A Member of the Little Rock Nine Discusses Her Struggle to Attend Central High

At 15, Minnijean Brown faced down the Arkansas National Guard, Now Her Story and Personal Items are Archived at the Smithsonian

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2b/31/2b313375-66fd-4422-bb17-8c19d2d3c017/et2016020381web.jpg)

Fifteen year-old Minnijean Brown thought her new high school would allow her to become the best person she could be. She envisioned making friends, going to dances and singing in the chorus.

But, her fantasy quickly evaporated. As one of the first nine African-American students to attend Little Rock Central High School in 1957, she was taunted, ridiculed and physically battered. On her first day, she faced the horror of the Arkansas National Guard blocking her entrance to the building and the terror of an angry, white mob encircling the school.

Recently, the 74-year-old activist, teacher and social worker donated more than 20 personal items to the National Museum of American History to help tell the story of the Little Rock Nine—as she and her fellow African-American students at Central High came to be known.

Nearly 60 years ago, these teenagers, none of who were particularly political, and all of whom were looking for wider opportunities, were thrust into the crucible of the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement in one of the most dangerous and dramatic school desegregation efforts in the country.

“At a certain point, I didn’t know if I would be alive to graduate from high school, or be stark, raving insane, or deeply wounded, “ says Trickey.

Several of Trickey’s school items, including a notice of suspension and the dress she designed for her high school graduation, are now on display in the “American Stories” gallery at the museum. Her graduation gown, a simple, white, swing dress with a flared skirt, and a strapless bodice under a sheer, flower-embroidered overlay, is a testament to her determination to get her high school diploma. She attended three schools in as many years, was expelled from Central High and ultimately had to leave Little Rock and her family to finish high school.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d5/d2/d5d2f6f5-4a85-44a0-b884-ffaf46686a3c/4263406548web.jpg)

Minnijean was the eldest of four children born to Willie Brown, a mason and landscaping contractor, and his wife, Imogene, a nurse’s aid, seamstress and homemaker. A native of Little Rock, she attended segregated schools and started senior high school as a 10th grader in 1956 at the newly opened Horace Mann School for African-Americans. It was across town from where she lived and offered no bus service.

In the wake of the landmark 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education that banned racial segregation in public schools, representatives from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) searched for students who would enroll in previously all-white schools throughout the south. Minnijean heard an announcement on the school intercom about enrolling at Central and decided to sign up.

Although about 80 African-American students had been approved by the Little Rock School Board to transfer to Central the following year, the number dwindled to 10 after the students were told they couldn't participate in extracurricular activities, their parents were in danger of losing their jobs, and there was a looming threat of violence. The parents of a tenth student, Jane Hill, decided not to allow their daughter to return after the mob scene on the first day.

According to Trickey, her real motivation for attending Central was that it was nine blocks from her house and she and her two best friends, Melba Pattillo and Thelma Mothershed would be able to walk there.

“The nine of us were not especially political,” she says. “We thought, we can walk to Central, it’s a huge, beautiful school, this is gonna be great,” she remembers.

“I really thought that if we went to school together, the white kids are going to be like me, curious and thoughtful, and we can just cut all this segregation stuff out,” she recalls. Unfortunately, she was wrong.

Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus called in the National Guard to keep the African-American students from entering Central. When the nine students did get into the building a few weeks later, a full-scale riot broke out and they had to escape in speeding police cars. They weren’t able to enroll until two days later when President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent in 1,200 paratroopers from the 101st Airborne Division. With bayonets fixed, the soldiers escorted the students, single file, into the school and disbursed the jeering protestors.

Although troops remained at Central High School throughout the school year, the Little Rock Nine were subjected to verbal and physical assaults on a daily basis. The African-American students were isolated and never placed in classes with each other, so they couldn’t corroborate their torment. On three separate occasions, Minnijean had cafeteria food spilled on her, but none of her white abusers ever seemed to get punished.

In December 1957, she dropped her chili-laden lunch tray on the heads of two boys in the cafeteria who were taunting and knocking into her. She was suspended for six days. That school notice is now part of the Smithsonian collection along with a heartfelt note by her parents documenting all the abuse that their daughter had endured leading up to the incident. Then in February 1958, Trickey verbally responded to some jeering girls who had hit her in the head with a purse. That retaliation caused Trickey to be expelled from Central High.

“I had a sense of failure that lasted for decades over that,” says Trickey. After she left Central, white students held printed signs that said, “One down…eight to go.”

Following her mid-year dismissal, Trickey was invited to New York City to live in the home of Drs. Kenneth and Mamie Clark, African-American psychologists who had conducted pioneering research that exposed the negative effects of segregation on African-American children. Their now famous “doll tests,” were part of the documentation used by the NAACP to argue the Brown v. Board of Education case.

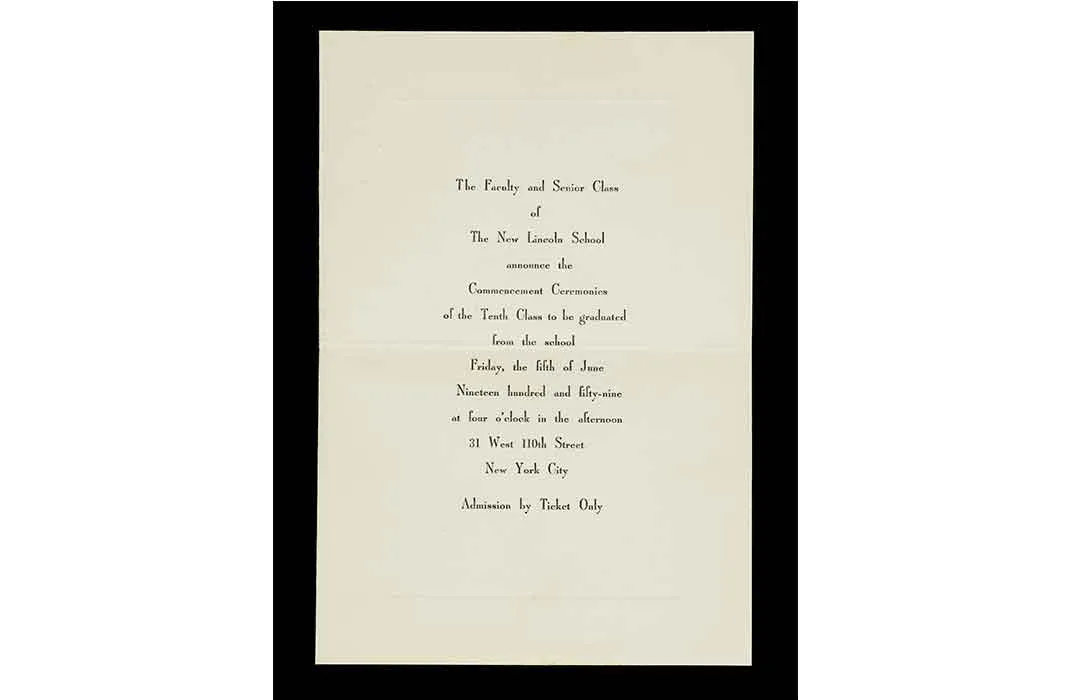

While living with the Clarks, Trickey attended the New Lincoln School, a progressive, experimental K-12 school that focused on the arts, to finish out her 11th- and 12th-grade years.

“I was very, very grateful for the gift that I’d been given,” she says. “My classmates at New Lincoln allowed me to be the girl that I should have been, and allowed me to do all the things I thought I might do at Central.”

At the end of her stay, the Clarks wanted to give her a gift and settled on a graduation dress. Trickey made some sketches and Mamie Clark took the design to her dressmaker.

“It was a perfect fit, and I felt perfectly beautiful in it,” Trickey remembers. “Many New York papers covered the graduation, and there was a photo of me with my shoulders up and I have this big smile, and I have this real feeling of relief,” she says. Along with her graduation dress, Trickey has also donated a program from this commencement ceremony.

Trickey went on to attend Southern Illinois University and majored in journalism. In 1967, she married Roy Trickey, a fisheries biologist, and they started a family, which eventually included six children. They moved to Canada to protest the Vietnam War, and she earned both a bachelors and masters degree in social work. Later in her career, she returned to the United States and served in the Clinton administration as Deputy Assistant Secretary for Workforce Diversity at the Department of the Interior. Now, she works as an activist on behalf of peacemaking, youth leadership, the environment and many other social justice issues.

According to her daughter Spirit Trickey, it took nearly 30 years before Trickey revealed to her children the full extent of her role as a foot soldier in the Civil Rights movement.

“She felt like she didn’t have the context to put it in. The nation had not acknowledged it, so it was very difficult to explain,” says Spirit, a former Park Ranger and now a museum professional. Eventually, with the airing of documentaries like PBS’s “Eyes on the Prize” in 1987, and the 1994 publication of Warriors Don’t Cry, a book by Trickey’s friend Melba Pattillo Beals, Spirit and her siblings began to understand what their mother had gone through.

Also, the Little Rock Nine started to be recognized for their contribution to desegregation. In 1996, seven of them appeared on the Oprah Winfrey Show and reconciled with some of the white students who had tormented them. A year later and 40 years after the original crisis, then-President Bill Clinton symbolically held the door open at Central High for the Nine. Clinton also awarded each of them the Congressional Gold Medal in 1999. Individual statutes of the Little Rock Nine were placed on the grounds of the Arkansas Capitol in 2005. They and their families were all invited to the first inauguration of President Barack Obama in 2008.

One of her greatest pleasures, says Trickey, came in 2014 when she was asked to speak at an award ceremony for Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani girls education advocate who survived a Taliban assassination attempt. As Trickey was being introduced at the Philadelphia Liberty Medal ceremony, the speaker compared Malala’s experiences with that of the Little Rock Nine.

“When I met that wonderful young woman, I saw myself, and it was so great to be able to make the link between her treatment and ours,” said Trickey. “I now tell youth audiences, I was a Malala.”

Trickey believes that she will be trying to come to terms with the events of her high school years for the rest of her life. “My research, my understanding continues to unfold.”

One truth that she now understands is that many of her white classmates had been taught to hate. “We couldn’t expect the white kids at Central High to go against what they had learned their whole lives,” she says.

Through the 1999 book Bitters in the Honey by Beth Roy, Trickey was able to hear the perspective of white students who resisted segregation. Roy conducted oral histories with white alumni 40 years afterwards to explore the crisis at Central High. Trickey discovered that she in particular angered white classmates because they said, “She walked the halls of Central like she belonged there.”

Trickey also realizes now that she may have been singled out for harsher treatment. At an awards ceremony in 2009, she was speaking with Jefferson Thomas, one of the Nine, when he suddenly turned to her and said, “You know, you were the target.”

“We were all targets,” she laughed at him dismissively.

“No, you were the target, and when you left, I was the target,” he revealed.

Last Spring, Trickey delivered her Little Rock Nine objects to the Smithsonian in what her daughter termed a “sacred ceremony.” John Gray, the director of the National Museum of American History, welcomed her and had a warm, gracious conversation and interview that was videotaped. Curators and star-struck interns filled the room to hear Trickey’s oral history.

She described the afternoon as a day that she will never forget because the desegregation pioneer was assured that her story and that of the Little Rock Nine would be preserved for future generations not as African-American History but as American History.

Minnijean Brown Trickey’s graduation dress, suspension notice and other items are featured in a case in the exhibition “American Stories” at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. through May 8, 2016.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Lucy_Harvey_151120_1745_WEB.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Lucy_Harvey_151120_1745_WEB.jpg)