Touring the Tools of Civil War Medicine

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20110725034003civil-war-medicine.jpg)

The discovery of anesthesia dates to right around 1842, says Judy Chelnick, a curator who works with the medical history collections at the National Museum of American History. But at the start of the Civil War in 1861, effective techniques of administering drugs such as ether had not yet been perfected. Many patients may have died from receiving too much ether, Chelnick says, while others woke to experience the painful procedure.

Chelnick is standing in a room full of fascinating objects behind an exhibition on the third floor of the museum. It’s a place few tourists ever get to see, but the tools we’re discussing will be on display for visitors attending the Resident Associate program’s Civil War Medicine at the American History Museum event tomorrow, July 26.

I ask about a scary-looking curved metal tool with a sharp point.

“What’s that for?”

“You don’t want to know,” Chelnick responds.

She explains, but it turns out that no, I really didn’t want to know that that tool was used for puncturing the bladder directly through the abdomen to relieve pressure on the organ. I cringe involuntarily. Yes, I could have done without that knowledge.

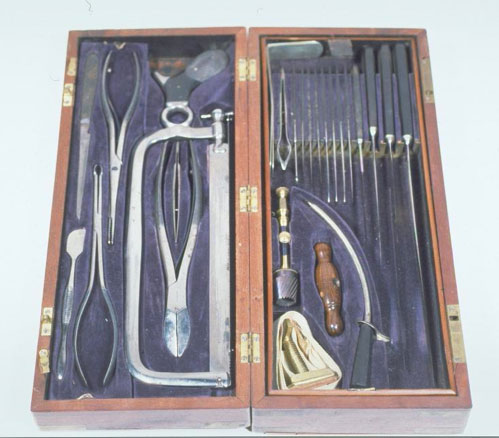

As we continue our survey of the tools, most of which are still surprisingly shiny but have old wooden handles (“This was before germ theory,” Chelnick says), we come across many other objects that you probably don’t want to see in your next operating room. A brutal-looking pair of forceps that Chelnick says were used for cutting bone, some saws that look just like the ones I used in wood shop in high school and a terrifying object slightly reminiscent of a drill that was used to bore holes in the skull.

The sets of tools are incongruously packaged in elegant wooden boxes with red and purple fabric lining that I suspect is velvet. I can’t help thinking that those are good colors, because blood probably wouldn’t stain too badly.

Chelnick lifts up a tray of knives in one of the kits, and reveals something really amazing. It’s a set of cards, matriculation cards, Chelnick says they’re called, belonging to the doctor who owned this particular set. They’re from his time in

Surgical kit made for the Union Army during the Civil War by George Tiemann & Company of New York City. Courtesy of National Museum of American History, Kenneth E. Behring Center

medical school (only two years were required back then), and they list his name (J.B. Cline) and the classes he took. It seems that Dr. Cline studied chemistry, diseases of women and children, pharmacy, anatomy and surgery, among other topics. For the sake of the Civil War soldiers he treated, I’m glad this was an educated man, but I still wouldn’t let him near me with any of those knives.

All in all, it’s enough to make anyone uneasy, but Chelnick says that’s part of the point.

“I think that a lot of times people have a romanticized vision of the war in their head,” Chelnick says. “And so I think the medical equipment really brings out the reality of the situation. It’s a reminder that there are consequences–people got hurt, people got killed.”

She adds that gunshot wounds and other battle injuries were not even close to the greatest killers during the Civil War. Rather, most fatalities occurred from diseases or infection spread in the close quarters of military camps.

I point out another tool in one of the kits. Chelnick restates what has become a frequent phrase in our conversation: “You don’t want to know.”