How the Heroes of Africa Triumphed Against All Odds

At the African Art Museum the inspiring stories of 50 individuals from the continent are honored in classical and contemporary works of art

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/58/74587b41-9722-428c-8785-612260480412/2018-11-1_d20190007_brad.jpg)

He stands more than seven feet tall, with piercing eyes that seem almost alive, staring through the souls of entranced visitors into the future. The statue, Toussant Louverture et la vielle esclave (Toussant Louverture and the Elderly Slave), commands the room, sending out a powerful vibe that is tangible and tactile.

“This is one of the masterpieces of our contemporary collection,” explains curator Kevin Dumouchelle. “I sort of frame it as our own Statue of Liberty here in the middle of the exhibition.”

Dumouchelle built the exhibition, “Heroes: Principles of African Greatness,” now on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art, around this powerful piece. The show features nearly 50 works by classical and contemporary artists from 15 African countries that weave a tale of heroic principles and people in Africa’s history. Visitors are meant to consider core values ranging from justice and pride to honor and piety. Each work is paired with an African historical hero—or heroine—whose lives embody battles for freedom and leadership. Every piece is given a label, such as honor, independent, or woke, to illustrate the values these leaders showed in their lives and accomplishments. The statue of Toussaint Louverture, by the late Senegalese sculptor Ousmane Sow, is Liberty.

“Sow developed this very idiosyncratic, personal sort of sculptural style, building heroic, monumental, larger than life figures . . . out of a sort of iron sculpture covered in fiberglass and cotton that is fundamentally built by wrapping pieces of textile in earth and adhesives and pigments and a variety of other stuff,” Dumouchelle says. “Louverture was the leader who helped crystalize what became the Haitian Revolution, throwing off the French rule of the island then known as Saint-Domingue.”

For museum director Gus Casely-Hayford, one of the most compelling pieces in the show is a work by the legendary coffin sculptor Paa Joe of Ghana called Fort William-Anomabu.

“It is affecting in a variety of ways because it is a coffin, but it is also a depiction of one of the slave castles as well,” explains Casely-Hayford, who is focused on the message the heroes and artists deliver to visitors to the exhibition.

The fort, in Ghana, was among several European structures built on what was then known as the Gold Coast. But it was also one of the only ones to have a prison purposely built inside to hold enslaved people awaiting transport to the Americas. It was the center of the British slave market until 1807. Paa Joe’s piece, labeled as Witness in this exhibition, greets visitors as they enter, and Casely-Hayford calls it one of his most poignant works.

“This is a coffin, but you think of its connections to lost histories as well as lost lives, but then, if you can, imagine this being about one particular person as well and one family as well as their loss,” the museum director says. “I just think the ways in which those sorts of layers of interpretation of loss stories is something that we can all relate to. This institution was created to try to address some of that—that we come from a place of sharing that loss as peoples of African descent. But there are places like this in which we are actually trying to find ways of navigating our way back.”

Curator Dumouchelle explains that the museum is tying the idea of the coffin as a witness and memorial to the lost history of the enslaved Africans imprisoned in the fort. The hero connected with it, is writer, composer and abolitionist Ignatius Sancho. He wrote a number of powerful letters that became one of the earliest records in the English language of the horrors of the slave trade.

“Sancho was born on a slave ship off the cost of the Caribbean and through a number of remarkable events, found his way to Britain as a young man,” Dumouchelle says. “He found his way to freedom, and eventually opened his own shop in Westminster and became famously the first person of color to vote for Parliament in the early 18th century.”

An incredibly graceful statue, called Africa Dances depicts a woman caught in the midst of a powerful performance. Labeled Dignity, the piece by Nigerian artist Benedict Enwonwu is part of a series begun in 1949. The light flows like water off the cold-cast resin, predecessor to a 1982 bronze casting. It is believed to have been painted by the artist to see just how that would look.

“Enwonwu was a major pioneer in the development of modernism in 20th century Nigeria. . . . He looked to this idea of a beautiful young woman standing and rising on her own two feet and celebrating herself, celebrating her own dignity in life as an emblem in a way of the mid-century moment in Africa,” Dumouchelle says.

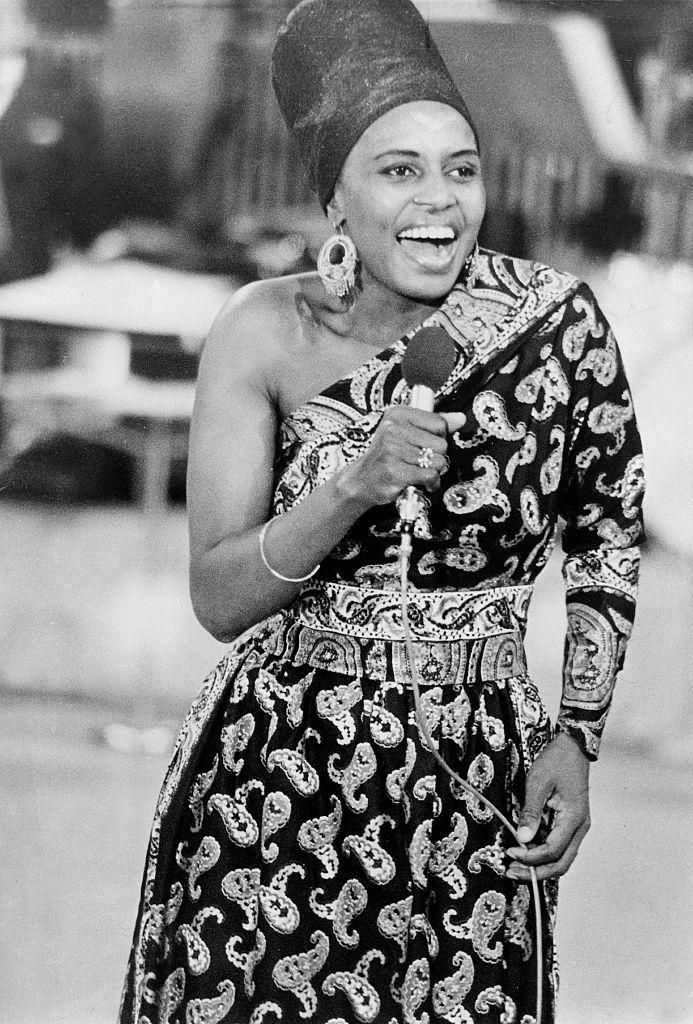

In this case, the museum connected the idea of dignity to South African singer Miriam Makeba, who became a global superstar and inspired activists around the world.

“In the mid-20th century, she became an icon, known as Mama Afrika, of Africa rising, of African independence movements,” Dumouchelle explains. “She actually sang at the independence celebrations of a number of difference sub-Saharan African countries in the 1960s and 70s, and moved throughout these countries in the 60s, 70s and 80s when she was banned from her native South Africa by the apartheid government of that time.”

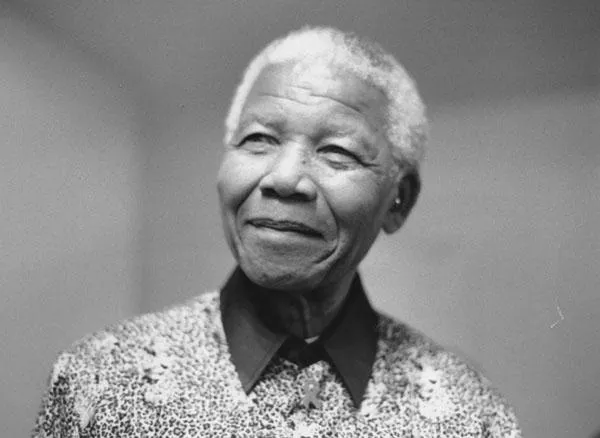

There are a number of striking works on display in this exhibition, including a painting by Nelson Mandela, labeled Revolutionary and created by the former South African President on a return to Robben Island where he was once imprisoned. Under the label Pride, is a mixed media painting called AMA #WCW. The gender nonconforming South African artist Dada Khanyisa created a portrait of six young woman enjoying cocktails, complete with hair extensions and jewelry on the surface, with smartphones embedded in the work.

But one of the most interesting things about Heroes is its attempt to focus on both the past and look towards the future, partly through a Smithsonian-developed, web-based Hi app. First developed for the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, the app doesn’t require downloading, and offers visitors an added layer of digital content including images and key facts connecting the artwork to their corresponding “heroes in history.” Museum director Casely-Hayford recorded some 40 videos for the app. There’s a music playlist as well on Spotify.

“I am so thrilled that we have these technologies. It will mean that we can create a whole new layer of interpretation on these really powerful objects,” says Casely-Hayford, who adds that not only can people come into the museum and read the traditional written interpretation, now they can go deeper in a way he thinks will thrill and engage younger people. “You can of course read the labels, but then you can choose to engage through these digital interfaces in new layers of reconsidering these works and giving them a wider, broader, deeper and I think more emotionally complex set of channels.”

Casely-Hayford says this exhibition gives people a chance to get close to histories that have been obscured for all sorts of terrible reasons. He thinks the National Museum of African Art is here for both the celebration of great art, but also for the celebration of those African stories that have been neglected for far too long.

“These stories are against all odds,” Casely-Hayford says. “They’re about people who manage to somehow triumph against what seems like an impossible situation. They’ve done incredible things, and they are things that have changed the way in which we see Africa.”

Currently, to support the effort to contain the spread of COVID-19, all Smithsonian museums in Washington, D.C. and in New York City, as well as the National Zoo, are temporarily closed. Check listings for updates. “Heroes: Principles of African Greatness” was scheduled to remain on view indefinitely at the Smithsonian's National Museum of African Art.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)