Studying Bacon Has Led One Smithsonian Scholar to New Insights on the Daily Life of Enslaved African-Americans

At Camp Bacon, a thinking person’s antidote to excess, historians, filmmakers and chefs gather to pay homage to the hog and its culinary renown

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8c/15/8c152946-b335-465f-88c0-9ca3e7499146/pork-processing-at-wessyngtonweb.jpg)

In Ann Arbor, Michigan, during the first week of June, an annual event unfolds that honors the culinary delights and history of perhaps the nation’s most beloved food—bacon.

Bacon has long been an American staple of nutrition and sustenance that dates to the arrival of the Spanish Conquistadors with the introduction of pigs to the hemisphere, but it has never created more excitement than it does today.

At Zingerman’s Cornman Farms and other locations around Ann Arbor, the company’s co-founder Ari Weinzweig hosts a week of festivities for a five-day celebration dubbed Camp Bacon that attracts some of the most ardent pork aficionados and supporters along with a host of filmmakers, chefs and culinary historians.

Weinzweig created Camp Bacon as a thinking person’s antidote to the bacon excess seen at events like Baconfest that arose in his native Chicago, where ironically he grew up in a kosher household. Springing from Weinzweig’s argument, detailed in his book Zingerman's Guide to Better Bacon, that bacon is to America what olive oil is to the Mediterranean, this eponymous happening is now the Ted Talks of yes, bacon.

And this year, I am proud to be one of the speakers. I will arrive hungering for the smokey, savory and sensual ambiance. But besides my fork, I come armed with the footnotes of history to tell a story of the culinary myths and practices of enslaved African-Americans, like Cordelia Thomas, Shadrock Richards and Robert Shepherd, held in bondage on the plantations of the South Carolina Lowcountry and the Georgia coast.

Sadly in our nation’s history—erected on a foundation that included slavery—even bacon can be tied to bondage, but we will celebrate still the achievements of the bondsmen and women as culinary creators.

For Cordelia Thomas, excitement was in the air as the Georgia weather began to turn crisp and cool one December just before the Civil War. On cool evenings as she lay awake on the cramped cabin floor, sounds echoing out of the piney woods and across the rice bogs foretold what was to come. Dogs barked and bayed, men shouted and whooped, pots and bells clanged, and hogs squealed.

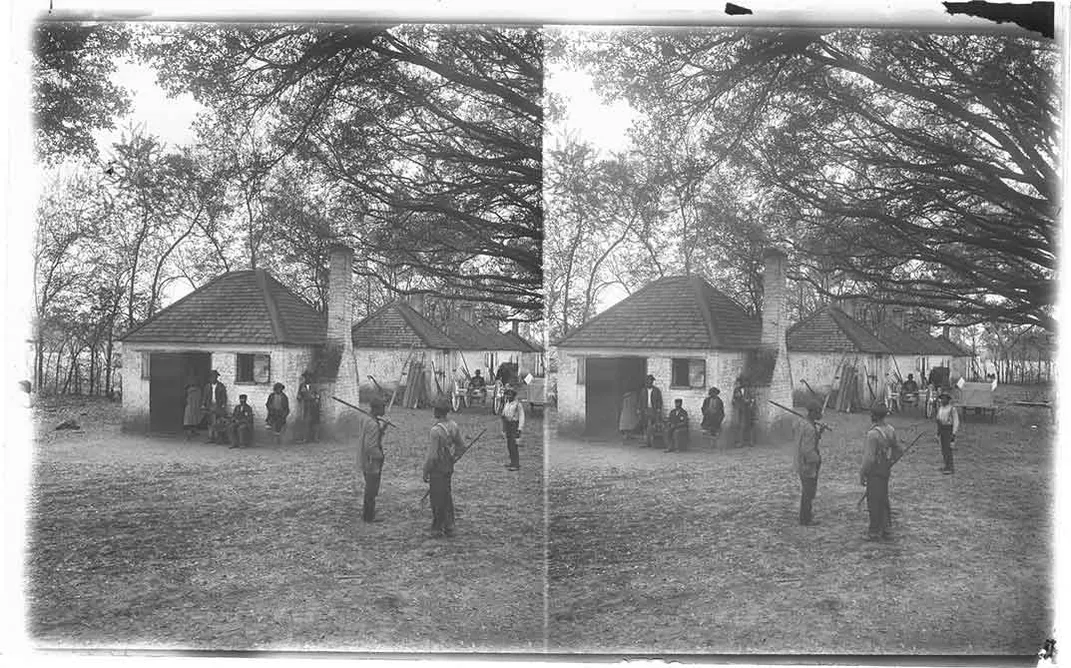

Killing time was approaching and the men and boys from the plantation where she and her family were held in bondage went out to round up the hogs that had been foraging unfettered through the upland woods and down into the swamps. They were last rounded up in early summer so the shoats could be marked the plantation’s distinctive earmarks. Now dogs and men corner the hogs, and those with the right cut marks on their ears were brought back to pens on the farm.

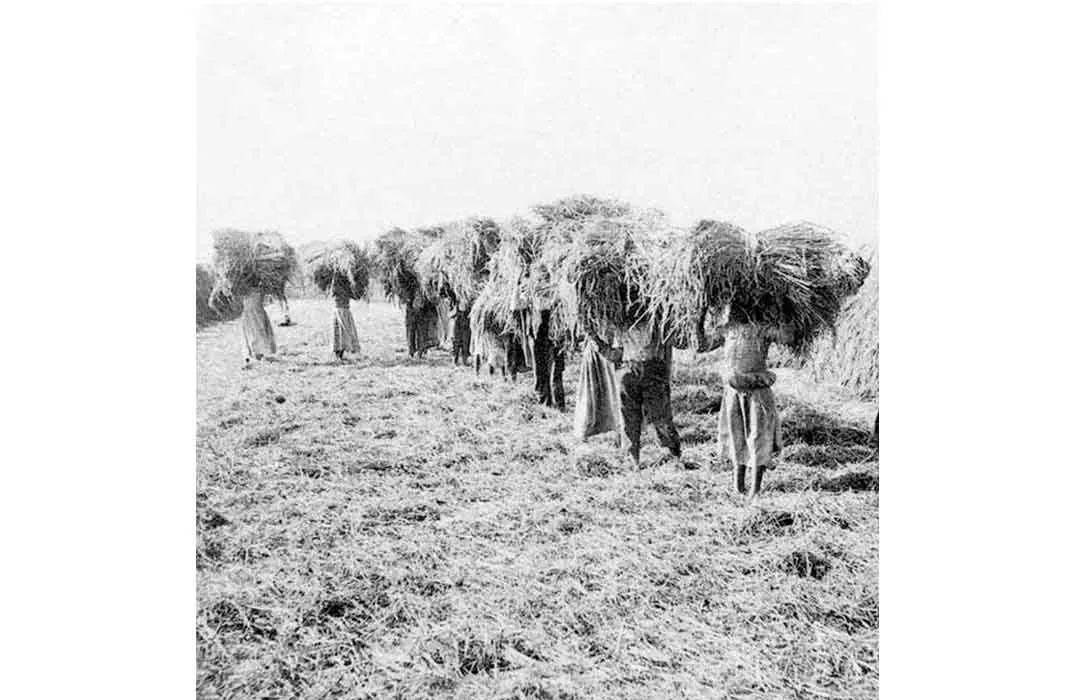

On big plantations in the Lowcountry, killing time was serious work, just like everything else in these forced labor camps. Hundreds of hogs had to be slaughtered and butchered to provide the 20,000 or 30,000 pounds of pork it might take to sustain the enslaved workers toiling all year to produce rice and wealth for the few, incredibly rich white families of the region.

Mostly hogs were used as a way to extract resources from the surrounding wilderness without a great deal of management. The “piney woods” hogs of the region, which most closely resembled the rare Ossabaw Island breed, were left to fend for themselves and then, as depicted in the film Old Yeller, with the help of good dogs hunted down and subdued either for marking or slaughter.

In public history on the subject of slavery, there is always a conflict in how the story is presented—we often choose between presenting the story as one of oppression vs. resistance, subjugation vs. survival, property vs. humanity.

Because the legacy of slavery is still so contested, audiences are sharply critical of presentation. If one shows a story of survival, does it follow then that oppression is given short shrift? If, on the other hand, we focus on brutalization, we run the risk of suggesting our enslaved ancestors were defeated by the experience of slavery.

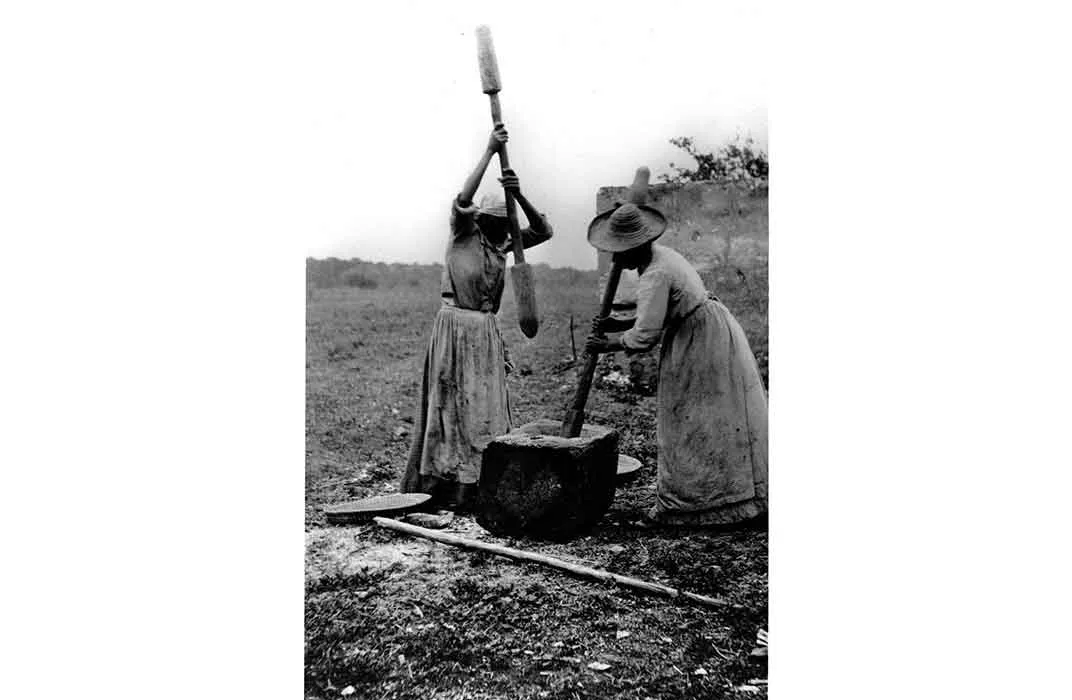

This conflict is certainly at work in how we remember food on plantations. Missing from the common understanding of pork on the plantation though, is the skill of the enslaved butchers, cooks and charcutiers.

The work involved young men like Shadrack Richards, born into slavery in 1846 in Pike County, Georgia, who remembered more than 150 people working for over a week on butchering and curing, preserving the sides of bacon and shoulders and other cuts to keep on the plantation and taking time to create great hams for sale in Savannah. Another survivor of slavery Robert Shepherd remembered with pride just how good the hams and bacon were that his fellow butchers created despite the cruelty of slavery. “Nobody never had no better hams and other meat” than they cured, he recalled.

Cordelia Thomas looked forward to killing time all year. Living in Athens, Georgia, when she was interviewed by the 1935 Works Progress Administration endeavor known as the Federal Writers Project, at age 80, she recalled: “Children was happy when hog killing time come. Us wasn’t allowed to help none, except to fetch in the wood to keep the pot boiling where the lard was cooking.”

She remembered rendering the lard in big washpots set on rocks over a fire, and she didn’t mind at all being tasked with gathering the wood for that fire “because when them cracklings got done they let us have all us could eat.”

“Just let me tell you, missy,” she said to her New Deal interviewer, “you ain’t never had nothing good less you have ate a warm skin crackling with a little salt.”

Thomas also relates that the rare treat of cracklings was so enticing that all the children crowded around the rendering pot. Despite warnings from the planters and elders in the slave community, she fell into the fire after she was pushed by another child. Thomas, who said she had to keep her burnt arm and hand in a sling for a long time after that, remembered the planter “laying down the law” after that as he threatened what he would do if the slave children, his valuable property, crowded around the lard pot again.

From this oral history, we learn that enslaved African Americans found some joy in small things—we can relate to the flavor of cracklings at butchering time and the opportunity to eat your fill. And farm life in the 19th-century was hazardous—accidents with fires were only slightly less deadly than childbirth and disease, but those dangers were elevated by the cruel nature of plantations as crowded work camps. And, in the end, human concerns for health, happiness and safety were absent, as profit and labor reigned supreme.

One of the things we consider and study in the museum field is the relationship between history and memory.

“History is what trained historians do,” wrote the renowned Yale University scholar David Blight, “a reasoned reconstruction of the past rooted in research; it tends to be critical and skeptical of human motive and action, and therefore more secular than what people commonly call memory. History can be read by or belong to everyone; it is more relative, contingent on place, chronology, and scale. If history is shared and secular, memory is often treated as a sacred set of absolute meanings and stories, possessed as the heritage of identity of a community. Memory is often owned; history is interpreted. Memory is passed down through generations; history is revised. Memory often coalesces in objects, sites, and monuments; history seeks to understand contexts in all their complexity. History asserts the authority of academic training and canons of evidence; memory carries the often more immediate authority of community membership and experience.”

All this to say that memory, even public, collective memory, is faulty, that we chose what we wish to remember and that we construct the narratives that we want to share of our lives. My colleague at the Smithsonian, Lonnie Bunch, founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Cuture, set to open on September 24, often says the new museum is about helping people remember what they want to remember, but making people remember what they need to remember.

As historians, we study and research the past and we write the complex narratives of the American story, but in the public sphere, whether at a museum or in a film, TV show or popular magazine article, there is an expectation of answers that reflect some of the textbook myths that we’ve come to use to understand and interpret the past. These “myths” are not entirely untrue either—they are the long-held historical truths that we hold in common as part of our understanding of our shared past.

There are, of course, history myths like George Washington and the cherry tree or the story we all know of the Pilgrims and the first Thanksgiving, which are either partially or totally untrue. But there are history myths that everyone knows and our understanding of that story is largely historically accurate. I worked at the Henry Ford Museum when it acquired the very bus that is the singular element of the Rosa Parks story. We all know that story well and with relative accuracy.

Over the 30 years I have been involved in public history, one subject that has acutely demonstrated how history and memory can be at odds, and even conflict, is slavery.

This is true for many reasons. First, the evidence is problematic—most written records are from the point of view of the slaveholder and the oral histories of people who experienced slavery like Cordelia Thomas can be difficult to interpret.

Interpretation of slavery’s history has always been associated with power. In the same way that the institution of slavery was imbued with issues of power, our memory of it is as well.

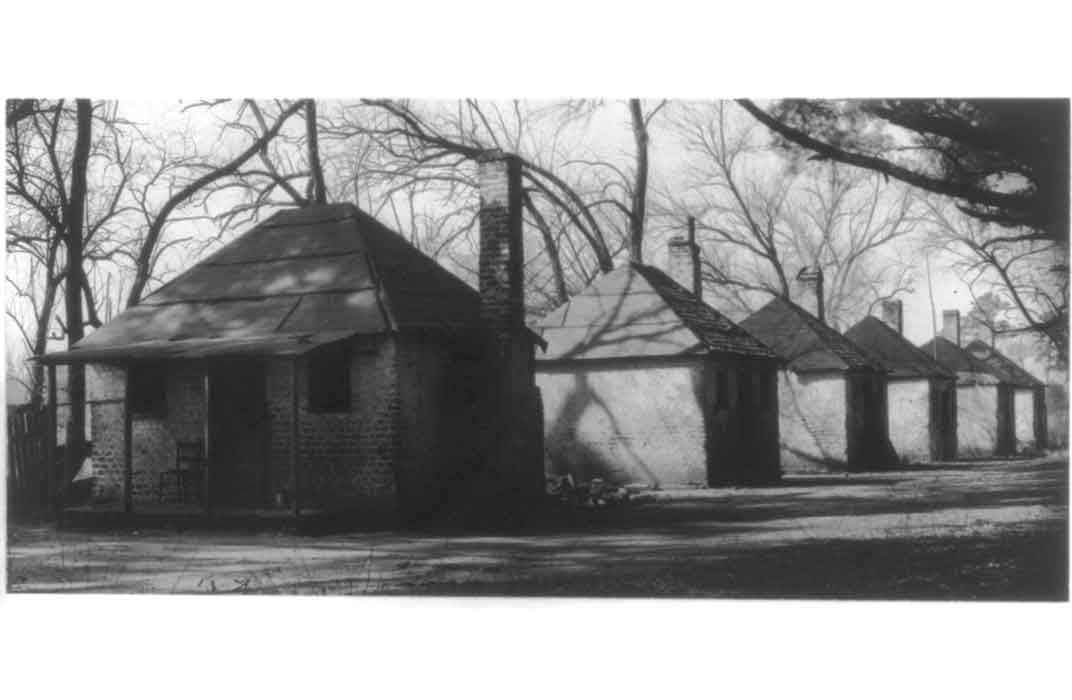

I came head to head with these issues when we began to explore the history of slavery in Lowcountry Georgia at the Henry Ford Museum in the early 1990s. We restored and reinterpreted two brick buildings that housed enslaved families on the Hermitage Plantation from Chatham County, Georgia, just outside Savannah and in the “kingdom of rice.”

As we began to outline how we would present one story of slavery, we ran squarely into what Blight called “sacred sets of absolute meanings.” The decisions we faced of what to call the buildings—“houses,” rather than “quarters” or “cabins,” or to concentrate on family life and culture rather than work and oppression, these very decisions were laced with power and authority; and sometimes ran contrary to what the public wanted from an exhibit.

This became clear when I trained the first group of staff to work in the slave houses to present and discuss this traumatic history to visitors. Many visitors came with expectations. They wanted simple answers to complex questions, and in many cases they wanted confirmation of memories that they had of their grade school history lessons. “Slaves weren’t allowed to read and write, right?” “Slavery was only in the South, wasn’t it?” Or, sadly, quite often they would make the observation: “These buildings are pretty nice. I’d like to have a cabin like this. It couldn’t have been that bad, could it?”

This was certainly the case when we discussed food. It didn’t take long in discussing food on a Lowcountry rice plantation for me to encounter the public’s mythic misunderstanding of the origins of “soul food.” The master took the best parts of the pig, and the slaves were left with pig’s feet and chitlins, we commonly believe.

In some ways this story meshed perfectly with some of the themes we wanted to present—enslaved African Americans were oppressed, but undefeated. They took what they had and made due, creating a culture and keeping their families together against great odds.

But as with so much of the story of life on a rice plantation, the particular details of this unique region were not commonly known and did not wholly conform with our shared understanding.

Rice plantations were distinctive in a number of ways. First off, they were rare. The famous Carolina Gold rice—which has been brought back to life and dinner tables by artisan entrepreneur Glenn Roberts and his company Anson Mills—grown in the 19th century required tidal action to move massive amounts of water in and out of rice fields. Rice, however, can only take so much salt, so the fields can’t be too close to the ocean or the salinity will be too high. They can’t be too far away either because tidal waters must sluice through the fields several times each growing season.

Under those conditions, rice could only be grown in a narrow strip of land along southern North Carolina, coastal South Carolina, coastal Georgia, and a bit of northern Florida.

Historian William Dusinberre estimates that in the late 1850s, “virtually the whole low-country rice crop was produced on about 320 plantations, owned by 250 families.”

And rice plantations were big. Despite what we see in popular interpretations of slavery from Gone with the Wind to this summer’s remake of "Roots," the typical portrayal was one of small farm living with a few enslaved workers. About one percent of slaveholders in the South owned more than 50 slaves, but it was typical of rice planters to hold between 100 and 200 people in bondage, sometimes more. At the start of the Civil War in South Carolina, 35 families owned more than 500 enslaved African Americans and 21 of those were rice planters.

As I began to contemplate peculiarities of rice plantations like these and to cross-reference that with our commonly held myths of slavery, I began to see conflicts in that story. This was especially so with the “the master took the hams and chops and the slaves ate the chitlins” story.

Across the rice-growing region, the ration of pork for enslaved people was three pounds a week per person. On plantations like the Hermitage, where more than 200 people were enslaved, that would require slaughtering more than 200 hogs to produce some 30,000 pounds of pork.

It doesn’t stand to reason that the white planter family would eat all the “high on the hog” parts, because there would just be too much (although some plantations did send hams and bacon to cities like Savannah or Charleston for sale). Furthermore, due to the malaria and general pestilence and the oppressive heat of the lowcountry in the 19th century, white families generally left the plantation for the half of the year they called “the sickly season,” leaving only the enslaved and a few overseers there to work the rice.

At least in the Lowcountry rice plantations, the conventional view of what slaves ate doesn’t stand up to evidence. It also doesn’t stand up to the science and traditional methods of food preservation. Offal like chitlins and the cracklings Cordelia Thomas loved were only available right at killing time and couldn’t be preserved throughout the year.

What does ring true about the mythic interpretation of soul food is that it was one of the only times of the year when enslaved people could experience the joy of excess. In the reminiscences of the men and women collected by the WPA slave narrative project, hog killing time arises over and over as a joyous memory.

It’s likely no coincidence that butchering is also remembered so fondly given it took place near Christmas, when the enslaved were given time off from work in the rice fields. But it’s probably more due to the feast that occurred. Certainly killing, butchering and curing scores of hogs was a great deal of work for the whole slave community, but it also created a festive atmosphere where men, women and children normally driven hard to produce wealth for the rice planters could eat to their heart’s content.

Where the conventional “soul food” myth does ring true on Lowcountry plantations is that enslaved people were generally allowed to prepare for themselves all the excess pork that couldn’t be preserved. In other words, the enslaved community was “given” all the pork parts that the “master didn’t want,” but that wasn’t necessarily all they were allowed to eat.

Despite the fact that in the Lowcountry enslaved African-Americans were not solely eating the leftover, unwanted parts of the pig, that doesn’t mean they were living “high on the hog.” There is disagreement among scholars on the level of nutrition for bondsmen and women throughout the south, as well as in the rice growing region. Even the testimony of former slaves varies, with some saying they always had plenty to eat and others recounting malnourishment and want.

At a conference at the Smithsonian in May 2016, Harvard historian Walter Johnson said, “It is a commonplace in the historical literature that slavery “dehumanized” enslaved people.” Johnson went on to admit there are “plenty of right-minded reasons for saying so. It is hard to square the idea of millions of people being bought and sold, of sexual violation and natal alienation, of forced labor and starvation with any sort of ”humane” behavior: these are the sorts of things that should never be done to human beings.” By suggesting that slavery, Johnson continued, “either relied upon or accomplished the “dehumanization” of enslaved people, however, we are participating in a sort of ideological exchange that is no less baleful for being so familiar.”

Slaves and slaveowners were human. Slavery depended on human greed, lust, fear, hope, cruelty and callousness. To remember it as an inhuman time positions us incorrectly in a purer, more moral moment. “These are the things that human beings do to one another,” Johnson argued.

When I think of killing time on a plantation like the one on which Cordelia Thomas lived 150 years ago, I think of people reveling in the taste of expertly prepared food they put their heart, soul and artistry into. The taste of the cracklings around the rendering pot, or the anticipation of cowpea gravy with fat bacon during the steaming Georgia summer, was one way black families in the Lowcountry exercised control over their lives in the midst of the ruthlessness of the central moral event of our nation.

On the isolated coastal Carolina and Georgia plantations, enslaved women, men and children more than persevered, subsisting on scraps. They survived. In the same way that they demonstrated great skill and effort preserving every part of the pig except the squeal, they created their own language, music, art and culture, all the while sustaining families and community as best they could under the worst of conditions.

As we feast at Camp Bacon on some of the recipes that would have been familiar to people like Thomas, Richard, and Shepherd, I will reflect on the pleasure of great food tinged with the bitter taste that must have lingered for those in servitude.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kegley140407Wilson0014.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kegley140407Wilson0014.jpg)