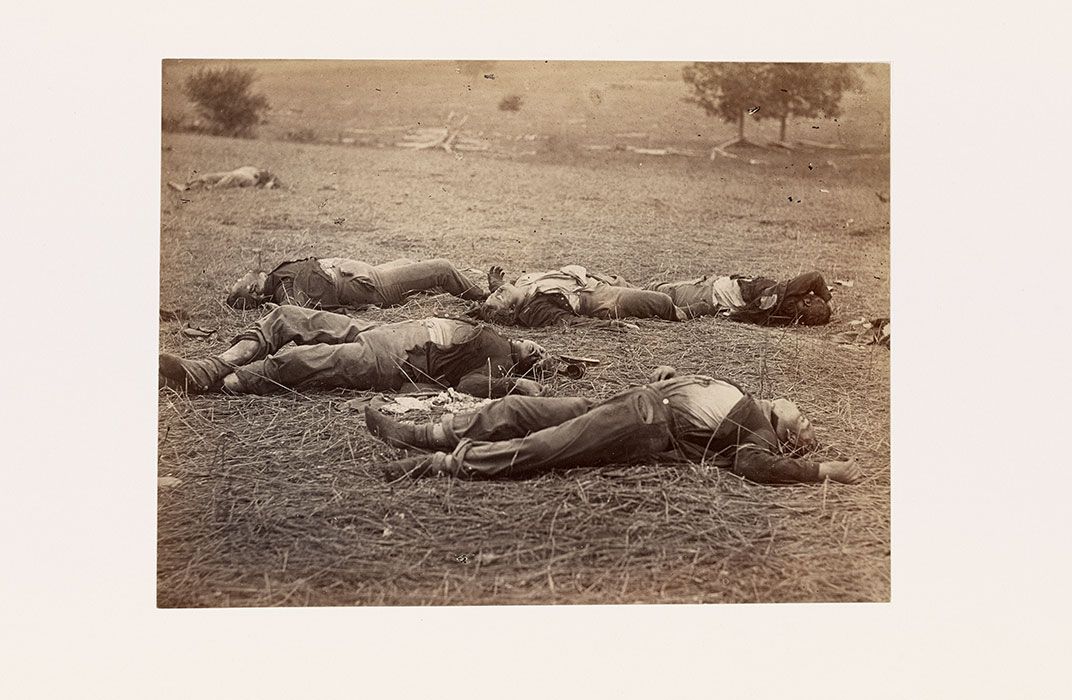

It was “the birth of the new,” not just for photography, but in the culture and society at large. The photographs contributed to the huge sea change in America with the onset of modernism in everything from manufacturing to literature. And the photographs influenced the course of the War itself. A year after Antietam, Gardner went to Gettysburg where he again documented the cost of battle.

BURIAL DETAIL, Gettysburg July 7, 1863

—more than 3,000 horses and mules were killed at the Battle of Gettysburg

it wasn’t the men

somehow you got numb to the bodies

blown apart, befouled and twisted

black like metal work

no, it was the horses

bloated in their caisson or wagon

traces, a dying struggle to get up

dead on their haunches

uncomprehending eyes frozen

bulging bewildered at what had fallen

on them shrieking

from a cloud of steel

no, it was the horses

that the Iron Brigade’s farm boy

veterans wept over as they pyred

them into a torch of smoke

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c2/88/c288d92e-0a64-4ed5-97d6-ed51ae15be40/npg_79_150-lincolnweb.jpg)

Gardner was Lincoln’s favorite photographer and the president must have seen the photographs of Gettysburg when he visited Gardner’s Washington studio in early November 1863, just before he went to the battlefield to help dedicate the cemetery. It is my supposition that the rhetoric of the Gettysburg Address was shaped in part by Lincoln’s photographic encounter of the battle dead. It is there in the chasteness of Lincoln’s language as well as in the appeal that “. . .we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract.”

WORD CLOUD OVER GETTYSBURG

The crowd, vaguely gathered

about the podium, what was next?

the President suddenly

doffing his tall hat, taking

a small paper from it, rising,

without introduction

or preliminary throat clearing,

the crowd distracted

barely noticing that tall figure

or hearing that reedy tenor,

the flat midwestern vowels, the words

and sentences cadenced,

cast out above them

promissory, floating up and into

then past the grey November sky,

arcing out above the earth bound

uncomprehending crowd

hearing only fragments, incomplete:

“cannot hallow. . .”, “last full

measure. . .,” “new birth. . .”

“of the. . .,” “. . people,”

“ by the. . . ,” “shall not perish,” “earth.”

Words uttered, flying, the President

suddenly sitting, proceedings

resumed, while unnoticed

far out and high, the words regathered

meaning, force, and fell back

to earth, seeding the dark fields.

It is this sense of hallowed ground that motivates my work on the first major retrospective of Alexander Gardner’s photography. Details of biography, history and photographic detail aside, the exhibition is called “Dark Fields of the Republic” because I want Gardner’s photographs to evoke for a modern audience what they did for 19th century Americans, including Lincoln, who saw them for the first time.

Gardner’s photographs are a record of the sacrifice and loss that occurred in the great national struggle over the Union and for American freedom. They are a graphic, documentary record of how heroism in history is as equally mixed with tragedy–and that all change entails loss along with the gains. In the ceaseless workings of American democracy, the sacrifice that Lincoln noted is indelibly imprinted not just in his words, but in the photographs of Alexander Gardner: “That from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain.” The battlefield exerts its gravitational pull both on myself and, whether knowingly or not, on all Americans and our history.

“Dark Fields of the Republic. Alexander Gardner’s Photographs” opens at the National Portrait Gallery on September 17, 2015–the 153rd anniversary of the battle of Antietam, the battle that permitted Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation and so change the nature and consequences of the Civil War.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)