If You Can Make It Here: The Rise of New York City

Saul Lilienstein discusses how the city rose from the 1929 crash and became stronger than ever, Saturday at the Ripley Center

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20121130115030NYC-Thumb.jpg)

Saul Lilienstein was just your average kid growing up in the Bronx. He rode the train to the dazzling Times Square and music classes in Manhattan and watched Joe DiMaggio from his rooftop overlooking Yankee Stadium. If this sounds like the same sort of nostalgic yarn Woody Allen spins in Annie Hall when his character Alvy tells the audience that he grew up underneath the rollercoaster at Coney Island, Lilienstein is here to tell you it’s all true.

“He might have been born in Brooklyn but you’d be surprised how close the character was of kids from either Brooklyn or the Bronx and their utter attachment both to their boroughs and to New York as the center of their world.”

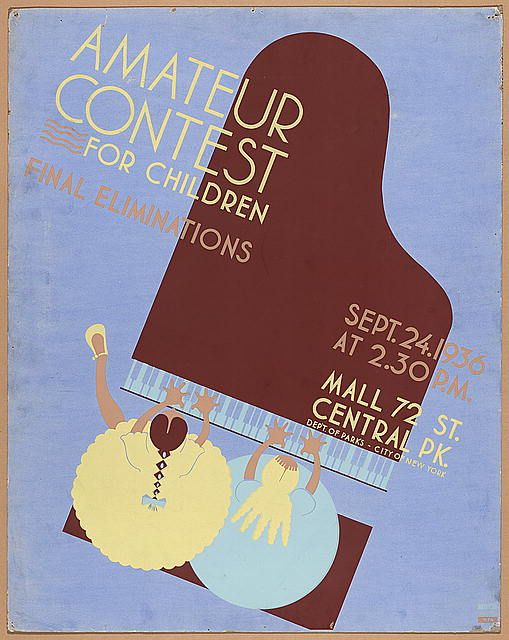

While it may not be surprising today that New Yorkers don’t suffer any insecurities about their town, the city’s fate as a global capital seemed uncertain after the stock market crash of 1929. That’s where Saul Lilienstein, a music historian, plans to pick up when he presents “New York in the Thirties: From Hard-Times Town to the World of Tomorrow” with colleague George Scheper for Smithsonian Associates. His Saturday seminar will touch on everything from Broadway to Harlem, Mayor LaGuardia to city planner Robert Moses, and explore how the city rose from the crash.

“I’ll always be a New Yorker, there’s no question about it. That’s my neighborhood,” says Lilienstein. Born in 1932 in the Bronx, Lilienstein takes what has become a familiar story of a city’s triumph–demographics, government support, new art forms and platforms–and tells it from a unique point of view, reveling in the seemingly endless potential available to any kid with a nickel.

The familiar players will all be in attendance Saturday: the New Deal, Works Progress Administration, Tin Pan Alley, Radio City Music Hall, the Cotton Club. But Lilienstein weaves personal memories into the narrative to bring New York in the 30s and 40s to life.

Like when he won an award in 1943 for selling more war bonds than any other Boy Scout in the Bronx. “I was chosen to lay the wreath at the opening of the Lou Gehrig memorial outside of Yankee Stadium,” remembers Lilienstein. “And the New York Daily News had a picture of me and it said, boy scout Saul Lilienstein lays the wreath at the Lou Gehrig memorial and then it mentioned the people standing around me: Mrs. Babe Ruth, Mrs. Lou Gehrig.” For a boy whose life revolved around riding the subway to any and every baseball game he could, the memory stands out as a favorite. “And then we all went out to lunch together to the Concourse Plaza Hotel.”

Now an opera expert, Lilienstein has a musical background that stretches back to his high school days. “I went to a high school that had six full symphony orchestras in it. I’m not exaggerating,” he says. Manhattan’s High School of Music & Art is a public school, but was the project of Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, who founded the school in 1936 as part of a trend of government support for artists and the arts. Factors like these seem almost impossible to imagine today, says Lilienstein, when rhetoric often villainizes anyone who benefits from the government. “But, it was a marvelous thing that generated theater and music in the city.”

He remembers taking the subway to music lessons in Manhattan where he trained with the first trombone from the New York Philharmonic, for free. Density created audiences large enough to support world renowned cultural institutions. A public transportation system open to anyone helped democratize access to those institutions. And Lilienstein’s story is just one of many from a city built to embrace the arts.

Times Square, for example, served as a sort of theater lobby for the entire city, according to Lilienstein. “It’s this place where a huge, milling crowd of people are getting something to eat and talking about what they’ve seen,” he says. “It’s not just a place where people are passing through.”

Lilienstein even goes so far as to defend the billboard funhouse that is Times Square today, saying, “Well it’s not quite the same. There are some differences: you can sit down in the middle of it now. I’m not one of those people who thinks everything gets worse, a lot of things get better.” But, Lilienstein pauses for a bit before adding, “Nothing gets better than New York in the 30s and the early 40s!”

“New York in the Thirties: From Hard Times Town to the World of Tomorrow” takes place December 1, 9:30 a.m. to 4:15 p.m. at the Ripley Center. Purchase tickets here.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)