Lions, and Tigers and Bears: The History of the Zoo Goes Digital

Images of tea-sipping orangutans and baby chimps in strollers are part of Smithsonian Institution Libraries’ growing digital collection of zoo materials

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120705100014Jessie-and-Josephine_Thumbnail.jpg)

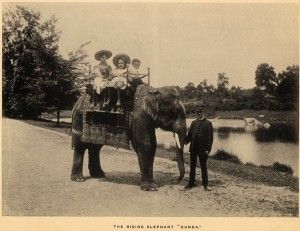

In A Winter’s Tale, Shakespeare wrote one of the strangest stage directions ever given in the history of theater: “exit, pursued by bear.” This order is difficult to follow in modern-day productions of the comedy, but in the 17th century, bears and other animals we now call exotic were, for better or worse, often assimilated into daily life. Many of the images in Zoos: A Historical Perspective, a collection of pamphlets, photos, maps and guidebooks beautifully displayed by the Smithsonian Libraries, reflect a similar sentiment. Bears can be seen climbing poles, elephants in Australia carry elegantly clad school children, and tigers stare lazily at humans inches away from their cages.

The collection features pamphlets, sketches and photos from not only the Smithsonian’s National Zoo, but from zoos across 30 states and 40 countries, making it the largest project of its kind, and providing a valuable perspective on the changing relationship between animals and humans throughout history. The photographs demonstrate, for example, how zoos were once places frequented for the sake of spectacle, and the evolution of the zoo into what it is today: an educational and conservation-minded institution.

Head of Information Services Alvin Hutchinson hopes that the online collection will give visitors “an appreciation of the history of zoos and the fact that they’ve been around for more than 300 years. They were once a place for oddballs and curiosities, but they’ve evolved into much more than that.”

The current collection is just one example of a larger effort by the Institution to digitize a host of print documents. “This collection was sitting in boxes and folders,” says Hutchinson, “and we put out a call for things not easily findable, and discovered these pamphlets.”

Hutchinson hopes to digitize the entire collection one day (the current exhibit features about 80 images), based on the feedback he’s received from those already on display. “I’ve gotten many calls,” he explains. “Mostly out of curiosity, but some have been very personal. One guy called and told me that his relative in England had done the stonework photographed in one of the zoos. The feedback has been great.”

Some of the images—lions sitting behind heavy metal bars, monkeys in cages too small—may seem a bit disturbing, but they serve as a reminder of how our understanding of animals and animal intelligence has changed over the years. Whereas once we poked fun at how easily chimps could look like humans (a photograph in the collection shows a family of chimps sitting down to dinner, complete with china tea cups and a tablecloth), we now view these similarities in the context of scientific understanding.

At once contemplative and whimsical, the collection is a valuable lesson in how far we’ve come and how far we have yet to go.

View it here, along with an introduction from the curator.