Here Are 12 Things You Might Miss in the Smithsonian’s New Fossil Hall

Hidden among the dinosaurs and megafauna, are these small details that make “Deep Time” all the more impressive

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/37/bd/37bdaa3f-d01c-4fce-986e-0fe5bd445ba9/nmnh-2019-00504.jpg)

It’s easy to get caught up gazing at the towering dinosaurs in the new fossil hall at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, but the story of our planet’s life history is much more complicated than Tyrannosaurus rex and its cousins.

The exhibition is set up to take visitors on a journey through prehistoric time, hence the hall’s moniker: Deep Time. Covering 4.6 billion years, the show captures what life looked like in the oceans, details how it emerged onto land, and explores all of what life looked like before, during and after the dawn of dinosaurs. The nuance of millions of years of evolution plays out in elaborate works of art, digital displays, tiny dioramas, molds, models and detailed fossils big and small.

It’s tough to catch everything the first—or even second—time around so we've put together a list of things that you might miss, but shouldn't.

Watch a Lizard Decay and a Gecko Catch a Fly

The scientific practice of recreating the fossilization process is called taphonomy. In the new Deep Time exhibition, you can watch it unfold before your eyes with time-lapse imaging of a decomposing lizard. Over the course of a little more than a year, you can see the lizard’s body bloat up, get devoured by flies and maggots, and eventually disintegrate down to its bare bones. (Be sure to move the cursor ever-so-slowly so you can see a gecko sneak onto the carcass to catch flies for dinner.)

Featured behind the interactive touch screen video, you can see the fossil of an early synapsid, Ophiacodon uniformis. Replicating the fossilization process helps researchers learn more about the creature’s final moments and the earliest stages of fossilization.

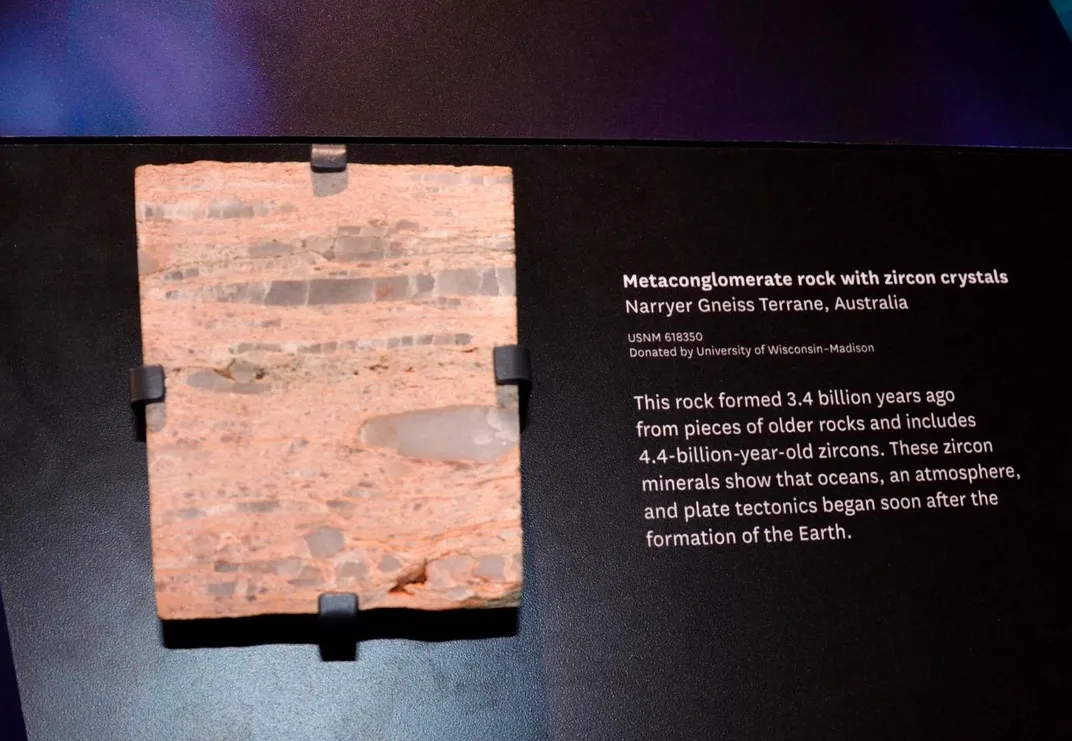

Touch Something 4.4 Billion Years Old

To tell the story of the history of life, you have to start at the very, very beginning. Before life could inhabit Earth, the planet had to become habitable.

On display is a 3.4 billion-year-old metaconglomerate rock with 4.4 billion-year-old zircon bits embedded inside it. Minerals in the zircon show a time when Earth’s oceans, atmosphere and plate tectonics began. At that time, the ingredients for life on Earth were merely microscopic, organic material found in the early oceans. Today, those same materials still exist, but only in harsh environments like hot springs.

Charles Darwin's Book Holds a Secret

Adorning several walls of the hall in colorful typeface is the elegant quote: “From so simple a beginning, endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.” It is the last sentence from On the Origin of Species written by the famed English naturalist Charles Darwin.

The quote is a unifying theme of the hall and centers around the idea that life on Earth is forever changing, was changing in the past and will change again. That’s also why a bronze statue of Charles Darwin sits at the center of the exhibition. With his notebook in hand, the sculpture of Darwin is seated on a bench, as if he's just exhausted himself touring the show. Sit down beside him and take a look at the open page of his journal. There you'll find recreated his first-ever sketch that he made of his “tree of life.” With ancient creatures branching off to modern-day animals, this was the catalytic moment when Darwin realized with all certainty that all plants and animals are related. At the top of the journal page, Darwin wrote with great authority: “I think.”

Another curiosity? The bird on Darwin's shoulder is in fact a finch, the species he studied to illustrate his theory of evolution.

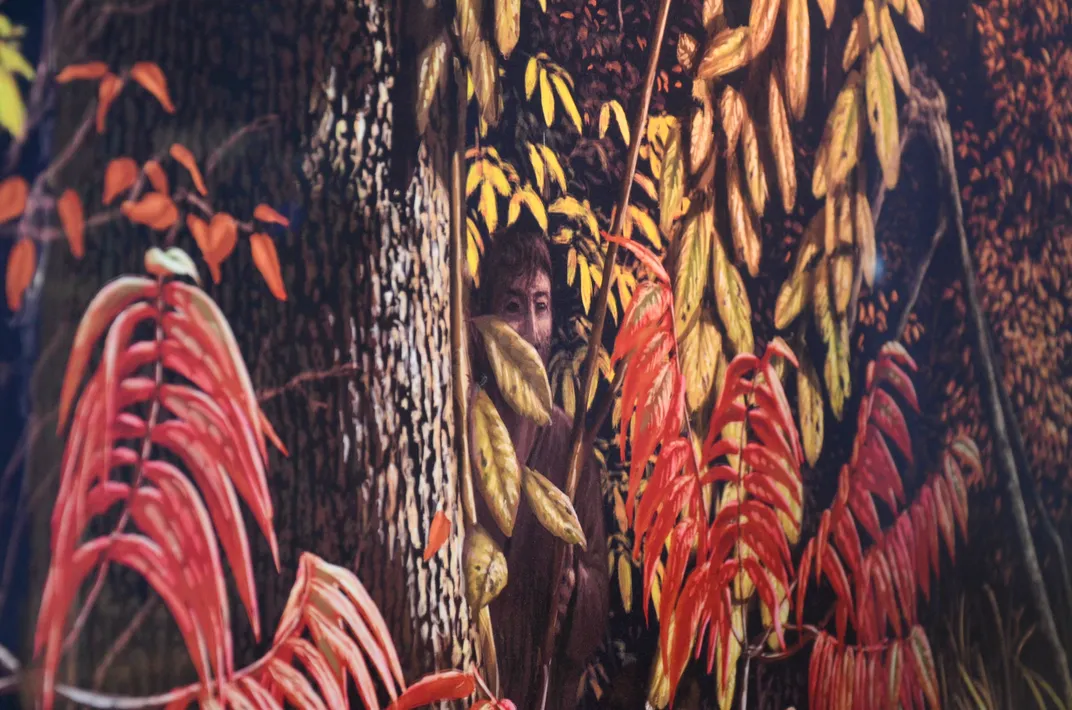

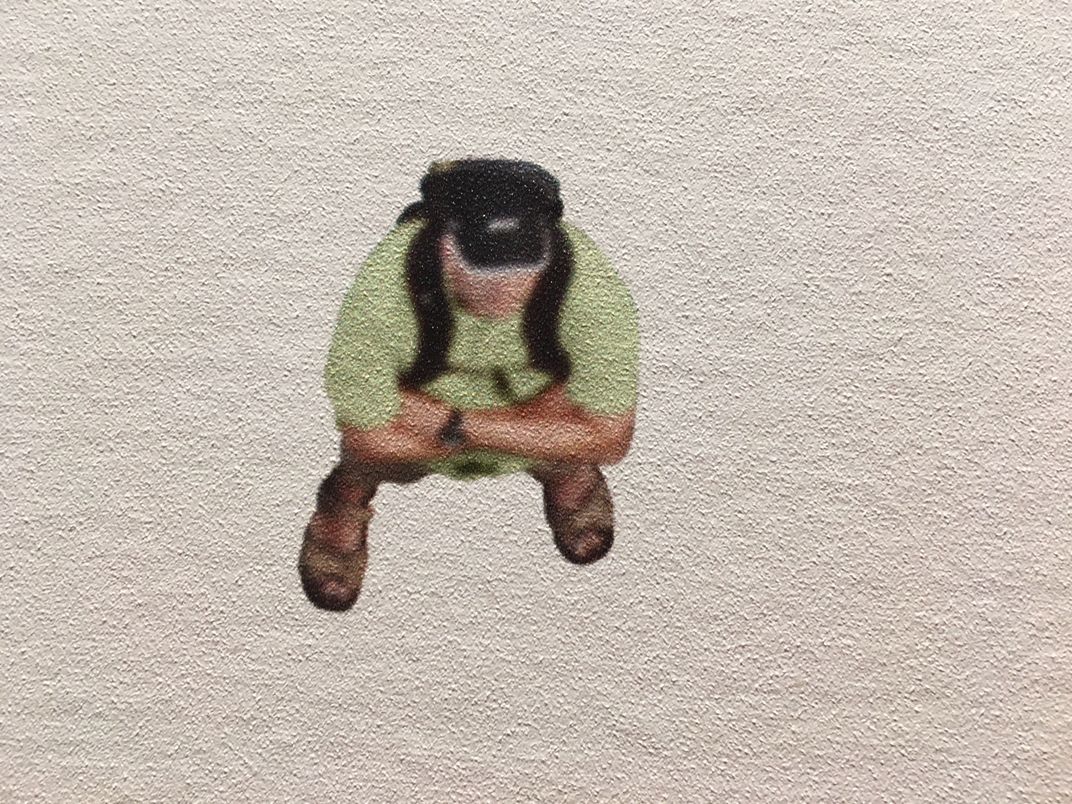

A Man in the Bushes Hunts Down a Mastadon

The hall is set up to take you through time. Right around the exhibition’s entrance, you can find displays featuring early humans. By around 13,000 years ago, our ancestors were on every continent, sharing the Ice Age-era Earth with megafauna like the mastodon.

A bronze statue of Homo sapiens appears pathetically diminutive against the massive mastodon skeleton, but if you look closely at the intricate artwork behind the mastodon, on the wall, you will find one of our ancient cousins peering out from the brush at the great beast.

A Frog and a Salamander Swimming in a Dino Footprint

During the Cretaceous period, flowering plants started to take root and dinosaurs lived in a brilliantly biodiverse ecosystem. Right next to T. rex devouring a Triceratops, there’s an illustration of a dinosaur footprint filled with water. In the tiny pool, swims a frog and a salamander.

By collecting microfossils, or super small skeletal remains, at dig sites, researchers know that prehistoric amphibians shared the ecosystems that dinosaurs inhabited. A teeny prehistoric salamander jaw in the nearby display case dates to the age of the dinos.

“These are critical tools in the study of dinosaurs,” the display text points out, quoting the museum's curator of dinosaurs Matthew Carrano. “I’m especially interested in finding small fossils from many different species, so I can understand more about the whole ecosystem.”

It’s Not a Glitch in the Matrix: That Bronze Reptile Is Pixelated

A lot of times when researchers find the remains of an ancient organism, they have to work backward to figure out exactly what it was. That process can get really tricky if they only have one or two fossilized body parts to go off of. That’s the case with Steropodon galmani, or what researchers suspect is an early mammal. Because they don’t have all the details filled in, they decided to display it as a work in progress.

We may not know much about what Steropodon galmani looked like, but we do know that many early mammals did something they’re modern counterparts can’t: lay eggs. You’ll notice the pixelated rat-like statue is guarding a nest.

It’s a Messy World—The Dioramas Have Dung Piles

A major goal for the team behind the new exhibition was making sure the displays were as realistic as possible. That meant major innovations when it came to how to pose the skeletons and how to provide more context about the environment the animals inhabited. And that meant making things a little messier. Earth wasn’t a completely pristine, luscious utopia before humans came along and life has always been a little dirty. When putting the final touches on the diorama models together, Smithsonian researchers noticed something was missing: poop.

Look closely at these tiny worlds and yep, your eyes don’t deceive you. Those are poo piles.

And You Can Read About Dino Poop Before You Go

Ever wonder what T. rex poop looked like? It might not be the most glamorous feature of the hall, but researchers learn a lot about diet and habitat from fossilized excrement, or coprolites as they’re technically called, like T. rex’s.

In this particular coprolite cast, paleontologists found crushed, undigested bone. That tells researchers that T. rex chewed its food, rather than swallowing it whole.

You can read all about it in a strategically placed location: on the walls as you wait in line for the bathroom.

Is That a Bug or a Leaf—or Both?

One of the coolest features that modern insects have evolved is the creative ways that they blend into their surroundings using physical camouflage. If you look closely, you’ll see a prehistoric bug, the Scorpionfly, Juracimbrophlebia ginkofolia, next to an early Ginkgo tree relative, Yimaia capituliformis. Both are estimated to exist between 157 to 161 million years ago.

You can also catch early evidence of eyespots on the wings of a Kalligramma lacewing butterfly. Scientists suspect eyespots first evolved in Jurassic lacewings and then a second time in modern butterflies.

This Huge Prehistoric Fish Ate a Slightly Less Huge Fish

This fossil might have you seeing double: A massive prehistoric fish, Xiphactinus audax, devoured a still impressively large, Thryptodus zitteli. Both then met their fate and became fossilized in incredible detail. These two teleosts, or relatives of bony-tongues fish, lived between 89 and 90 million years ago.

Nearby you’ll even see three animals and two meals in one fossil. A mosasaur, specifically Tylosaurus proriger, ate a Plesiosaur as evidenced by bones found within the mosasaur’s stomach. That’s not all: The Plesiosaur also seemed to have a recent dinner, and researchers found smaller bones from a third unknown species in its stomach. (All three were fossilized in a Russian nesting doll of last meals, you could say.)

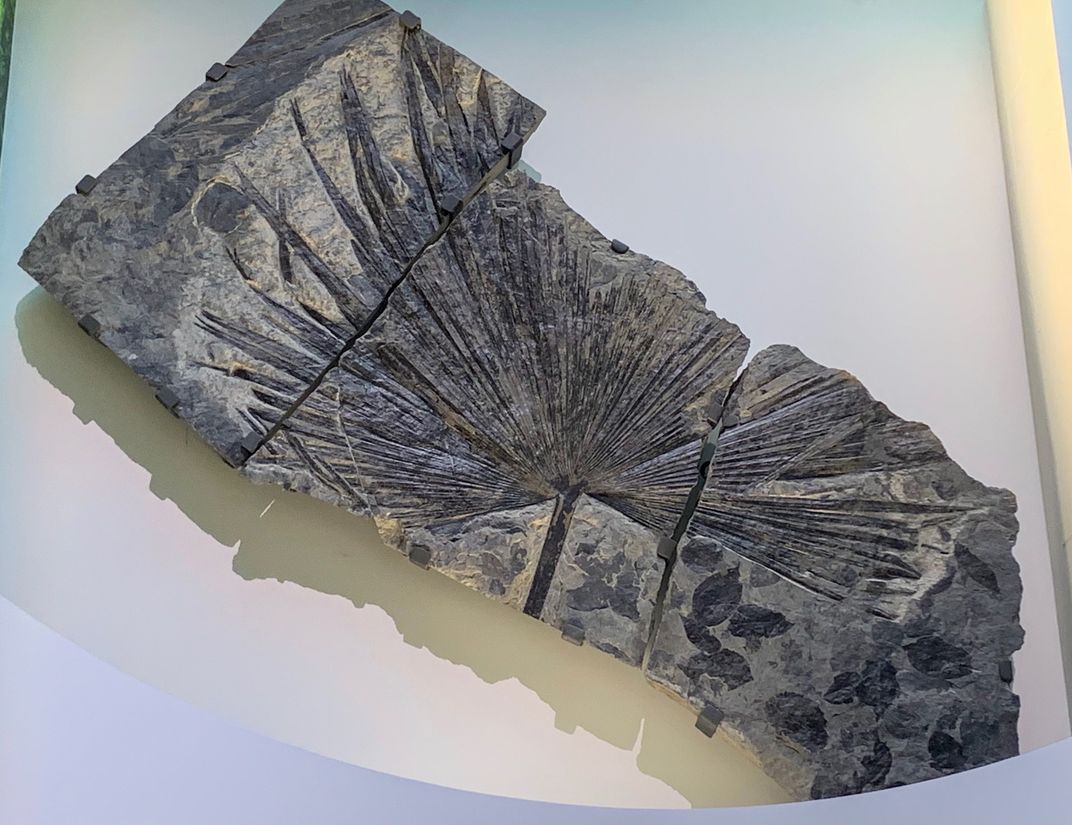

That Palm Leaf Fossil Was Found in Alaska

The new fossil hall isn’t just about dinosaurs—you’ll find fossils of plants, insects and more, too. It’s all part of the overarching story the researchers behind the exhibition are trying to tell: that everything on our planet is interconnected and always changing.

Yes, fossils of tropical plants—and even crocodiles—can be found in Alaska. About 60 million years ago, Alaska was covered in dense, wet forest. The estimated 50-million- to 57-million-year-old giant palm leaf poised above other rainforest foliage was found in what’s now Petersburg Borough, Alaska. Sure, Earth’s climate may have been much warmer than it is today, but that doesn’t mean we can relax and kick back.

As several displays in the hall explain, today’s climate change is happening at an “extremely fast pace” and “humans are the cause.” And just because climate change has happened before doesn’t mean we humans will survive it, which is why there is a section of the hall dedicated to solutions.

The Big Picture: How Rapidly the Human Population Has Grown

The history of Earth and all life on it is also our history. Our actions matter and what we do has an immense effect on the planet. As the exhibition explains, the human population is “three times larger than it was in 1950” and we use “five times as much energy.”

Along the wall, screens display videos about climate change solutions happening in communities around the world. Behind those, you’ll notice that the wall paper is covered with bird’s eye view photos of people that gradually get more numerous and densely spaced from the right side of the wall to the left. That’s not just a cool design element; it’s a precise depiction of how the human population has grown rapidly over time.

But it conveys a message of hope: “We are causing rapid, unprecedented change to our planet. But there is hope—we can adapt, innovate, and collaborate to leave a positive legacy.”

Listen to the premiere episode of season 4 of Sidedoor, a podcast from the Smithsonian, which looks at how scientists O.C. Marsh and Edward Cope went from good friends who named species after each other to the bitterest of enemies who eventually ruined each other's lives and careers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rachael.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rachael.png)