Hirshhorn Curator Explains the Significance of the Huge Marcel Duchamp Donation

Washington D.C. art lovers Aaron and Barbara Levine promise 50 important works to the museum

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/6b/f26b209b-5739-4809-8568-ff18bc18c74b/3964016.jpg)

Up to now, the single piece of work from Marcel Duchamp in the Smithsonian’s contemporary and modern art Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden was a late Objet-Dard, a bronze four-inch piece that looked like a coathook or door handle. Soon, the museum will be home to one of the world’s strongest collections of the influential French Dadaist. To mark the impending 50th anniversary of the death of the French artist October 2, Washington, D.C., collectors Barbara and Aaron Levine recently announced a promised gift of 50 artifacts and a library of more than 150 volumes, along with other archival ephemera.

It’s the single most significant gift to the museum since the two gifts made by the museum's founder Joseph H. Hirshhorn and establishes the Hirshhorn as among the nation's best Duchamp resources, alongside the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Works from the promised gift will go on display in October 2019 for one year, says senior curator Evelyn Hankins, accompanied by a major publication.

And it’s an important gift as well, in the fact, that it is Duchamp, of whom Hirshhorn Director Melissa Chiu says, “reshaped the definition of what we might consider to be art today, setting the stage for all that followed.”

“Honestly, to my knowledge, I think it’s one of the most important private collections in Duchamp that’s out there,” Chiu says. “It’s one of the most important examples of Duchamp in private hands. So for us to get a collection like that is really remarkable.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cc/b5/ccb57843-edaa-4a95-8727-f032f30ab41a/aaa_miscphot_5656.jpg)

“The core of the collection is approximately 35 works by Duchamp which span, really, the full range of his career,” Hankins says. “I can’t even express how it’s going to transform our holdings.”

Because Duchamp was so important in the development of 20th-century art, she says, “to have this now as the core of our holdings will really ground much of the work that we’ve been collecting over the last several decades.”

Duchamp, she adds, “redefined what an artwork could be and he did it in many different ways. But I think the core of his significance is the way he challenged the role of the artist, the way an artist’s authenticity may be conveyed in an artwork; this idea that the artist didn’t actually have to make the artwork, but instead it was the idea that mattered, over the idea of craft.”

Born in 1887, Duchamp took the world by storm with his Cubist painting, Nude Descending a Staircase, at the 1913 Armory Show in New York City. But after a couple of other notable Cubist works, he left behind what he called “retinal art” for a more cerebral approach, opening the door for conceptual art.

Influenced by the Dadists, Duchamp coined the term “readymades” for found objects to which he often did nothing, except to sign his name—or pseudonym, “R. Mutt.” He applied this technique to a urinal titled Fountain that he submitted to a non-juried art show in 1917 that was nonetheless rejected.

The Levines’ gift to the Hirshhorn includes a 1964 edition of a readymade, a wooden Hat Rack, conceived in 1917, whose six arms resemble a scurrying spider when it is displayed suspended from the ceiling, robbed of its usefulness. Another, the 1916 With Hidden Noise (in a 1964 edition) is a ball of twine held between two brass plates—inside the twine is an unknown object, placed there by avant-garde collector Walter Arensberg. Comb is just that; conceived in 1916 and reproduced in 1964, it is a metal comb with an enigmatic message printed on the side in a wooden case.

Even lowly sink stoppers get renderings in bronze and silver and are displayed as if they were prized medallions. Some of the readymades in the collection are alterations of existing items. One is Apolinère Enameled, an advertisement with added paint. The 1921 Why Not Sneeze, Rose Sélavy? is a birdcage that appears to be full of objects including sugar cubes, that are actually marble. It uses another one of the artist's pseudonyms, Rose Sélavy, a variant of the French, “Eros, c’est la vie,” or “Eros, such is life.”

More bold was a “rectified readymade,” defacing perhaps the most famous image of art, a 9-by-11-inch reproduction of Leonardo DiVinci’s Mona Lisa with a mustache and goatee, now titled L.H.O.O.Q. (another randy pun that, when the letters are pronounced in French, Elle a chaud au cul, approximate a crude phrase).

There is also a second Mona Lisa image in the collection, this one from a playing card, that comes minus the goatee, titled Shaved L.H.O.O.Q. “People have called his sense of humor impish,” Hankins says of Duchamp. And the Levines, and Aaron Levine in particular “might have a similar sense of impish humor, honestly. He’s very smart, very thoughtful and has this great sense of humor.” (The Washington Post once reported that toilets in the Levine home are playfully stenciled with the same pseudonym, “R. Mutt,” that Duchamp used to sign his urinal, Fountain.)

The earliest work in the collection is an elegant 1909 pen and ink drawing of Duchamp’s sister Yvonne. There are notes more than a century old for proposed sculptures. Augmenting works by the artist’s contemporaries include photographs of Duchamp by artists from Man Ray, Tristan Tzara and Henri Cartier-Bresson to Diane Arbus and Irving Penn. “There’s also a fabulous photograph by Man Ray called Dust Breeding Dust [Over Work by Marcel Duchamp], which is indicative of the close relationship between Duchamp and Man Ray.” It was taken in 1920, when Duchamp was spending years making The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, also known as The Large Glass.

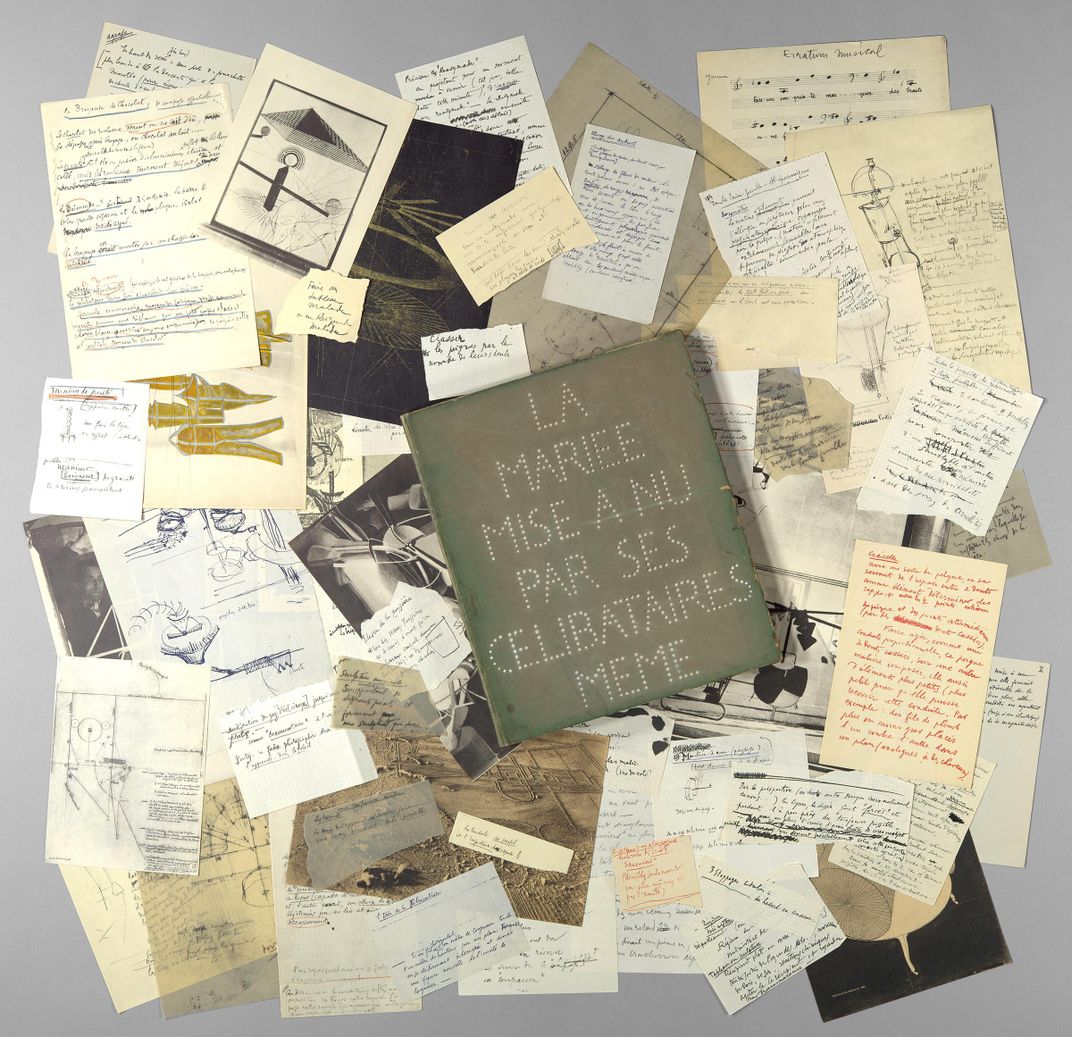

Duchamp left it under his bed for a time, Hankins says, “and Man Ray took a photograph of the dust collected on The Large Glass. And then Duchamp affixed that dust permanently to The Large Glass.” For all of his work on The Large Glass, which is in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Duchamp amassed a box of very exacting replicas of manuscript notes, drawings and photographs of it that he produced in an edition of 300 in 1934 in a piece he called The Green Box, which will be coming to the Hirshhorn. It accompanies another box of 68 miniature replicas of works by Duchamp he produced called The Box in a Valise.

Each of the boxes displays “an obsessive attention to detail” that belied his fame as someone who eschewed craft in favor of ideas, Hankins says. “There’s this wonderful irony in these compendiums that he made that he was obsessive about the details, and the craft.” The Levines collected their Duchamps over a two-decade period, augmenting the other pieces of modern art hung at their D.C. home.

“Their other collecting interests focus on conceptual art,” Hankins says, “so the idea of grounding the collection in Duchamp gave their own collection a kind of historical foundation.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6c/4c/6c4c6d16-7c72-4489-bfb5-dcf490bb7668/levines_.jpg)

Though he seemed to give up art for many years to become a competitive chess player, Duchamp lived long enough to see his influence spread to artists later in the 20th century from Robert Rauschenberg to Andy Warhol, who once shot one of his 1966 screen tests of Duchamp and which Hankins hopes to include in the exhibition next year.

The Levines have a long association with the Hirshhorn; Barbara Levine served on the Board of Trustees from 2000 to 2012. “This donation of art gives the public access to our collection of Duchamp works that we have lived with and loved. A free museum with nearly one million visitors a year is the perfect home for these art works,” the Levines said in a statement.

“Their realizing that the Hirshhorn was their hometown museum and the impact it could have on our collection, as well as the broader impact you can have, because of the Hirshhorn’s unique position on the National Mall” had an effect, Hankins says. “We have a very different kind of visitor audience than many museums—we’re free, we’re part of the Smithsonian. And I think that they realized that not only would it transform our collection but it would have a broader [national] impact by the number visitors and the types of visitors we have.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)