Meet Michael Pahn: The Fiddle and The Violin are Identical Twins (that Separated at Birth)

Guest blogger and musician Michael Pahn prefers his fiddle to a violin, though they are the same instrument

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20110921031005atm-Tommy-Jarrell-Fred-Cockerham-470.jpg)

In an on-going series, ATM will bring you the occasional post from a number of Smithsonian Institution guest bloggers: the historians, researchers and scientists who curate the collections and archives at the museums and research facilities. Today, Michael Pahn, an archivist from the National Museum of the American Indian and a musician, reflects on how one instrument delivers either the raw, expressive twang of the fiddle or the pure, sustained vibrato of a violin.

I play old time country music. I find it fun, social and very democratic. I’ve played gigs with a string band before a crowd of strangers, but just as much I enjoy playing impromptu at parties with friends. People of all different skill levels come together, and the number of musicians can just grow and grow. There are hundreds, probably thousands, of tunes; and as long as someone knows the melody, eventually everyone can play along.

There is, however, one thing that can break the mood faster than a Texas quickstep—when someone shows up playing violin.

So what is the difference between the violin and the fiddle? Ken Slowik, curator of musical instruments at the National Museum of American History, puts it this way: “They are like identical twins, only one has dyed his hair green.” In other words, they are literally the same instrument, But depending on the venue, one sounds perfect and the other completely wrong.

Many would argue that it’s a matter of technique or style, but I would say the difference boils down to how emotion is conveyed. In my observations, violinists invest incredible amounts of time and effort perfecting refined expressive techniques. From the way they pull the bow across the strings to the deep vibrato on sustained notes, everything is about clarity and pureness of tone. These are precisely the same characteristics that sound so wrong in old time music. Fiddlers are expressive in a much more raw, and less refined, way. Of course, these are both equally valid and beautiful ways of playing music. But they are different and inevitably, this difference is reflected in the instruments themselves.

Two amazing instruments, both held in the collections of the National Museum of American History, illustrate this diversity. One is an ornate Stradivarius violin, one of the most beautiful, priceless instruments ever made. The other is an old, beat up fiddle that looks like it could stand a good cleaning.

The “Ole Bull” Stradivarius violin is a tour de force of craftsmanship, made by one of the most respected instrument makers in Europe. Antonio Stradivari’s instruments were highly prized from the moment they were made, and quickly found their way into the hands of royalty and the wealthy. It is not simply that Stradivari made exemplary violins—he and his predecessors created and refined the violin into the instrument we think of today. They created a small stringed instrument capable of more expression and nuance than any that had come before, and composers embraced it. Stradivari was part of an ecosystem of instrument makers, composers and musicians who, through patronage from the church and royalty, transformed music into high art during the Baroque Period.

Others have written eloquently about what makes Stradivarius instruments special. The “Ole Bull” violin is particularly extraordinary, being one of only 11 highly decorated instruments built by Stradivari that are known to still exist. It is part of the Axelrod Quartet of decorated Stradivarius instruments played by the Smithsonian Chamber Music Society, and it is called “Ole Bull” after the common practice of referring to Stradivarius instruments by the name of a significant past owner.

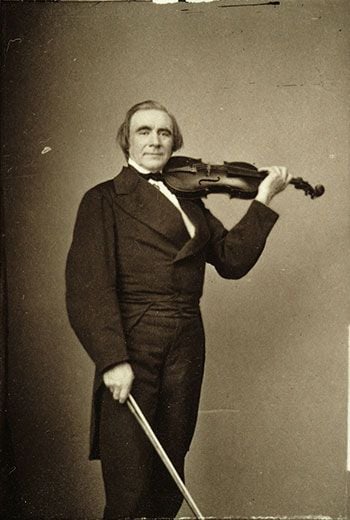

Ole Borneman Bull (1810-1880) was a Norwegian violin virtuoso who toured the United States five times in the 1840s and 1850s. Arguably Norway’s first international celebrity, Bull was one of many European musicians to tour the United States and bring classical and romantic music to American audiences. He loved America, and America loved him and he performed before sold out audiences and earned rave reviews all over the country. Bull was a fascinating character, a shameless self-promoter and patriot who advocated for Norway’s independence from Sweden and established the short-lived (and failed) Norwegian settlement of Oleana in Pennsylvania. Bull was also an avid violin collector, and in addition to the Stradivarius owned an extraordinary and ornate Gasparo da Salo violin made in 1562. Interestingly, fine violins went in and out of fashion like so many other things, and was not until Bull’s time that Stradivari’s instruments came to be more regarded than those made by other masters such as Nicolò Amati or Bartolomeo Giuseppe Guarneri.

After its development in Baroque Italy by Stradivari and others, the violin quickly spread across Europe, and became a popular folk instrument. It came to North America with European settlers, and over time a new folk music developed, based primarily on Scotch Irish melodies with a heavy dose of African American syncopation. This fiddle and string band music became the soundtrack of people’s lives in rural America, especially prior to the advent of the phonograph and broadcast radio.

Tommy Jarrell was born into a family of musicians, and had an especially deep memory for tunes. He grew up near Round Peak, North Carolina, where fiddles and banjos played every dance, every party, every cornshucking and cattle auction. Jarrell learned the way practically every other fiddler and banjo player did—by ear, at the knee of older musicians. Music accompanied every social gathering, and Jarrell played all the time.

Jarrell’s fiddle, just as an instrument, is pretty, but unremarkable. It was made by an unknown luthier in Mittenwald, Germany in the 1880s, and at the time it was imported to the United States it sold for around $6. It is a nice enough instrument, and was no doubt appealing when it was sold. Somewhere along the way, it was decorated with inexpensive inlays in the back, probably with the same spirit that motivated Stradivari to decorate the “Ole Bull” – to make something special. What makes this fiddle truly special, though, is its owner. It played hundreds of tunes thousands of times, was heard by tens of thousands of listeners, and provided a link between rural and urban audiences of American traditional music. Covered in rosin from Jarrell’s bow, it developed a patina from years of parties, dances and festivals.

After retiring from a 40-year career driving a road grader for the North Carolina Department of Transportation in the 1960s, Jarrell began playing more dances and festivals, and was able to continue the tradition of sharing old melodies and techniques with younger musicians. Many of these musicians were urban Folk Revivalists, who brought field recording equipment to Jarrell’s home, the commercial releases of which brought his music to an entirely new audience. Generous with his time, his talent and his melodies, he was among the first to be awarded a National Heritage Fellowship. Jarrell’s many connections to the Smithsonian include performances at several Festivals of American Folklife and his recordings are available on Smithsonian Folkways Records.

Of course, violinists and fiddlers make little changes to their instruments that reflect their taste and the music they play. Fiddlers often play more than one string at a time, creating droning harmonies. Tommy Jarrell sanded down the bridge of his fiddle, where the strings rest above the body of the instrument, making it easier to bow two strings at once. He put a dried rattlesnake rattle inside his fiddle, which vibrated when he played, and installed geared tuners, like those on a guitar, that made it easier for Jarrell to retune his instrument. Not even Stradivari’s instruments have remained untouched. Almost every violin he and other Baroque masters made has been modified to reflect changes in style. The most significant alterations have been to the length and angle of the neck, in part to accommodate the shift from the gut of the past to the metal strings that violinists use now.

Ole Bull was a virtuoso, and I think of his Stradivarius as a tool of incredible craftsmanship with which he created music as high art. Tommy Jarrell’s fiddle, on the other hand, makes me think of the social context in which he played music—as a joyous part of everyday life for people who often struggled. I feel so fortunate to be able to experience music from both contexts, and I appreciate how these two instruments reflect how music can mean so many different things to different people. And I can’t help but think of how each man must have identified with his instrument. I can imagine a meeting between Ole Bull and Tommy Jarrell in which they admire one another’s violins, swap, play their respective music, and maybe cringe just a little before swapping back. While each would have undoubtedly been able to play the other’s instrument, I doubt either would have felt quite right.