Raise a Glass to the Smithsonian’s First Beer Scholar

Theresa McCulla is ready to start the “best job ever” chronicling the history of American brewing

A little more than two decades ago, the American beer market was almost completely dominated by a singular type brew—something light, usually in a can, and originating from the Midwest. The monopoly of taste was so strong that by the end of the 1980s, industry experts predicted that eventually only five beer companies would be left in the United States.

That didn’t happen—instead, a coalition of craft brewers and homebrewers staged a beer revolution, changing the way that American consumers think about beer—one deeply hopped IPA or sour Belgian-style ale at a time. Today, with more than 5,000 breweries operating in the United States, craft brewing is booming. The sale of craft beers has doubled from $5.7 billion in 2007 to $12 billion in 2012.

It’s that changing landscape—as well as how beer has shaped American history throughout the 19th and 20th centuries—that Harvard scholar Theresa McCulla takes a seat overseeing the Brewing History Initiative at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. McCulla’s position, dubbed the “best job ever” by Washingtonian magazine is supported by the Brewers Association, a nonprofit trade group representing brewing professionals, which seeks to expand the Smithsonian’s understanding of the role beer has played—and continues to play—in American history.

“Smithsonian has already used food as a very critical and successful entry point into talking with the public about much bigger questions relating to American history,” says McCulla. “We really feel quite strongly that beer is a very effective lens into much bigger questions about American history. If you look at the history of beer, you can understand stories related to immigration and industrialization and urbanization. You can look at advertising and the history of consumer culture and changing consumer taste. Brewing is integrated into all facets of American history.”

McCulla comes to the position with a background in social history and food; she holds a culinary arts diploma from the Cambridge School of Culinary Arts’ Professional Chefs Program, directed the Food Literacy Project for Harvard University Dining Services, and managed Harvard’s two local farmers markets from 2007 to 2010. She will receive a doctorate in American Studies from Harvard University in May of this year. But this is McCulla’s first time studying beer exclusively—and she has already hit the ground running, spending her first few weeks on the job combing through the museum’s extensive collections to see what beer-related materials the Institution already has on-hand.

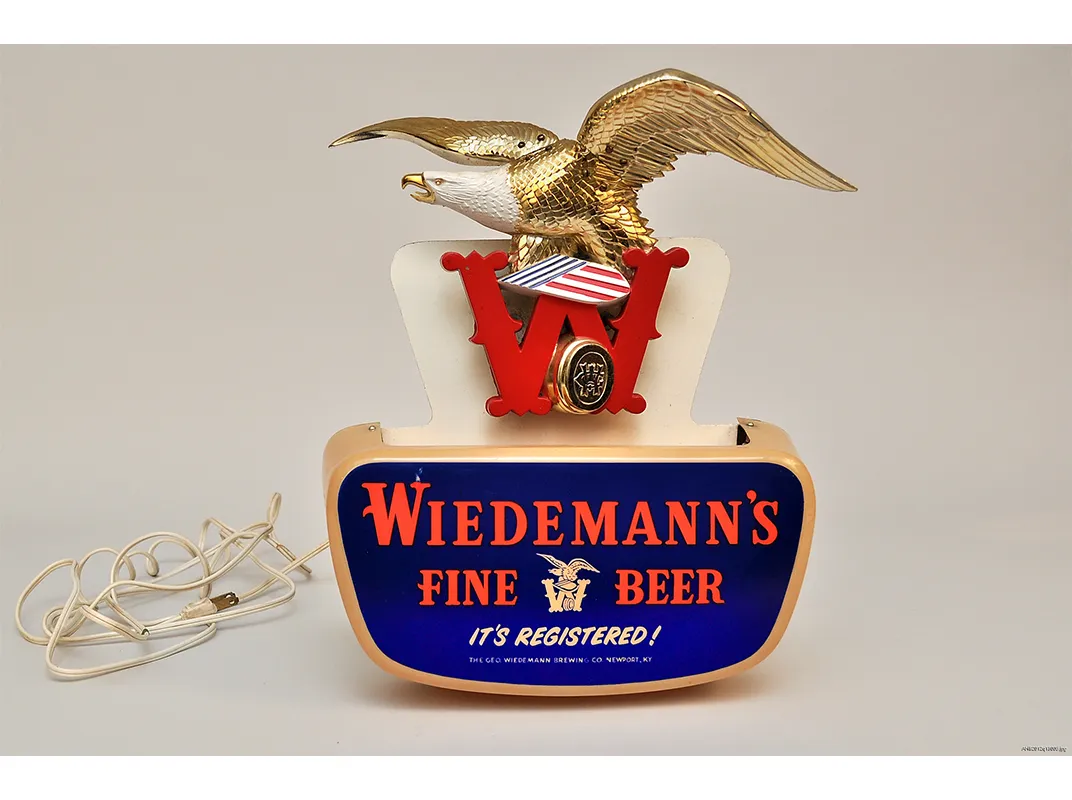

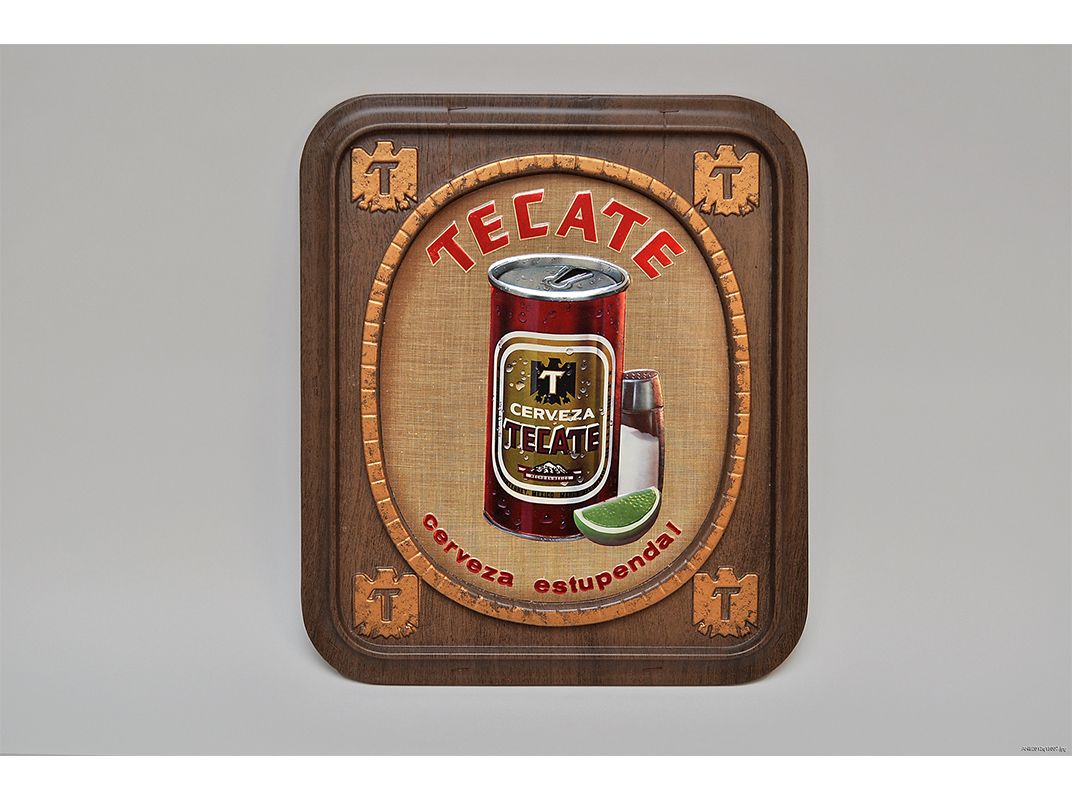

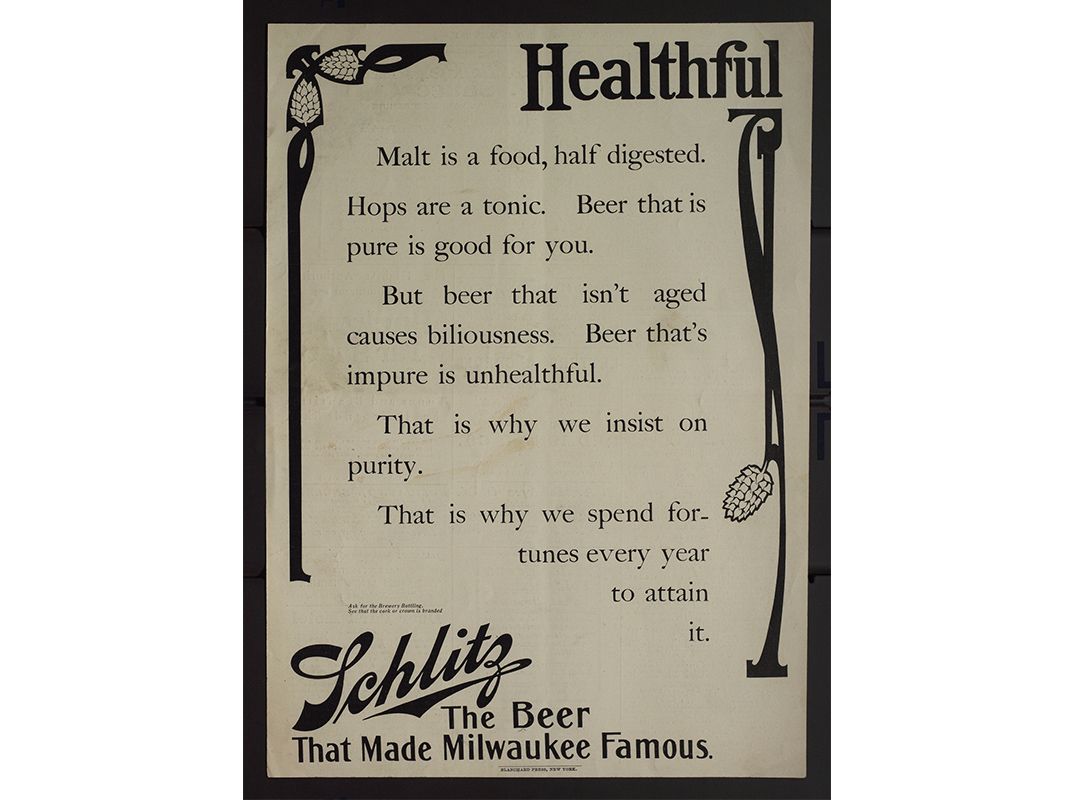

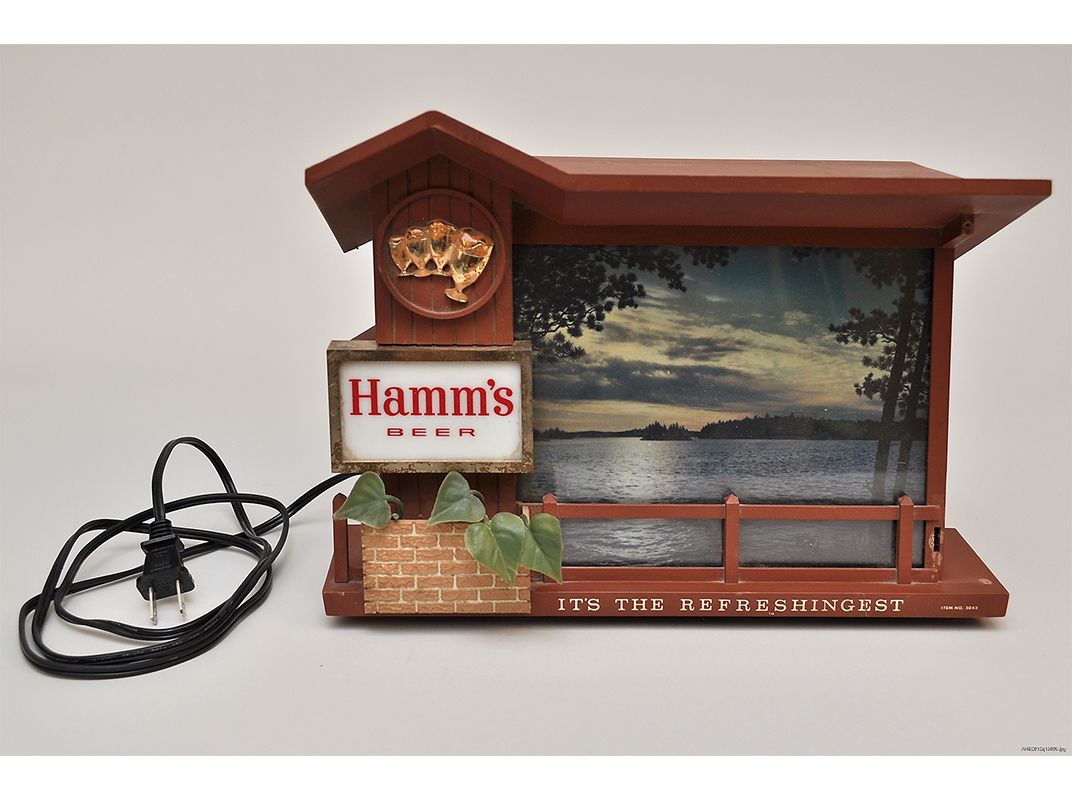

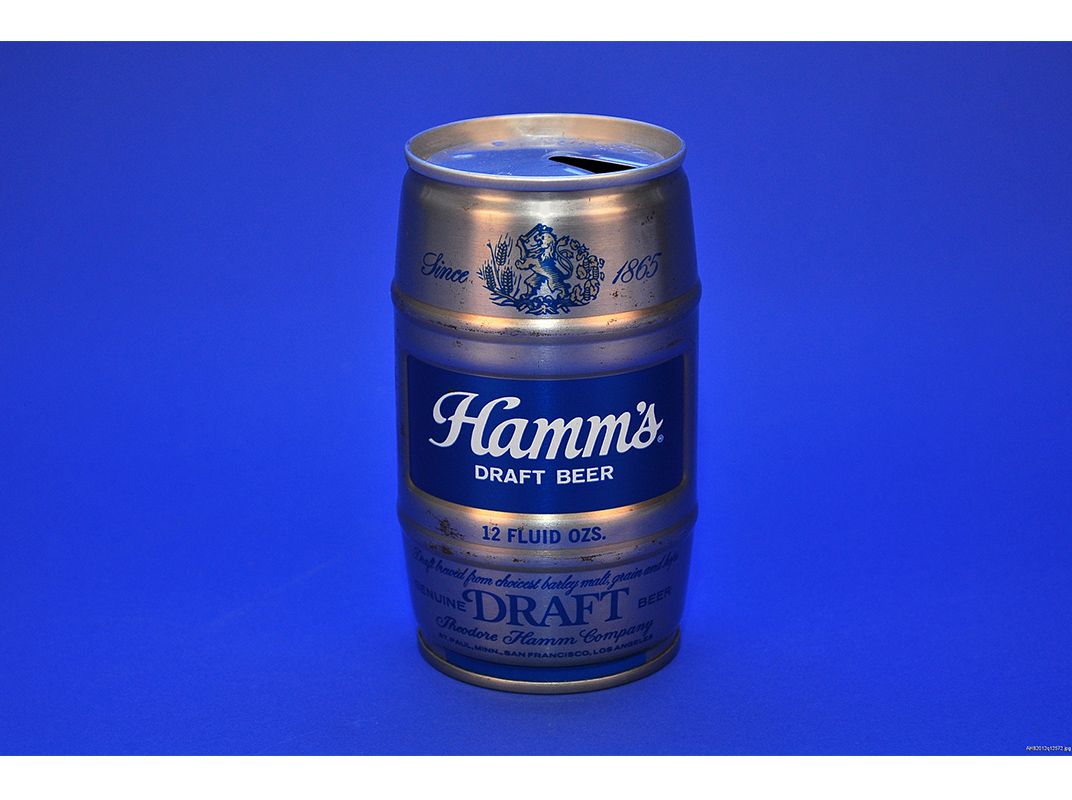

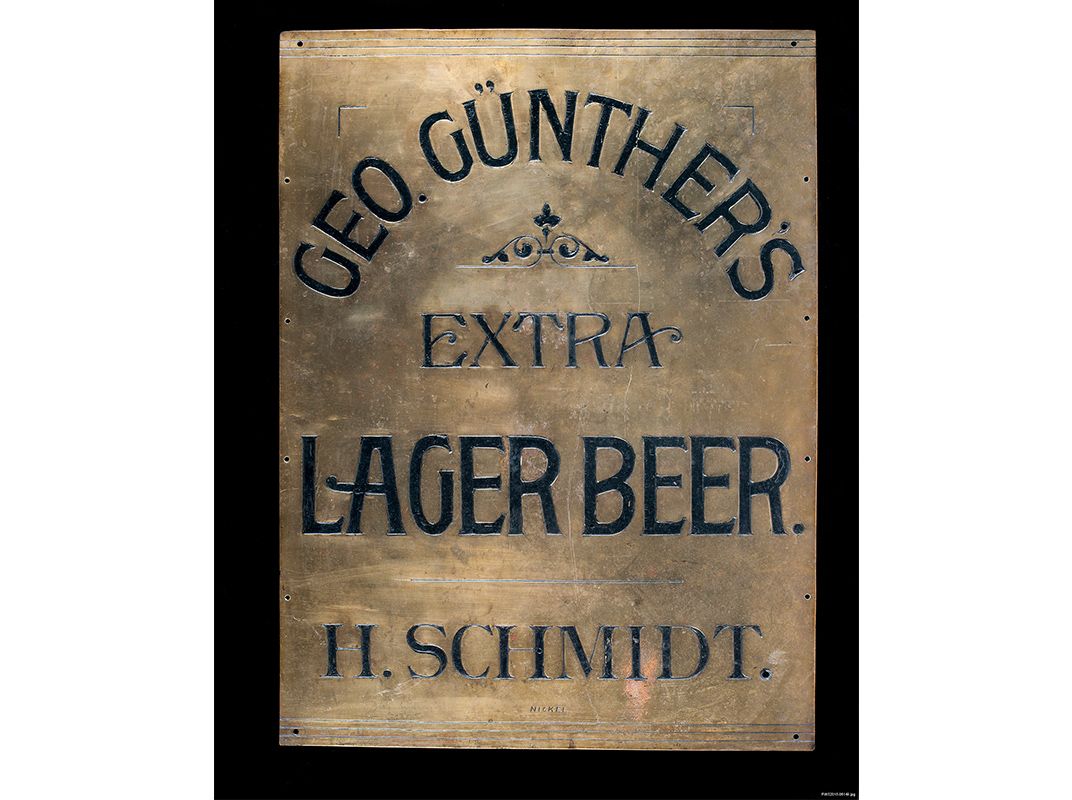

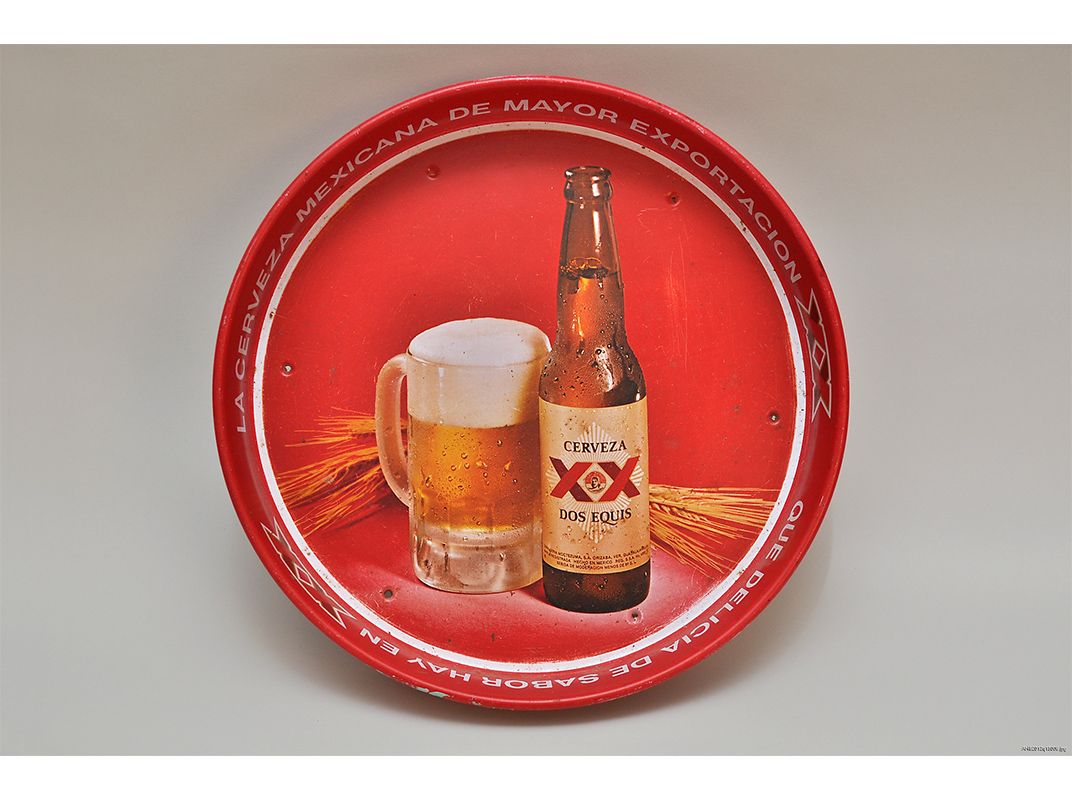

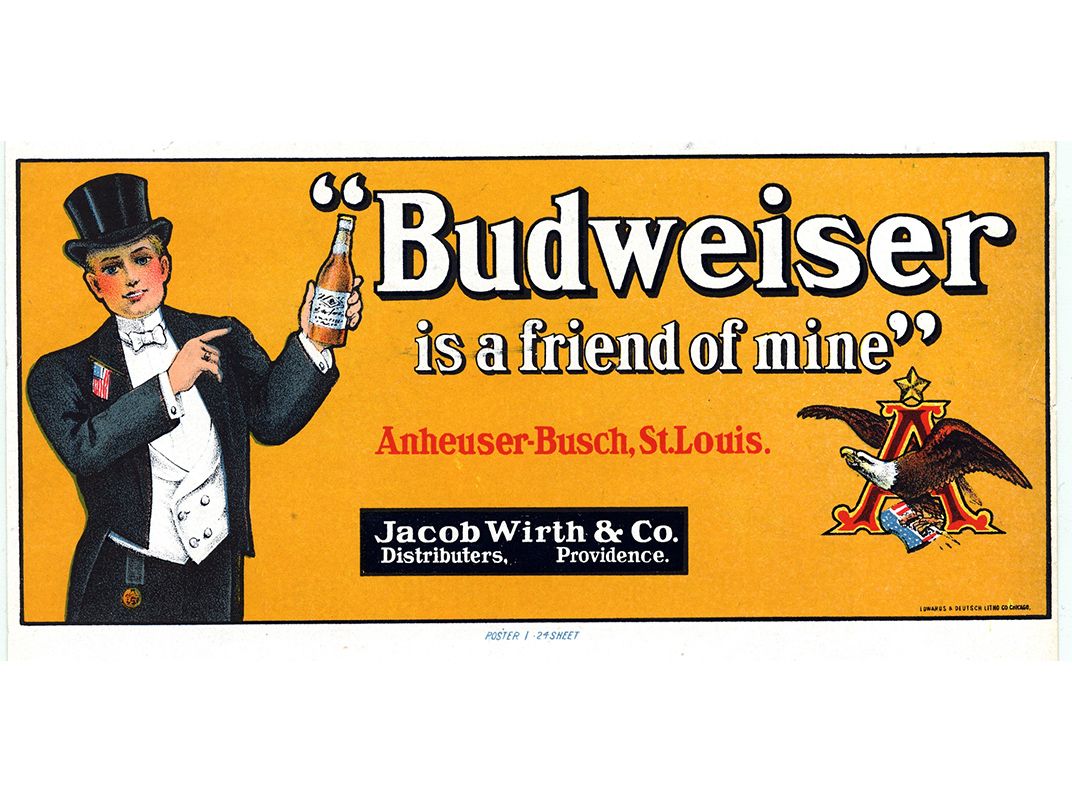

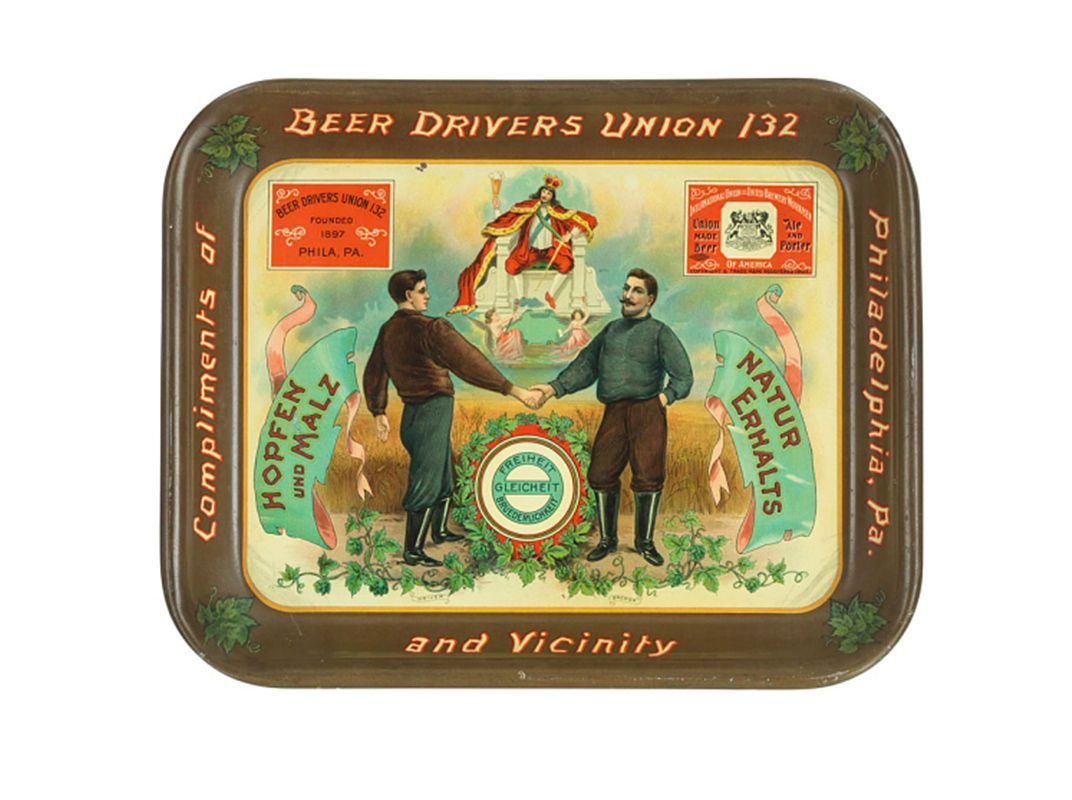

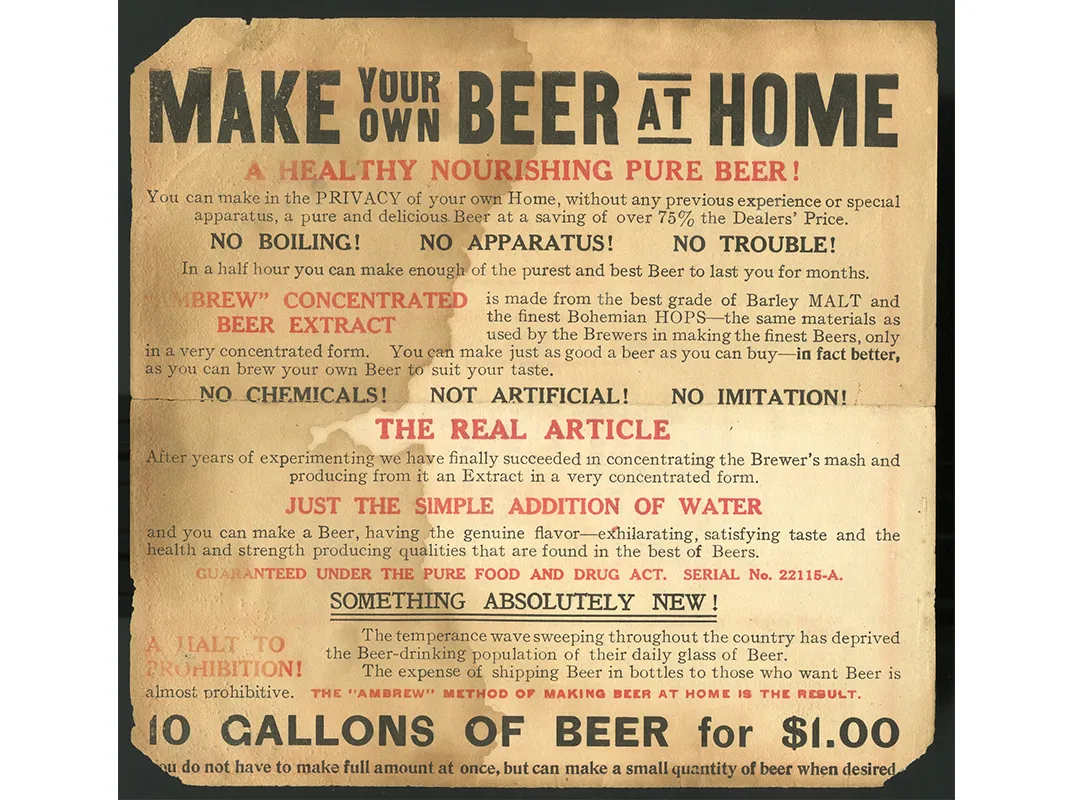

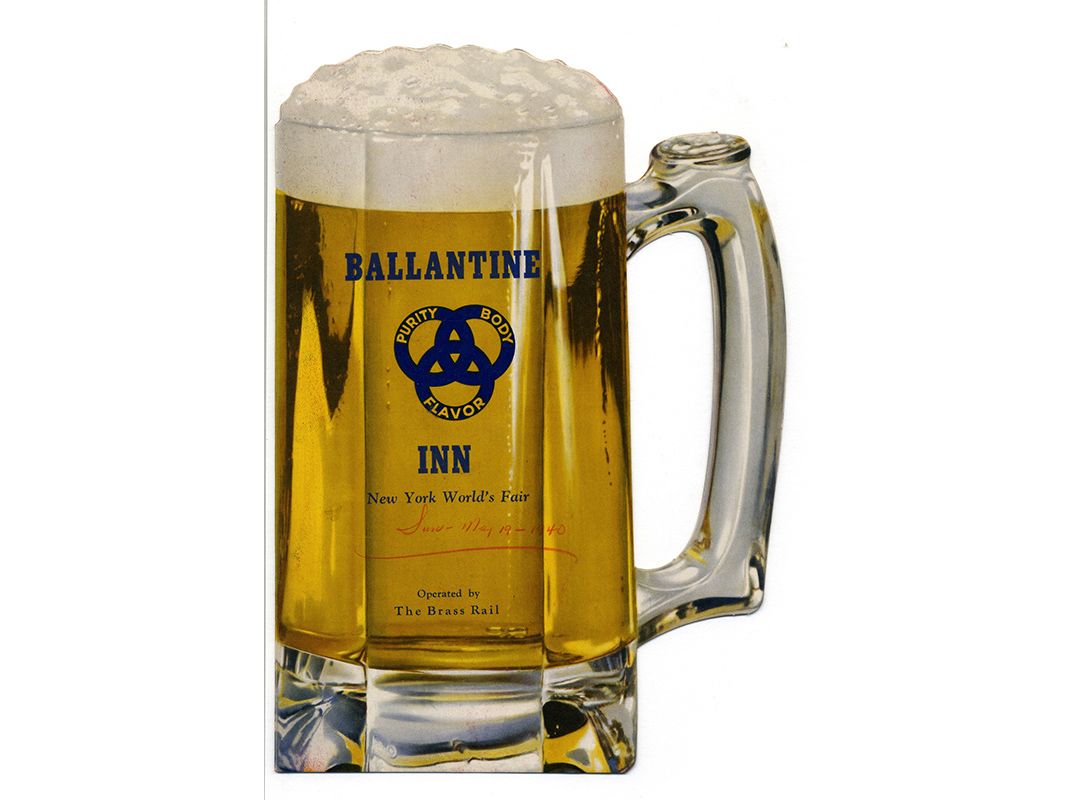

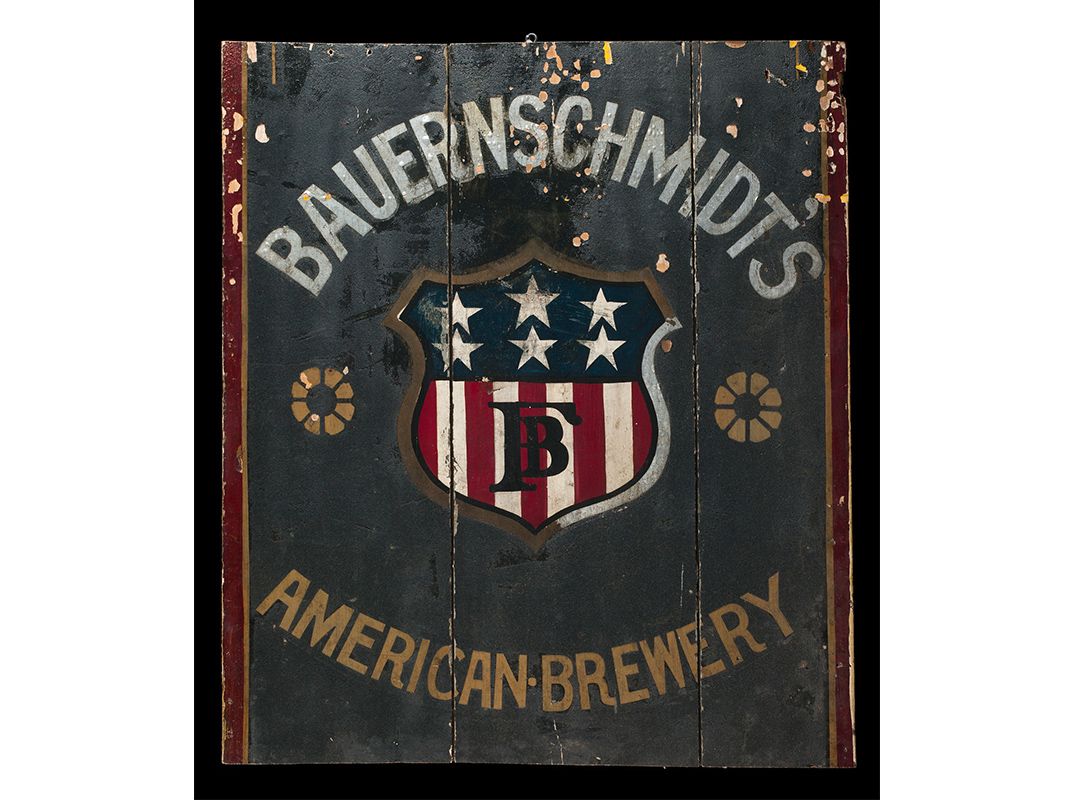

Among the artifacts she has stumbled across are examples of 19th- and 20th-century beer advertisements, sheet music and recordings of old drinking songs (a particular favorite she came across was titled “I Wish I Was Back In Milwaukee with the Pretzels and the Beer”), and a mutoscope reel, one of the first forms of film technology, showing men playing cards around a table—before their friend dumps a keg full of beer on their heads.

“For now, the museum has rich collections related to advertising history and beer making equipment, especially dating to the late 19th and early 20th century,” McCulla says. Beyond advertisements and film reels, McCulla described finding examples of brewing equipment from the 19th century—some of which was located close to where the American History Museum now stands.

“Most Washingtonians might not remember that we had the Christian Heurich Brewery, which sat on the banks of the Potomac, brewing beer where the Kennedy Center stands today,” McCulla says, referring to the renowned performing arts center located less than two miles from the museum.

The next phase of McCulla’s work will involve traveling around the country to visit brewers, hop farmers and other beer-focused professionals to collect objects and documents that could be put into the Smithsonian’s permanent collection. McCulla will also spend time interviewing those professionals, putting their words and stories together into an oral history of American brewing. And, throughout the process, her work will be shared with the public—either through events held at the Smithsonian, or through blog posts and social media.

In chronicling the history of beer and brewing in America, McCulla expects she’ll run into themes that ring true even in the 21st century—a preference for regional production and ingredients, stories of immigrants moving to American cities and bringing their craft with them, clashes—or compromises—between consumers and political figures. But in the midst of ideas that seem familiar—almost intuitive—to the 21st-century beer drinker, McCulla also hopes to illuminate a forgotten history of the people and places that helped American brewing get its start.

“One common stereotype about American beer is its identity as largely, if not exclusively, masculine,” McCulla said. “But the history shows us that the very first brewers were women and enslaved peoples who brewed beer in the home.”

She also hopes to dispel the misconception that American brewing was a typically Midwestern practice, exclusively dominated by the likes of Miller and Coors.

“When Americans think of beer today, perhaps we think of big Midwestern cities like Milwaukee or St. Louis or Cincinnati, but if we look back at the history of beer, especially in the 19th century or early 20th century, we’ll see that beer is really crucial to the urban fabric of many places, like New York City, New Orleans, and D.C,” she said. “I hope that my research will help uncover these people and places that might not be part of our current conversation.”

Of course, as the museum’s American brewing historian, McCulla’s work will involve at least some sampling of the brews she’s studying—a task she’s more than prepared to undertake. And while she’s cognizant of her role as a historian for all American beers—and is hesitant to pick a personal favorite—she’s deeply committed to the philosophy that the best beers are ones that blend both a time and a place into a complete experience. If she were to go for a beer tonight—in the middle of winter—she’d head towards the Marble Brewery in Albuquerque, New Mexico, for a pint of their imperial stout.

“If you go to their brew pub, you can sit on their outdoor patio with your beer, you can enjoy chips and salsa from a restaurant right down the street, and you can watch the sunset reflected on the Sandia Mountains in the East,” she said. “Beer, like food, like wine, is a communal thing. It brings people together, and that kind of setting, and those kinds of tastes, are perfectly represented in that kind of moment.”

The National Museum of American History will participate in the craft Brewers Conference held in Washington, D.C. April 10-13, 2017. Find Brew and Food History programs on the museum's website.

Update: 1/31/2017: McCulla clarifies her observation of the sunset. Albuquerque is famous for the reflection of the colors on the mountain range.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)