At the New “Slavery and Freedom” Show, a Mother Finds an Empowering Message for Her Young Daughters

A child’s shackles, a whip, and an auction block deliver a visceral experience of slavery

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c2/65/c2654fd1-c143-4132-9578-0b7d0a901c60/dsc06174web.jpg)

Amber Coleman-Mortley knelt on the floor with her three daughters, pointing into one of the display cases at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. They were at the beginning of the museum’s “Slavery and Freedom” exhibition, and inside the case were beads once used to count money, and a whip once used to beat slaves. One could almost hear the sound of it slashing through the air. But for Coleman-Mortley, being here was a point of pride.

“I’ve read about all this stuff, but seeing it personally is empowering, and I needed my children to understand that,” says Coleman-Mortley, who was with daughters Garvey, 8, Naima, 7, and Sofia Toussaint, 5. The Bethesda-based Digital Media Manager runs a blog entitled MomOfAllCapes.com, and named her daughters after prominent blacks in history. Garvey is named for Black Nationalist Marcus Garvey, Naima after jazz great John Coltrane's gorgeous ballad, and Sofia Toussaint for Haitian Revolution leader Toussaint Louverture. “I can trace my lineage back five or six generations, all the way back to slavery, and I’m extremely proud of that and I think they should be too—because there is nothing to be ashamed of. Nothing.”

Museum specialist Mary Elliott says that’s one of the takeaways she and curator Nancy Bercaw were hoping visitors get from this visceral exhibition. It includes many objects that exude tangible emotions, ranging from the ballast from a sunken slave ship, to shackles used for an enslaved child.

“We talk about the harsh reality of slavery, but juxtaposed against the resistance and the resilience and the survival of a people,” Elliott says. “But it is also the story of how African-Americans helped define this nation, shaped it physically, geographically, culturally, socially, politically and economically. We want people to see all that, and we want people to see the juxtaposition of profit and power against the human cost.”

Objects such as the bull whip, are as upsetting to many on the museum’s staff as they are to those visiting the long-awaited facility.

“The first time I saw that in storage, I just looked at it and had to turn away. The level of emotion on seeing that object is something I’m having a hard time explaining,” says Bercaw. “I only hope that people, when they see these objects, understand and feel some of the things that we did, because this is really documenting a past—our shared past—and it’s really the nation’s commitment to collecting, displaying and fully addressing this past. . . . I hope that people will continue to bring objects forward because it is important that we never lose sight of this history again.”

The vibe in this exhibition is different than in much of the rest of the museum. People unconsciously lower their voices as they cluster around display cases telling the narrative of how slavery began, and how nations including Britain, France, Portugal and Spain invested in the slave trade. Visitors stand for long minutes, reading the meticulously researched narratives that describe how slavery was the foundation of both the United States and of modern Europe.

Curators also hope that the exhibition teaches visitors that all Americans, both in the North and in the South, were involved in the institution of slavery. But most importantly, they want people to understand that these were human beings, with their own voices and stories, and their own challenges.

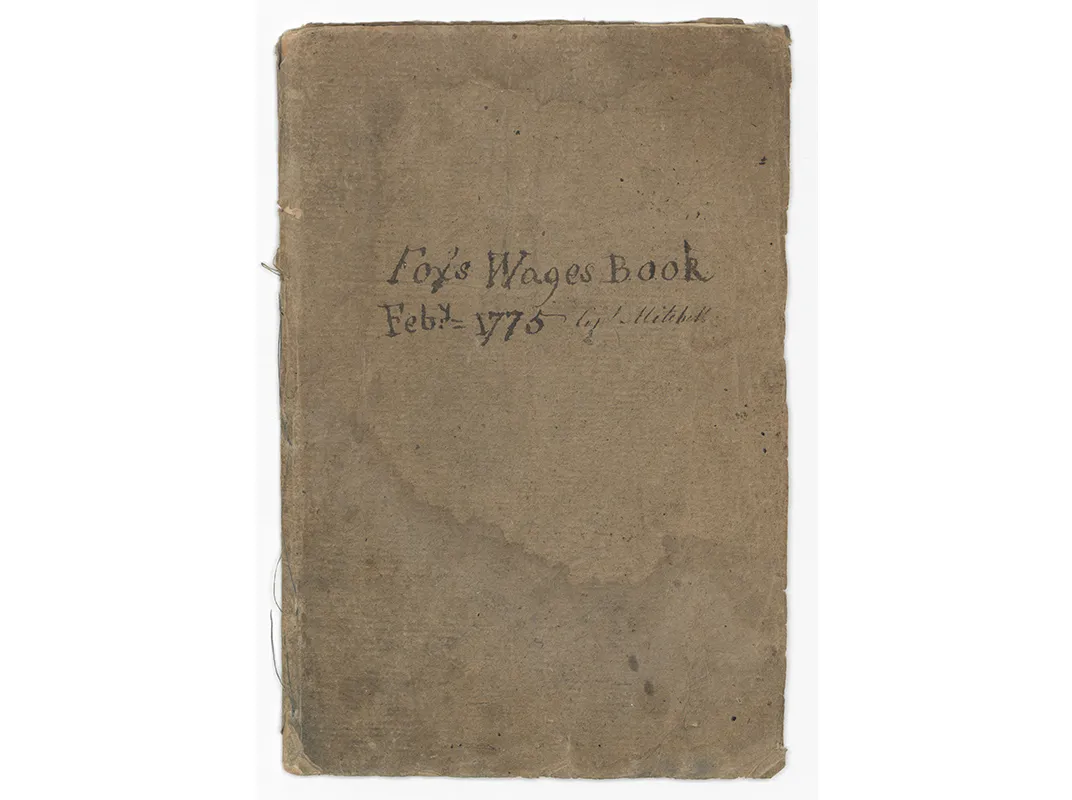

“We have a wage book from a slave ship, crew member wages, so that allows us to think more deeply about what did people wrestle with when deciding to be on board these slave ships?,” Elliot says. “Did they wrestle with, ‘I just want passage to the new world, I need to feed my family,’ or did they think ‘I’m all for this and I need to make some money?’”

As one winds their way through what almost feels like a subterranean passage at the beginning, one gets to a point where enslaved people are being transported to different parts of the nation, and into completely alien environments.

“I hope that when people walk through and experience this, they’ll see that if you were kidnapped and sold and transported with hundreds of other strangers, you would have suddenly found yourself in a very different environment. The Chesapeake, or the Carolina low country, and these all created very different African-American communities,” says Bercaw. “People say African-American as if it’s one thing. We’re looking at the roots of really different forms of expressions and we’re looking at how race was made, how our notions of black and white and difference were made in this very early era.”

She explains that the displays try to show people what it means to suddenly become black in America, to no longer be a member of an African nation such as the Dahomey kingdom.

“And then to understand the different levels of what that really meant—the political consciousness that comes out of that. The tremendous skills, the faith practices,” Bercaw explains, adding that “they were all different within these different areas.”

After the colonial era, visitors pass into a large open room. Directly in front of them, stands a statue of President Thomas Jefferson, in front of stacked bricks that represent the people enslaved by him in 1776. The exhibition explains that like many slave owners, Jefferson owned his own children and their mother, Sally Hemings. Overhead in huge letters, quotes from people and from documents such as the Declaration of Independence adorn the sweeping multi-storied walls.

In fact, the declaration is in this room, along with other freedom-related documents including the Emancipation Proclamation, the U.S. Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. There are plaques explaining how slavery fueled this nation’s economy, a cotton gin, and a slave auction block. It bears an engraving noting that General Andrew Jackson and Henry Clay spoke from the stone in Hagerstown, Maryland, in 1830. President Barack Obama alluded to the latter in his speech when he formally dedicated this museum in September.

I want you to think about this. Consider what this artifact tells us about history, about how it’s told, and about what can be cast aside. On a stone where day after day, for years, men and women were torn from their spouse or their child, shackled and bound, and bought and sold, and bid like cattle; on a stone worn down by the tragedy of over a thousand bare feet—for a long time, the only thing we considered important, the singular thing we once chose to commemorate as “history” with a plaque were the unmemorable speeches of two powerful men.

And that block I think explains why this museum is so necessary. Because that same object, reframed, put in context, tells us so much more. As Americans, we rightfully passed on the tales of the giants who built this country; who led armies into battle and waged seminal debates in the halls of Congress and the corridors of power. But too often, we ignored or forgot the stories of millions upon millions of others, who built this nation just as surely, whose humble eloquence, whose calloused hands, whose steady drive helped to create cities, erect industries, build the arsenals of democracy.

In the same room, a bible belonging to Nat Turner is on display. He led an 1831 slave uprising in which about 55 whites were killed. A hymnal and shawl belonging to abolitionist and Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman is also on display. So is a slave cabin from Edisto, Island in South Carolina.

“You can actually feel lives within that cabin,” says Bercaw, who was there when the cabin was dismantled and brought back to the museum, where it has been rebuilt. The walls visitors see that are whitewashed are original to the cabin, which was reconstructed with other boards to keep it upright.

“When we were down there collecting . . . the cabin, you could see the layers of wall paper. You could see the degree of care that people had tried to take to make their lives more livable within [it],” Bercaw says.

Some visitors find the “Slavery and Freedom” exhibition difficult to experience. But not Amber Coleman-Mortley and her daughters.

“It reinforces the strength of black people throughout the continent, throughout the globe. . . .We are the children of slaves that didn’t die so how powerful are we? How strong are we?” Coleman-Mortley asks. “We should be proud of what people had to go through so that I could get in my car, so I could drive my kids to a good school, so I could make a difference, and we should do something with that power. Go out, help the community, uplift each other.”

"Slavery and Freedom" is a new inaugural exhibition on view in the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Timed-entry passes are now available at the museum's website or by calling ETIX Customer Support Center at (866) 297-4020. Timed passes are required for entry to the museum and will continue to be required indefinitely.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)