Ai Weiwei Takes Over the Smithsonian: “According to What?” Opens at the Hirshhorn

The museum hosts the U.S. premier of a blockbuster show from the controversial artist

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20121003082036Colored_Vases_Thumbnail.jpg)

“Ai Weiwei is taking over the Smithsonian,” joked the Hirshhorn’s chief curator Kerry Brougher about the Chinese artist’s new exhibition at the museum. With an installation outside the museum, a piece at the Sackler Gallery and now a sprawling, multi-level show at the Hirshhorn, Ai Weiwei has accomplished a lot for an artist forbidden to travel from his home country.

Considering it took 38 tons of steel rebar, 3,200 porcelain crabs and millions of crystals, as well as a Department of State liaison to get Ai Weiwei’s “According to What?” installed throughout three floors of the museum, visitors could be forgiven for having the impression that the artist is, in fact, taking over. The artist’s absence and his own powerlessness against the Chinese state stands in high contrast to the power he commands across the Western art world. And this, his newest show, building off of a 2009 exhibit at Japan’s Mori Art Museum, continues to challenge notions of cultural and political power in Ai’s signature style.

A mix of photography, video and sculpture welcomes visitors into the world of an internationally famous but severely restricted artist. When the museum began planning with the Mori Art Museum to bring this show to the States for the first time, says Brougher, Ai was still just an emerging artist. “At that time, we had no idea what was going to follow.”

The Sichuan Earthquake had occurred in May, 2008. That December, Ai joined another artist’s investigation into the devastation, including compiling a list of all the students killed, largely due to poor construction. Ai continued to travel around the world until tensions with the Chinese state rose to a boiling point in 2011: Ai’s just-completed studio in Shanghai was abruptly demolished in a single day in January. Then came Ai’s mysterious arrest in April. He was held for 81 days without being charged. Though he was eventually released, he is still unable to leave China.

None of this has stopped the artist from producing new work for new audiences or collaborating with both the Mori Art Museum and the Hirshhorn Museum. Though Ai spent formative years in New York City, viewing the work of famous artists including Marcel Duchamp and Jasper Johns (whose 1971 painting “According to What” lent the new show its title) and his work has been shown there before, curators say the decision to bring the exhibit to Washington, D.C. was intentional. Director of the Hirshhorn, Richard Koshalek says, “It’s very important for him that this exhibition is in Washington, D.C. It’s not in New York. It’s not in L.A. It’s not in Chicago.” Speaking to Ai’s role as an activist and agitator, Koshalek says D.C. offers an international community, an audience of diplomats and a city concerned with freedom of expression, not just in China, but all over the world.

The decision seems significant for Ai’s career, as well. Though his inspiration in New York City, Marcel Duchamp, delighted in upsetting the art institution by presenting urinals and bicycle wheels atop a stool, his work did not put him at odds with a government. When Ai crafts a multi-limbed sculpture of wooden stools and declares, “I make the useful become not useful,” there is more at work than a flippant aesthetic challenge. His work will always be read as a middle finger (sometimes it literally is) to the Chinese state.

The New York Times said it best when it wrote, “So much attention has been paid to Ai Weiwei the Chinese rebel that it seems to have eclipsed Ai Weiwei the artist.”

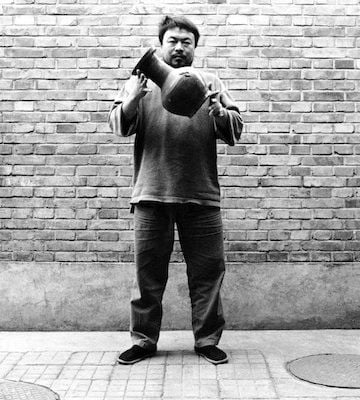

His famous series Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (above) begun in 1995 is no longer just a comment on the essentialization of Chinese culture as a static, ancient form. Instead, dropping a vase here is the same as throwing down the gauntlet, challenging the elaborate staging of Chinese history and culture, according to the Communist Party.

Newer work supports this interpretation, as well. More than 3,000 porcelain crabs titled “He Xie,” confuse the term for river crabs for the word “harmonious,” from the Communist Party’s slogan, “the realization of a harmonious society.” The term is now used online as slang to refer to China’s rampant censorship.

In his artist statement, Ai writes, “I have lived with political struggle since birth. As a poet, my father tried to act as an individual, but he was treated as an enemy of the state.” Reflecting on his own recent clashes with the state, he continues, “Going through these events allowed me to rethink my art and the activities necessary for an artist. I re-evaluated different forms of expression and how considerations of aesthetics should relate to morality and philosophy.”

Art and politics, aesthetics and ethics can never truly be separated, but with this new show, Ai says they are one in the same. And he says it without hesitation.

Snake Ceiling commemorates the more than 5,000 students killed in the Sichuan earthquake with a giant snake constructed from gray and green backpacks. At once literal and fantastical, the work is an efficient indictment of a culture and government that failed to protect its students.

Perhaps the most enigmatic work in the whole show, is the sparkling Cube Light with its strands of light-catching crystals.The museum acquired it for its permanent collection. Less overt than some of the other works, the piece is a fitting acquisition to represent a man who resists being defined as simply an artist or an activist.

Ai ends his statement saying, “As an artist, I value other artists’ efforts to challenge the definition of beauty, goodness, and the will of the times. These roles cannot be separated. Maybe I’m just an undercover artist in the disguise of a dissident; I couldn’t care less about the implications.”

“According to What?” opens at the Hirshhorn Museum October 7 and runs through February 24, 2013, before heading to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Miami Art Museum and the Brooklyn Museum.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)