Sam Kean Decodes DNA’s Past

The author discusses his new book, a collection of entertaining stories about the field of genetics titled The Violinst’s Thumb

Sam Kean’s first book on the periodic table of elements won rave reviews. He’s at it again with a book on the history of genetics.

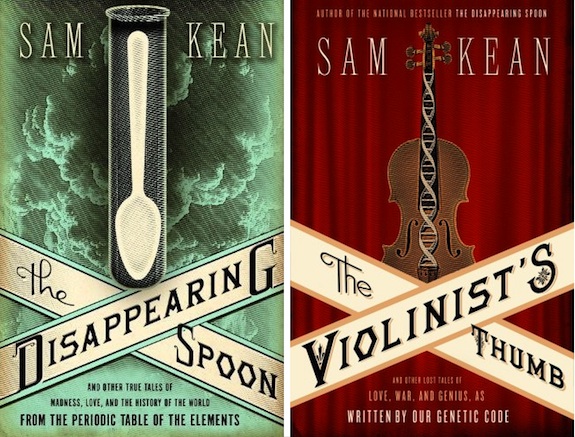

Sam Kean entertained readers with his first book, New York Times best seller The Disappearing Spoon, offering tales of discovery and intrigue from the world of the periodic table. His follow up, The Violinist’s Thumb, takes the same approach to the headline-grabbing field of genetics. Kean will be discussing both at the Natural History Museum Thursday at noon.

“I knew the human genome was a big enough topic to find a lot of great stories,” Kean says. A field whose history has seen its share of controversial theories and horrific as well as awe-inspiring applications, genetics did not disappoint.

For example, Kean mentions polar bears who happen to have an usually high concentration of vitamin A in their livers. Dutch explorer Gerrit de Veer first recorded the toxic effects of eating polar bears in 1597. Voyagers to the Arctic, when finding themselves stranded, hungry and staring down a polar bear, knew that a meal was at hand. “They end up eating the polar bear liver,” which, Kean says, doesn’t end well. Your cell walls begin to break down, you get bloated and dizzy. Not to mention, “It actually makes your skin start to come off, it just peels off your body, partly because it interferes with skin cell genes,” says Kean. A notoriously horrific genre anyway, polar exploration proved fertile ground.

Kean had his own DNA submitted for testing, thinking he’d find “some funny gene.” Instead, he got a lesson in the nature of genes.

Kean’s anecdotal approach to chemistry and now genetics has been hailed as a diverting, sneaky way to introduce readers to science, but he points out, it also useful for scientists to learn the history of their field. “I think it makes you a better scientist in that you’re a little more aware of what your work means to people, how other people view your work,” Kean says.

DNA research in particular can feel, well, so scientific, but Kean highlights the dramatic and personal connections. He came to this realization after submitting his DNA for testing. “I admit, I kind of did it on a lark,” he says. “But there were a few syndromes or diseases I found out I was susceptible too and it was sort of scary to face that because there was a history of that in my family. It brought back some bad memories,” Kean recalls. In the end, the testing episode also provided a valuable lesson for the rest of the book.

“The more I looked into it,” says Kean, “the more I realized genes really deal in probabilities, not certainties.” So while scientists are learning more about the influence genes can have on specific personality traits, we’re also learning about the role of the environment on DNA. The classic nature versus nurture split no longer holds true.

For example, identical twins have the same DNA. “But if you have ever known identical twins, you know that there are differences, you can tell them apart,” says Kean. That led Kean to his chapter on epigenetics, which examines how environmental factors can switch on or off or even amplify gene expression.

Nicoló Paganini, the eponymous violinist, was considered one of the greatest performers of all time because of his “freakishly flexible fingers.” He could do all sorts of parlor tricks with his unusual fingers and his performances in the early 19th century were so inspired that his audiences were said to burst into tears. One man, allegedly driven mad by the Italian musician’s virtuoso, swore he saw the Devil himself helping the violinist.

Satanic involvement aside, Kean says it all comes down to DNA. “It allowed him to write and play music that other violinists simply couldn’t because they didn’t have the same kind of hands.”

Check out notes, games and more extras from The Violinist’s Thumb here.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)