This Ace Aviatrix Learned to Fly Even Though Orville Wright Refused to Teach Her

With flint and derring-do, the early 20th century pilot Ruth Law ruled American skies

:focal(1000x323:1001x324)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/47/29/4729fb8e-f5a5-4151-8aa6-f154de508a6c/nasm-si-2009-22214.jpg)

On November 20, 1916, a small Curtiss pusher biplane was nearly out of gas and gliding. The pilot, freezing in an open-air seat, could hardly see through the thick fog and worried about crashing into the brass band playing below on New York's Governor's Island.

"Little girl, you beat them all," General Leonard Wood said to Ruth Law when she safely landed—missing the band—and clambered out, smiling underneath her leather flight helmet. A crowd shouted and cheered. Swaddled in four layers of leather and wool, the 28-year-old Law had just smashed the American cross-country flight record with her 590-mile flight from Chicago to Hornell, New York. The celebrated final leg, to New York City, brought her total miles flown to 884. A hero of early aviation, Law defied Orville Wright, broke records and inspired Amelia Earhart.

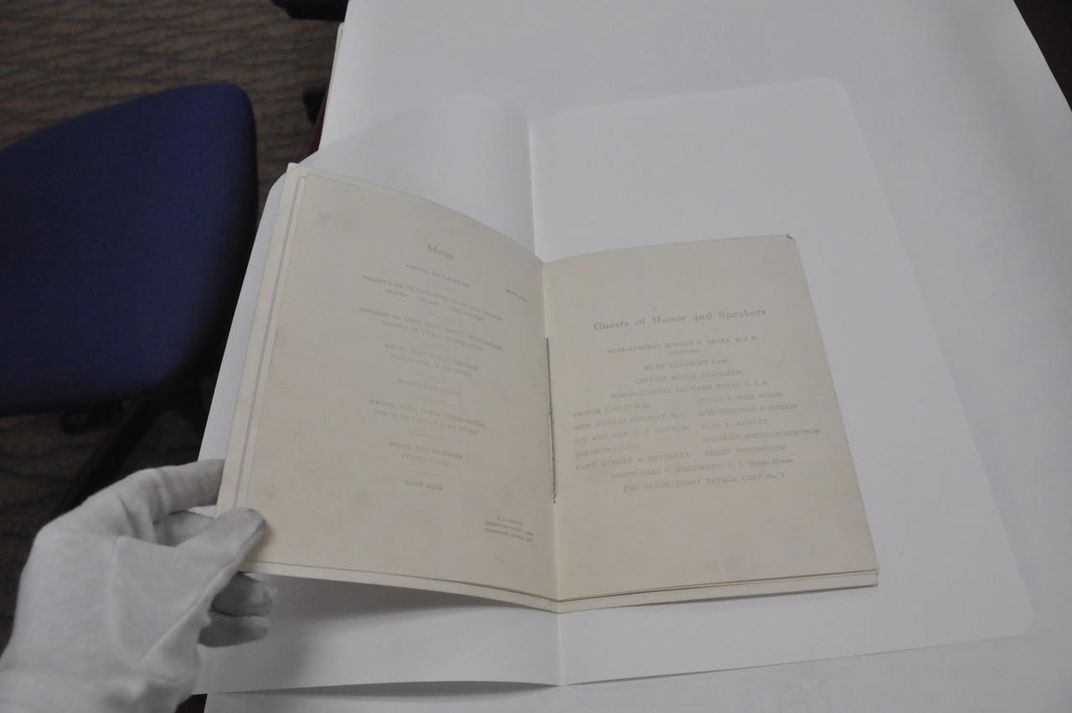

She also kept her own, detailed scrapbook, which is in the archives of theSmithsonian's National Air and Space Museum. It's kept in an oversized box—if you request to see it, it comes to you on a wheeled cart—its pages separated with white tissue paper. Turning each giant page, you see the mementoes Law kept—a menu, a passport, a war bonds leaflet—as well as the hundreds of articles she compiled about her own career, when reporters called her Angel Ruth, and Queen of the Aces. Law was a novelty.

In Law's time, "flying was so different, it didn't matter who was in the cockpit," says the museum's curator of aeronautics Dorothy Cochrane, "The public was excited to see women—they were accepting of it, they were not shaming these women for going up. It certainly sold newspapers." That later changed, she added, women were not welcomed for piloting duties.

Law became intrigued by flying because of her brother, the daredevil Rodman Law. As a child, Ruth kept up with her brother physically, climbing telephone poles and riding fast horses.

Family ties were common in early aviation, Cochrane says, citing the Stinson siblings and the Wright brothers as well as the Laws. "There's not a large community," she says, "so when one becomes enamored of it, the trait to do this sort of thing is in the family obviously. And these women felt secure enough to get out there and do it just as their brothers did."

In 1912, Law asked Orville Wright for lessons. He refused, she said, because he thought women weren't mechanically inclined.

Law, however, was quite mechanically adept, says Barbara Ganson, a professor of history at Florida Atlantic University, and the author of the forthcoming Lady Daredevils, American Women And Early Flight: "She did her own maintenance. She would just take her magneto apart." In a scrapbooked article from 1912, a reporter wrote that "the slightest change in the sound of the whirring propellers instantly warns [Law] of danger. . .She pays strict attention not only to the working parts but also to the tension of the rods and braces which bind the planes together."

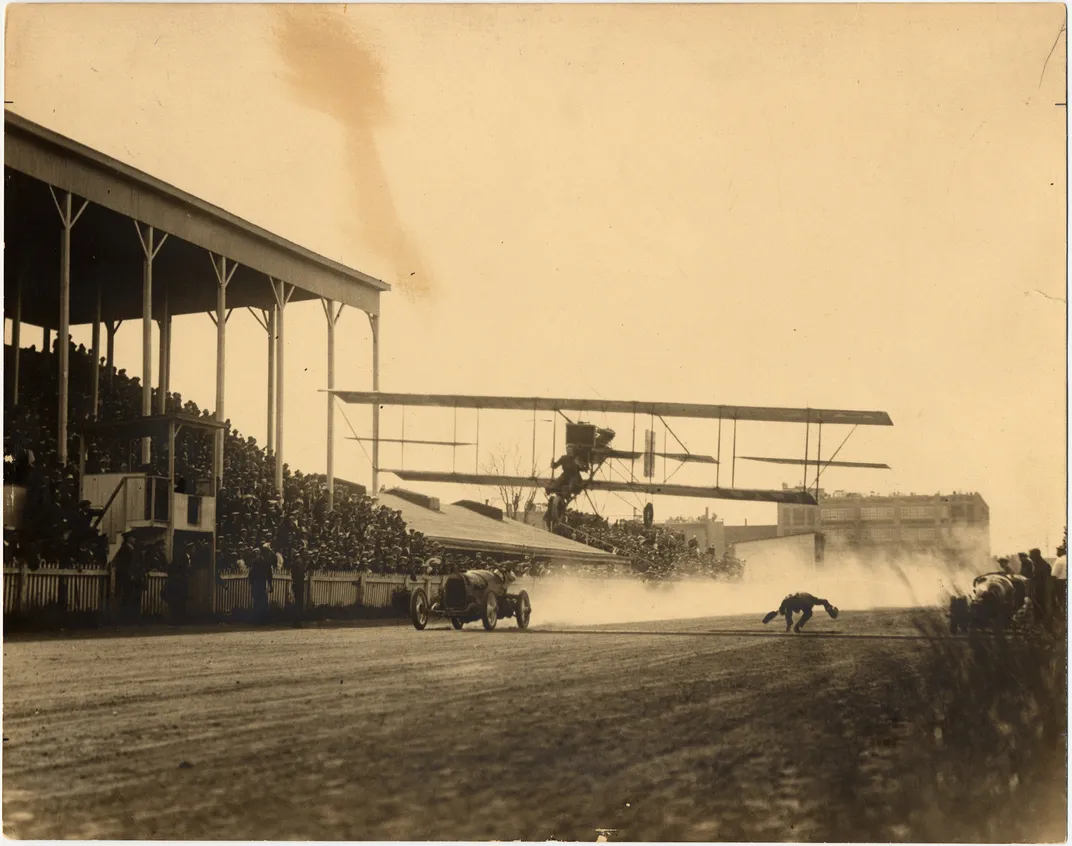

Wright's edict didn't deter Law, anyway. "The surest way to make me do a thing is to tell me I can't do it," she wrote in 1921. Wright did sell her a plane, at least, and Law found an instructor. She learned in three weeks, and began working right away at fairs and air shows as an exhibition pilot. She practiced tricks, looping the loop in 1915.

But it was that 1916 cross-country flight that established Law as a pioneering aviatrix, aviatrice, or aviatress, as women pilots were called. Did fewer women fly because men called it dangerous?

"Just like the ballot, you know," Law said, four years before women would win the right to vote. "Neither one is dangerous when handled properly." Robert Peary and Roald Amundsen toasted her. Law flew around the Statue of Liberty when in December of 1916; President Woodrow Wilson gave a signal, and the statue was illuminated for the first time ever. Circling around it, lights on Law's plane spelled out L-I-B-E-R-T-Y, and magnesium flares made golden waves behind her in the dark.

Law, and other women pilots of the era, possessed special nerve, says Ganson. "What draws them into it, and makes them willing to take that risk? It was a time when aviation was quite deadly." As Law wrote in an article she preserved in her scrapbook, wearing a seatbelt was considered "a bit cowardly."

Law sailed for Europe in 1917 to learn more about warplanes. "She did her own things that she valued," says Ganson. "And that was a time when the United States was behind basically what the Europeans were doing in terms of embracing manufacturing."

Law returned from her trip with a Belgian police dog named Poilu, a trench veteran who wore his own metal helmet and sat with her in the cockpit. But Law saw less action than the dog, because the U.S. army wouldn't let her fly. She wished she could; she wrote that if Wilson told her to "go get the Kaiser," she would "be feeling a little remorseful at having to end a life, but for the most part I would be watching my motor, dodging the German planes, jockeying, dipping, darting to the spot where I would release my bombs."

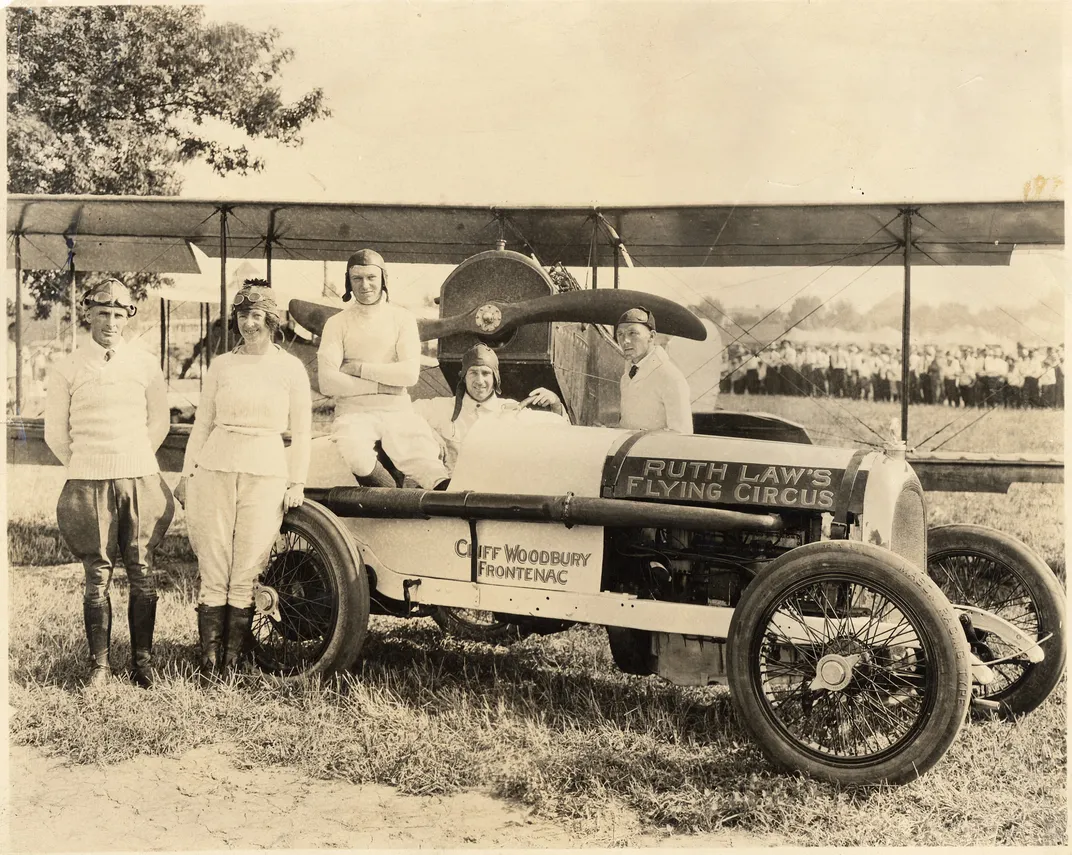

Kept from battle, Law dropped Liberty Bond pamphlets from planes, raised money for the Red Cross and Liberty Loans with exhibitions, and became the first woman authorized to wear a non-commissioned officer’s military uniform. After the war, she inaugurated airmail in the Philippines, and starred in Ruth Law's Flying Circus, performing aerial cartwheels and wing-walking. She earned a place on a special roster of "Early Birds," pilots who flew before America entered World War 1. Her Early Birds plaque is at Udvar-Hazy.

One morning in 1922, Law woke up and read in the newspaper that her husband and manager, Charles Oliver, had announced her retirement. She stopped flying. Future stunts would be performed with a vacuum cleaner and an oil mop, she said. "In that day and age there was a greater need for riskier types of maneuvers," says Ganson. "It was probably a good time to get out of flying. A lot of pilots do get killed in the early years of flight, because they were all essentially test pilots."

Maybe quitting was a safe decision physically, but by 1932, Law said the lack of flying had caused her to have a nervous breakdown. By then, she'd sold almost all of her flight gear. She saved one propeller—the one from the little Curtiss. She had the scrapbook. She spent her days choosing cacti for a rock garden she tended behind her Los Angeles bungalow, way beneath the clouds.

In 1948, at the National Air and Space Museum, Law traveled to Washington, D.C. to attend a Smithsonian ceremony celebrating the receipt of the Wright brothers' Kitty Hawk plane, honoring the craft of a man who wouldn’t teach her to fly.

She took the train.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/46/e0/46e0beb5-53c6-405e-8ac4-36846530e968/nasm-nasm-9a11969web.jpg)