High-Tech Tracking Reveals ‘Whole New Secret World of Birds’

A study of Kirtland’s warblers found that some continue exploring long distances even after they reach their breeding grounds

:focal(926x160:927x161)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d7/07/d707e9ed-1ed0-40d5-8675-6cbb1df90895/2020_kirtlandswarbler_timromano-7149.jpg)

For Kirtland’s warblers, migration isn’t as simple as getting from point A to point B. The small songbirds, easily recognizable for the contrast between their yellow bellies and the dark-streaked feathers above, have long been known to spend the winter in the Bahamas before striking west for their breeding grounds in the pine forests of Michigan.

What ornithologists didn’t know was that many of these birds keep making long trips even when they arrive at their breeding grounds.

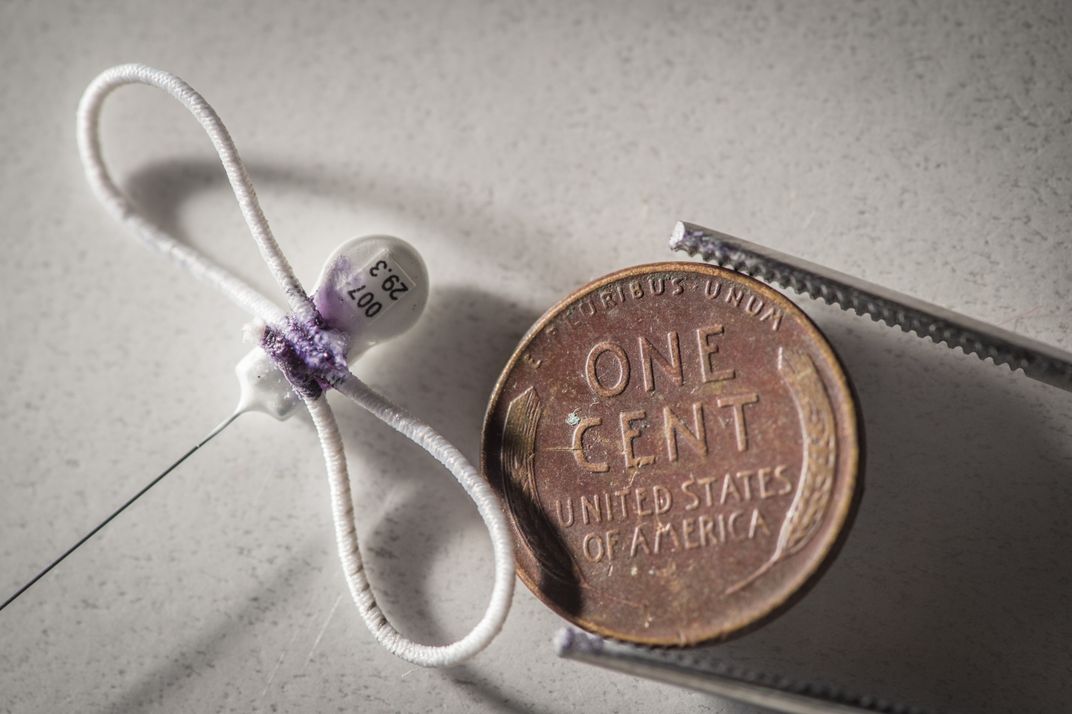

“We really had no idea Kirtland’s warblers were doing this,” says Nathan Cooper of the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center. The new study, published in Current Biology, was designed to detect how conditions where the birds spend their winters affect the birds’ chances for survival and reproducing during migration and the breeding season in mid-May. To find out, Cooper fitted more than 100 warblers with tiny radio tags weighing only about a third of a gram, which is less than the weight of a raisin. Signals from the tags are picked up by a network of telemetry receivers called the Motus Wildlife Tracking System. The network is the closest biologists can get to actually following along with the birds as they flit along their migration route.

What Cooper and co-author Peter Marra found, though, wasn’t as simple as one big round trip. Once the birds arrived in Michigan, many of them started making long trips to different spots within the breeding area. The trips ranged anywhere from three to 48 miles, and most of the traveling birds were those that weren’t breeding that season. What could they be up to?

Ornithologists have a word for the birds that bop around a bit during breeding season. These birds are called “floaters,” and experts knew that these birds moved around the space of particular breeding sites. But the behavior of these birds isn’t easy to track.

“Typically, floaters are difficult to catch because you can’t tell a floater from a breeder just by looking at them,” Cooper says.

Only the radio telemetry data could bring the long-distance movements of the floaters into focus. The question was why the floaters were making such long trips. The answer might have more to do with the next year’s breeding season than the current one.

“In theory, birds can collect three types of information about where to breed: personal, social, and public,” Cooper says.

A warbler will fly around to look at a spot to see if it’s a suitable habitat—if enough food, cover and other birds are available, for example. The birds can also pick up on what other birds are doing, or social information, such as where other warblers are breeding. And public information, to a warbler, includes things like how many hatchlings other birds raised during the season.

The warblers are picking up on all these cues, but, in the case of the floaters, it seems that breeding success made the most difference. The warblers moved around most when babies were in the nest and were starting to fledge.

“We think the birds were flying around looking and listening for nestlings and fledglings, noting areas where they heard a lot of them and thinking ‘This is a good place to breed next year because others were successful here,’” Cooper says.

But it wasn’t just floaters that were moving. “I am really surprised to learn how far breeding birds move during the breeding season,” says Weber State University ornithologist Rebecka Brasso, who was not involved in this study.

The floaters are somewhat expected, especially without nests to tend. But some breeding birds—about 11 percent of the study sample—moved significant distances as well. Those birds traveled to spots between six and 28 miles away, which means scientists may need to expand the breeding range included in their studies.

“I think most of us studying breeding songbirds assume that breeders remain within 600 to 1,600 feet of their nests during the nesting period,” Brasso says. “In fact, a lot of us plan our field studies and interpret our data based on these assumptions!”

How Kirtland’s warblers plan for the future by exploring will affect how conservationists protect them. “If many birds are moving around at larger scales than we realize, then we may not be protecting the right areas,” Cooper says.

If we want to protect Kirtland’s warbler—and other species that move in similar ways—then conserving the overwintering and main breeding spots wouldn’t be enough. The birds require some flexibility to account for all the sightseeing they do in planning for the next breeding season. Birds don’t need just one place to live, but many.

“A significant implication of this is that we, both the scientists and the public, need to expand our image of the 3-D space a bird needs during a breeding season,” Brasso says. That goes for backyard birders, too. “If I put up a nest box in my backyard for a chickadee and fill my yard with native plants to ensure food availability near the nest, how sufficient is this? Do I need my whole neighborhood to do the same? Two cul-de-sacs over, should they do it because my chickadees are taking day trips farther from the nest?” Brasso asks.

And the warblers probably aren’t alone. Whether zoologists are studying birds or other creatures, tracking animals through space and over time is difficult, and it’s often difficult to pick out which animals in a population are the floaters and which are the ones more likely to breed. The emerging picture will undoubtedly alter what ornithologists have expected.

Or, as Brasso says, “I think that this new technology is going to open up a whole new secret world of birds.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)