Children Used to Learn About Death and Damnation With Their ABCs

In 19th-century New England, the books that taught kids how to read had a Puritanical morbidity to them

:focal(1197x593:1198x594)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/68/16/68166818-2aa3-4cd4-9a11-1502e8e1fca5/primer_skeleton.jpg)

Do you remember the books that helped you learn to read—maybe Dick and Jane, Dr. Seuss, or Clifford the Big Red Dog? No matter the answer, odds are your experience was very different from most Protestant children living in early America because your books probably did not contain a discussion of your imminent death.

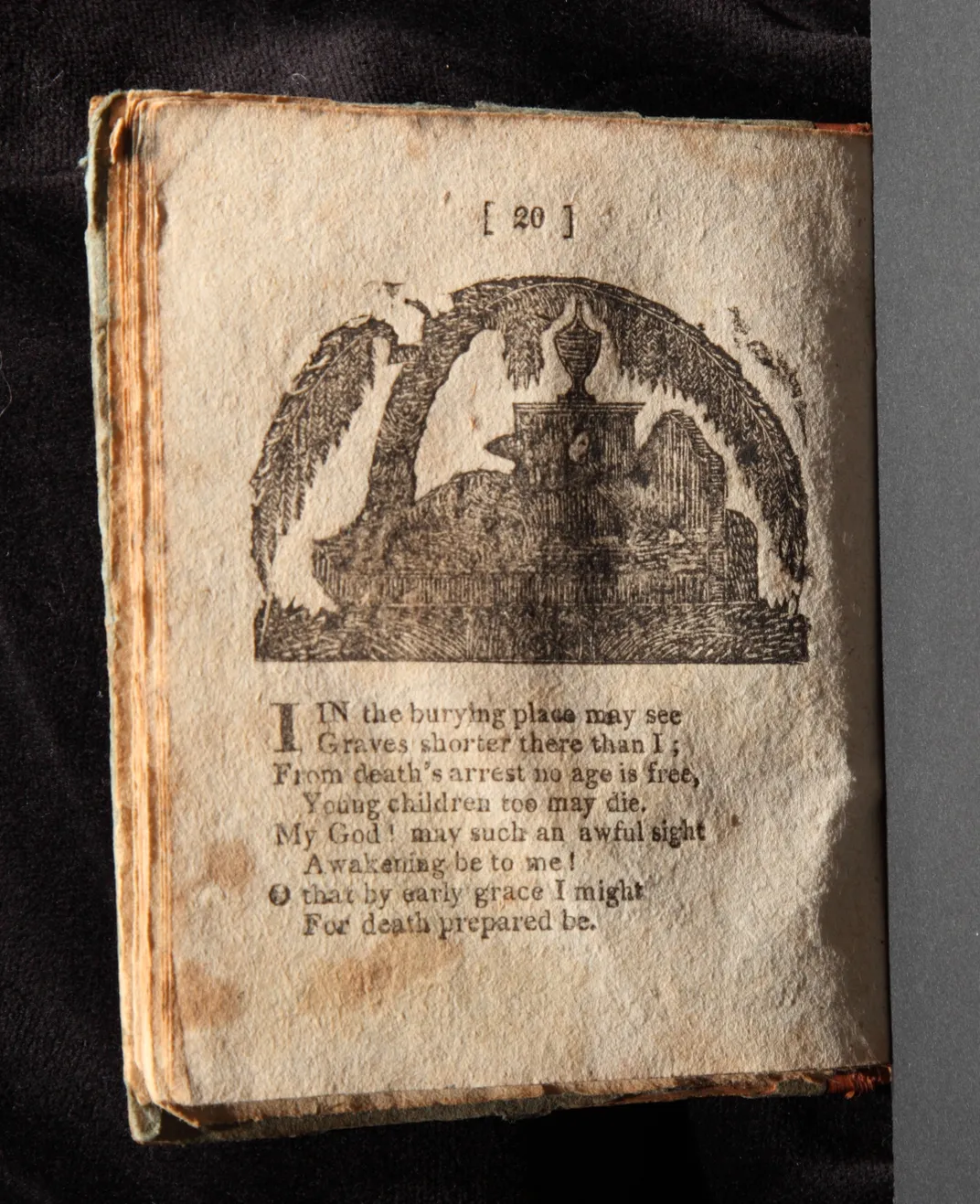

Instead of an archaic version of See Spot Run, many youths in the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries learned to read from sentences like: "From death's arrest no age is free/Young children too may die."

This catchy warning of childhood death comes from a little oak-bound book called the New England Primer. We have three of these books in the education collection, printed in 1808, 1811 and 1813. New England Primers, first printed in Boston in the 1680s, were extremely popular texts not only in New England but throughout the United States. The primers prepared young children to read the Bible because reading the word of God for oneself was the ultimate goal of literacy for many Christian Americans at this time.

New England Primers were ubiquitous in colonial America and in the early Republic. Although estimates vary, children's literature scholar David Cohen reports that, between 1680 and 1830, printers produced as many as eight million copies of the books. So for at least 150 years, millions of young American children learned their ABCs alongside repeated reminders of their impending deaths.

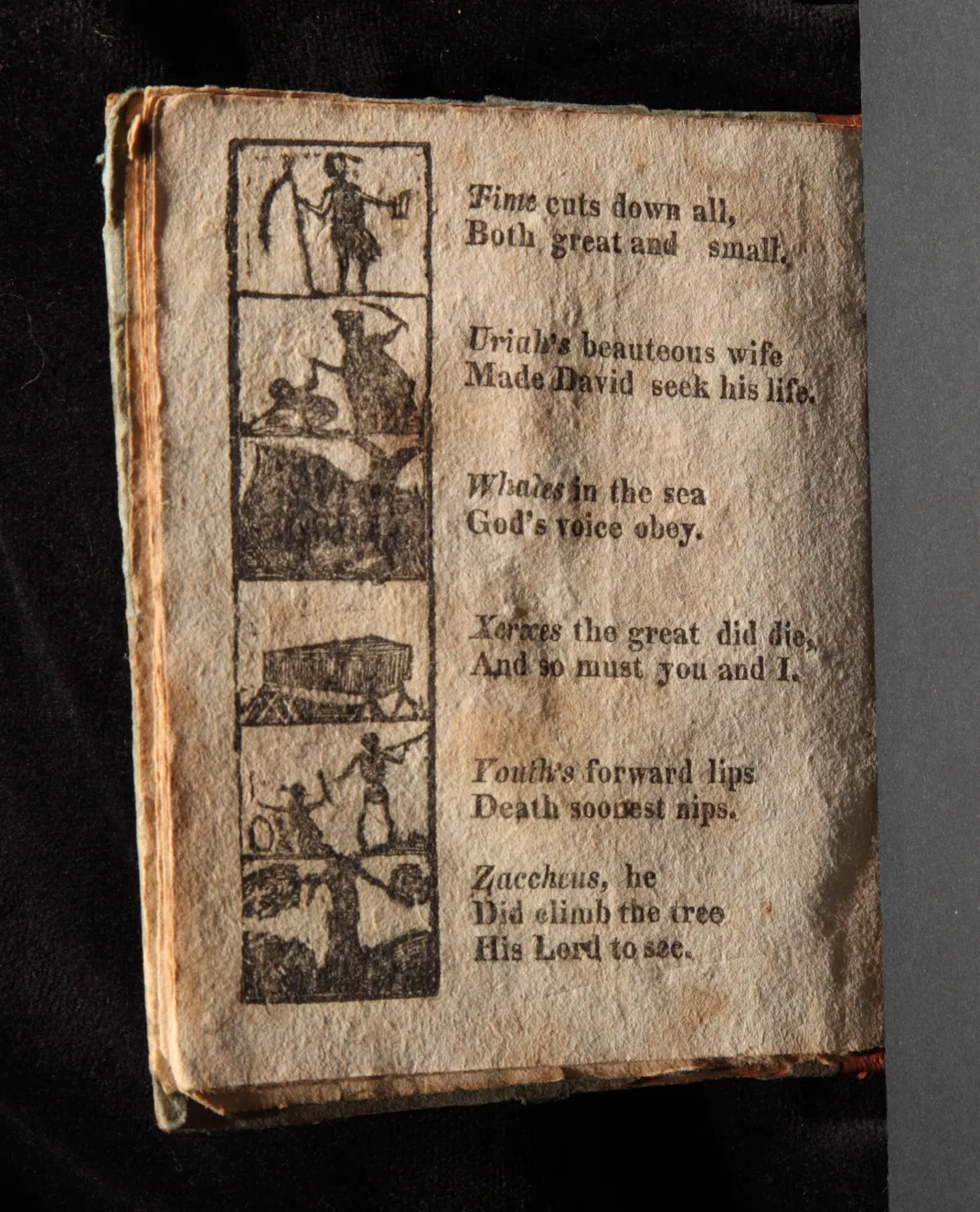

Take, for example, this page from one of the primers in our collections. In introducing six letters, it manages to invoke mortality four times, with two anthropomorphic representations of Death, one biblical murder and one coffin. Lest any child have forgotten that death forever lies in wait, mastering the letter "T" entails learning that "Time cuts down all,/Both great and small," and "Y" teaches that "Youth's forward lips/Death soonest nips."

New England Primers went through many different editions. Specific details changed, but the basic format remained relatively constant: each book had a pictorial alphabet like the one in the photograph above, lists of words with increasing numbers of syllables ("age" to "a-bom-i-na-tion," for example), prayers for children, and copious and unflinching mentions of death.

All the primers in our collection, for example, use the couplet "Xerxes the great did die/And so must you and I" (although, in fairness, "X" was a hard letter to illustrate before "xylophone" entered the English lexicon). Another of our primers devotes half a page to a meditation "On Life and Death," dominated by a woodcut illustration of a weapon-wielding skeleton. Others detailed the death of John Rogers, the Protestant martyr who was burned alive in 1555 by the Catholic Queen Mary I of England, or contained various versions of the catechism.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/68/16/68166818-2aa3-4cd4-9a11-1502e8e1fca5/primer_skeleton.jpg)

Why such a focus on death? It partially stems from high childhood mortality rates in an age before vaccines and modern medicine, when contagious diseases like scarlet fever, measles and whooping cough ran rampant. The emphasis can also be explained in part by the changing attitude toward death in the time of the primers' popularity, an attitude that increasingly saw death not as a morbid end but instead as a positive event that allowed righteous souls to pass into eternal paradise. This change can be seen not only in children's books like the primers but in many places, such as gravestones that started to carry messages celebrating the fate of the soul after death.

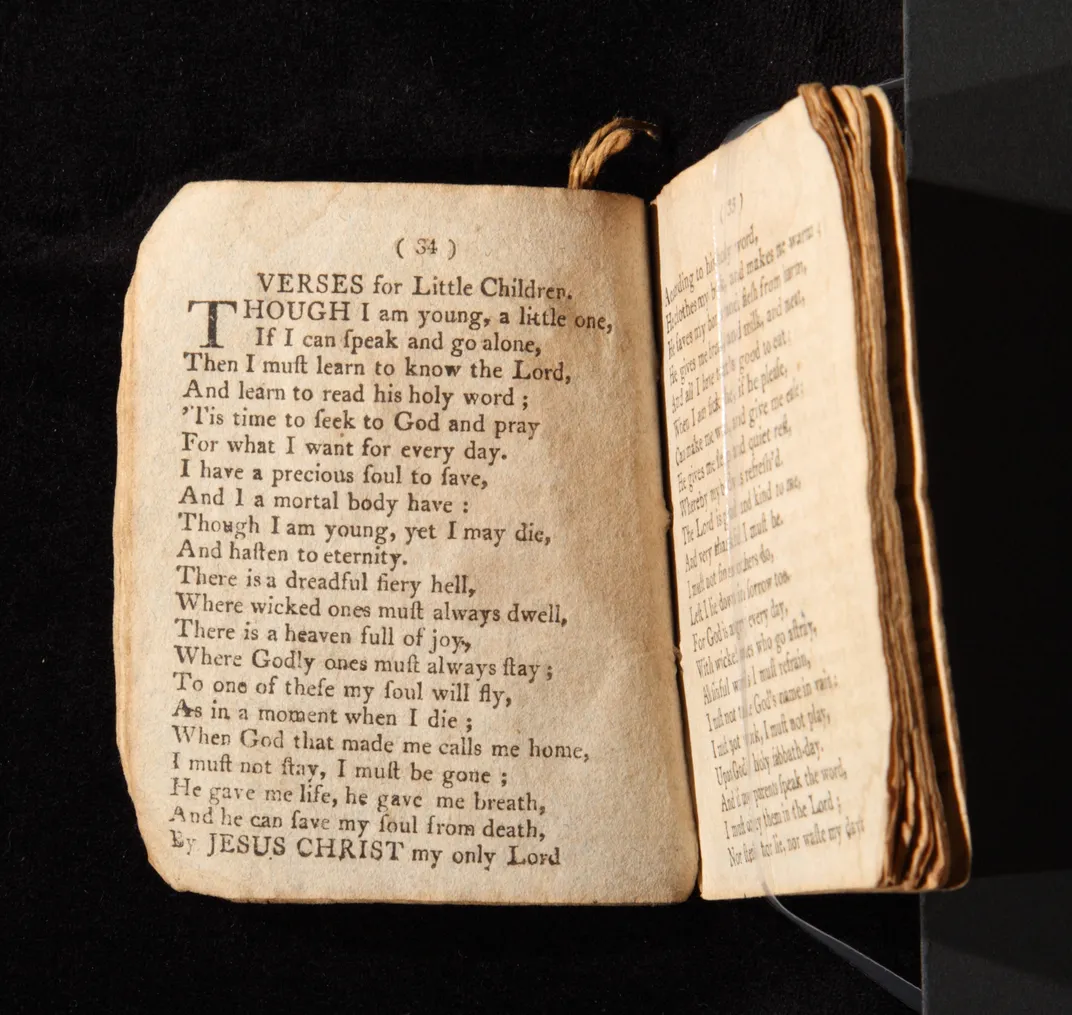

But the main reason for the seeming obsession with death in the New England Primer lies with the religious inclinations of the book, which was written primarily for the Protestant populations of New England and reflects a Puritan religious ideology. Puritans believed that children were born, as our 1813 primer states, with "foolishness . . . bound up" in their hearts, but still held that even small children were just as responsible as adults when it came to living godly, sinless lives in order to escape divine punishment. This view is articulated in a primer's "Verses for Little Children":

What we might view now as normal childhood behavior was, to the target audience of the New England Primers, sure to get a child sent to hell when the next fever swept through town. Impressing upon children the shortness of life and the importance of avoiding "dreadful fiery hell" was thus a principal goal of childhood education.

Emma Hastings completed an internship in the Division of Home and Community Life with curator Debbie Schaefer-Jacobs in summer 2017. She is a senior at Yale University.

This article originally appeared on O Say Can You See, the blog of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Read more back-to-school related posts about the history of school supplies, Catholic school uniforms, the 19th-century equivalent of “My Child is an Honor School Student” bumper stickers, and the evolution of school safety.