Chronicling Hip-Hop’s 45-Year Ascendance as a Musical, Cultural and Social Phenom

The groundbreaking box set “Smithsonian Anthology of Hip-Hop and Rap” features 129 tracks, liner notes and an illustrated 300-page compendium

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f9/52/f95203e7-4b54-43a8-ab0f-e2620abbef50/hha-product-shot-w-logos.jpg)

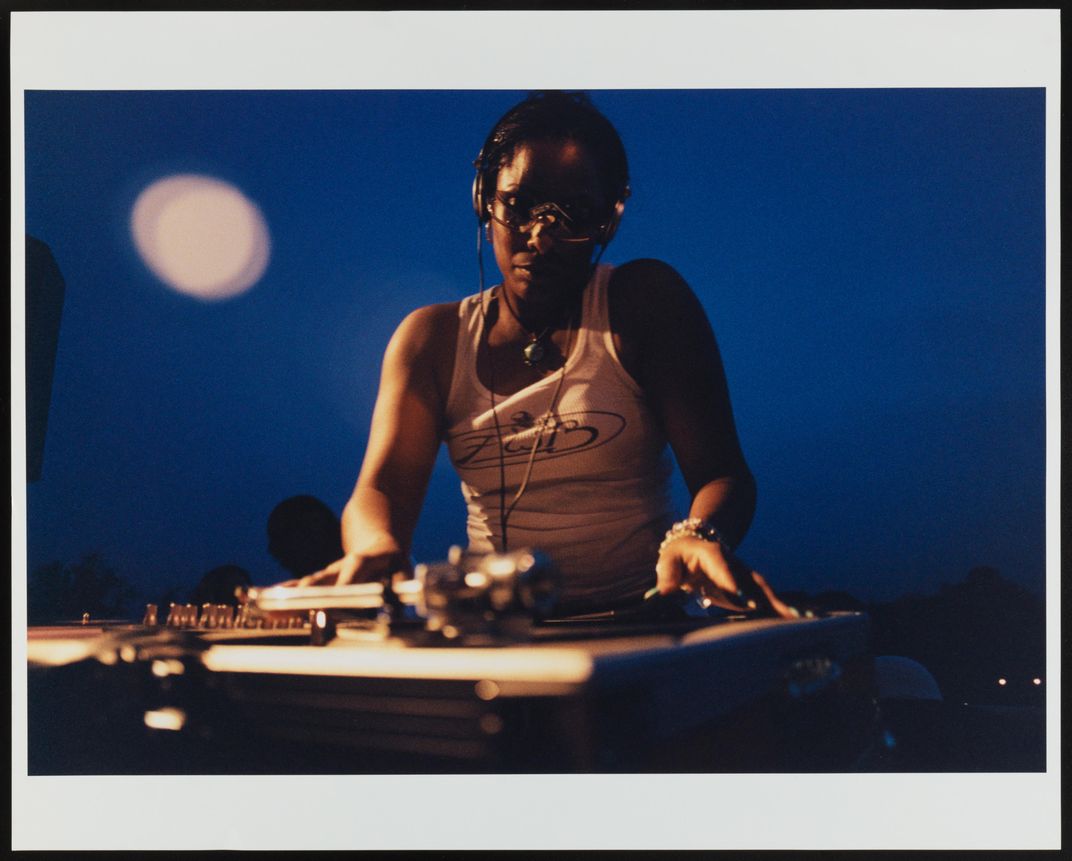

In the 1970s, New York City was reeling from an economic collapse ushered in by the decline of the manufacturing industry, white flight and the construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway. To cope with the financial and social hardships of the era, many people turned to art, and the Bronx became a hotbed for creativity. By the latter half of the decade, graffiti covered subway cars, and abandoned buildings provided the perfect backdrop for block parties set to the soundtrack of a new sound: hip-hop.

In 1977, DJ Afrika Bambaataa began hosting his own hip-hop events in the borough. Today, having such festivities might seem insignificant, like a fun way to relieve tension after a day at work or a way to meet new people. But at the time when Bambaataa began throwing these fetes, he felt that they served a larger cause and that hip-hop played a fundamental role in New York’s Black community.

After an influential trip to Africa, Bambaataa realized that he could use hip-hop to help poor youths, and he also founded a street organization called Universal Zulu Nation to help his mission, wrote hip-hop historian Jeff Chang for Foreign Policy in 2009. Before long, local critics were writing that Bambaataa was "stopping bullets with two turntables."

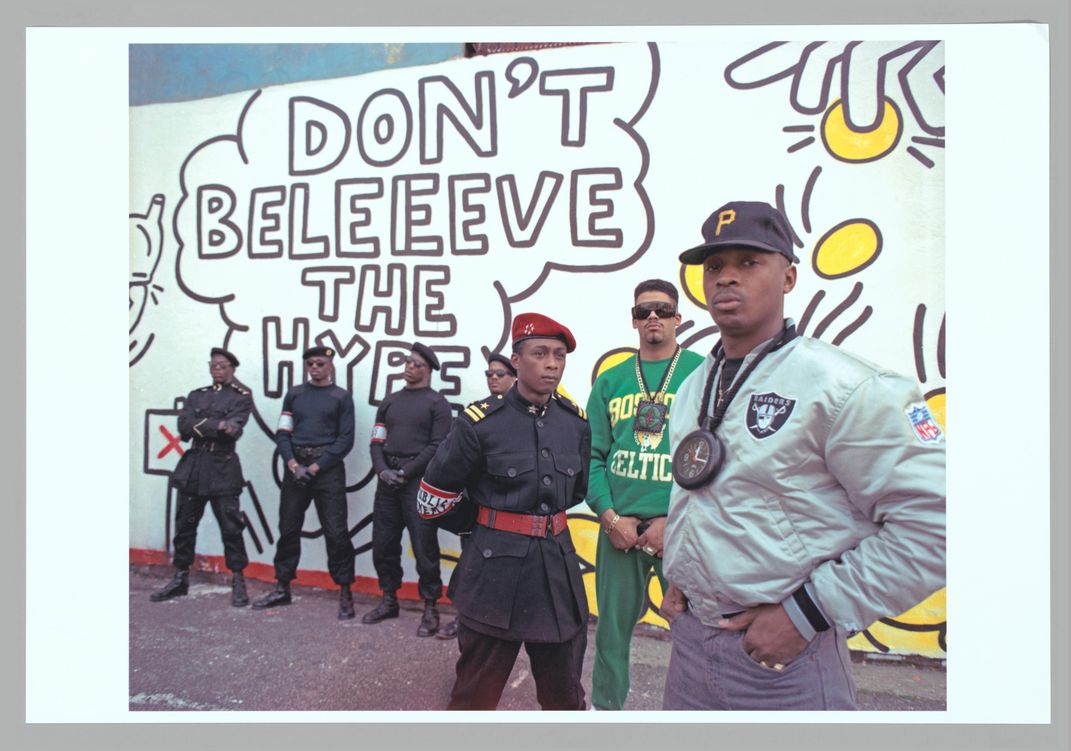

“DJ Afrika Bambaataa used the concepts of peace, unity, love and fun to lessen the realities of systemic hate and institutional racism [people] faced in everyday life,” writes Public Enemy front man Chuck D in the newly released Smithsonian Anthology of Hip-Hop and Rap.

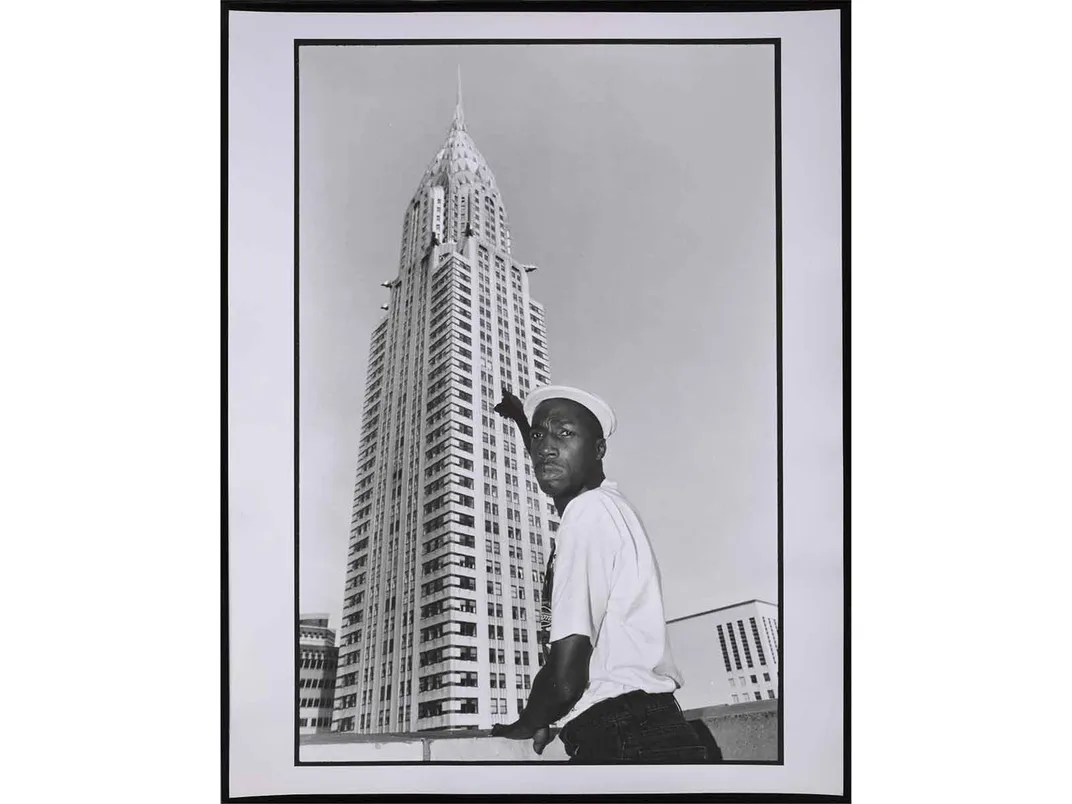

Chuck D’s essay on Bambaataa—as well as Bambaataa’s influential 1982 track “Planet Rock”— is just one of many that appears in the anthology, which will be released by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings and the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) today. The project is part of the African American Legacy Recordings, a collaboration which seeks to explore musical and oral traditions in the Black community across the United States. The anthology includes 129 tracks on 9 CDs, which are accompanied by a 300–page book designed by Cey Adams, artist and founding creative director of Def Jam records.

“I waited my whole life for an opportunity like this,” says Adams, an artist who played a pivotal role in the development of the visual narrative of hip-hop, designing covers for a host of artists from Run DMC to the Notorious B.I.G. over the years.

“Hip hop is like a brother or sister [to me],” says Adams. “It has been there the whole time. There was never a moment where I was looking up to hip-hop [and saying] ‘Oh my God, look how amazing this is!’ We started out at the same time.”

The Adams-designed tome is filled with essays and quotes penned by prominent critics, historians, and cultural figures, including music writer Naima Cochrane, Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch, who is also the founding director of NMAAHC, and even former President Barack Obama.

“There was a whole committee that was working with me. We had people sourcing the images from around 50 photographers,” says Adams. “I made a lot of creative decisions. But there was a team of people that were helping to source the images [and] write the essay[s].”

Curators at NMAAHC assembled an advisory committee of around 40 musical artists, industry leaders, writers and scholars to create a list of about 900 songs to include in the compendium. To trim the list, a ten-person executive committee—which included Chuck D, MC Lyte, historians Adam Bradley, Cheryl Keyes, Mark Anthony Neal, and industry insiders Bill Adler and Bill Stephney—gathered in Washington, D.C.

“We were all committed to telling the story and preserving this history,” says Dwandalyn Reece, NMAAHC's curator of music and performing arts. “So, [we made] a lot of the decisions, but it was never really an issue. I mean, the hardest thing that we had to decide was those tracks and … having to narrow something down. But it’s just the same kind of thing that we do [while preparing for an exhibition]. If we can only have 300 objects, because we can't have 400, who do you leave out? It's not a value proposition.”

Some songs that the committee had initially selected didn’t make it to the final cut because of licensing issues. For example, there aren’t any songs with Jay-Z listed as the lead artist, and he is only featured as a guest on Foxy Brown’s “I’ll Be.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/1f/c31f2fd1-6d66-4111-baa4-259774c29606/2013_149_1_1_001.jpg)

The anthology includes a host of important tunes, starting with songs from the 1970s such as The Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight.” The 1980s featured tracks include Kurtis Blow’s iconic song “The Breaks” and Whodini’s “Friends.” Later discs contain everything from DMX’s “Ruff Ryders Anthem” to Lil’ Kim and Puff Daddy’s “No Time” to The Notorious B.I.G.’s “Juicy.” Though most of the artists featured in the anthology identify as Black, some white rappers like Beastie Boys, Vanilla Ice and Eminem are also featured.

“In order for hip-hop to be studied properly over the next 40 to 60 years it has to be placed in some type of organizational method or in chronological order,” says 9th Wonder, a producer and member of the executive committee. “Telling the story of how something started in the Bronx as a multicultural [movement], based on immigration [because] the restructuring of the Bronx [made it] multicultural. It's hard for one race to say hip-hop is ours because if you know the history of it [it’s diverse]. You have African diaspora as ours, but the culture was created by many people, and [it needs to] be placed in the canon by these people that know a culture and what it means.”

The anthology speaks to such diversity: All the tracks included were selected for their cultural relevance to communities across the U.S. Though hip-hop emerged as a genre in the Bronx, the sound proliferated throughout the country, and the anthology reflects this by including artists from different locations, like Georgia’s Outkast and Florida’s 2 Live Crew.

One artist in the collection, 2Pac, even moved from New York and eventually made his way to California. “Another song I like that is on there is Dear Mama from 2Pac,” says Reece. “We looked at this set as not just being for the afficionado or for people who don't understand, don't appreciate or only know the propaganda about hip-hop.”

“Dear Mama” describes 2Pac’s complicated relationship with his mother, Alice Faye Williams. Born as Tupac Shakur in 1971 in Harlem, New York, 2Pac chronicled his life through songs, documenting his experiences in both New York and his adopted home in California. As a child, 2Pac and his mother had a strained relationship because she was raising two kids on her own as a single mother, and she often struggled to make money to support her family. In the song, 2pac rhymes:

But now the road got rough, you're alone

You're tryin' to raise two bad kids on your own

And there's no way I can pay you back

But my plan is to show you that I understand

You are appreciated

Adams—who was born in Harlem, New York and raised in Jamacia, Queens—says that many hip-hop tracks reflect the hardships that people experienced and the multifaceted relationships that individuals have within their communities. “New York is a tough place, but if you are an artist, [either a] recording artist [or a] musician that's who you are. It's in the blood, you know, there is nothing else. You have no choice but to [express] who you are.”

The stories that these artists tell help document cultural changes and communal narratives, which is something that many Black music genres such as funk, jazz, gospel and afrobeats all have in common. This isn’t a mere coincidence: The oral tradition remains an important aspect of the African diaspora, and Black communities have preserved their narratives through word of mouth for years, as historian Janice D. Hamlet pointed out in a 2011 issue of Black History Bulletin.

Now, codifying such histories in a written form is giving the Smithsonian the opportunity to archive them in more textually grounded way.

“It's a reflection of who we are,” says Reece. “The history is more serious than people realize. When you take something like hip-hop and give it the Smithsonian treatment [it has an effect.] I don’t like to say canonize. We're not canonizing. Not intentionally, but in the broader landscape there is a certain kind of value we're bringing as a public institution to validating and valuing this cultural art form, in a way that it means something to people.”

Furthermore, by couching these narratives in musical scholarship and personal anecdotes, it gives curators the opportunity to contextualize hip-hop in a broader cultural setting that a casual listener wouldn’t get from just hearing a CD or streaming a song on YouTube.

“Our agenda is to tell the American story through the African American lens,” says Reece. “Hip-hop is just as American as anything else, and this filters through the entire culture of society. There's so much if you take it from a macro level to really study it, its influence, bridging culture and commerce.”

Such a mission may be particularly pertinent to African American communities because so much of Black history has been lost to the vestiges of colonialism. In a world where enslaved people were unable to keep written records or remain connected to their families, many personal histories have been forgotten. “You know a lot of [African Americans] don't know where we come from,” says 9th Wonder. “We don’t know what tribe we come from, we all know what country we come from, or a region we come from in the motherland. We know nothing. A lot of us [are] walking around with new names. We don't know what our real family name is. When it comes to this music and what we've accomplished in it, [we] at least know that much, [even] if we can't know anything else.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)