Why Artists Have so Much Trouble Painting Lightning

A new study compares painted versus photographed depictions of lightning bolts’ offshooting branches

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2a/4d/2a4d3a5e-ab71-460e-847b-00109c77383e/f3large.jpg)

Photography has long been touted as a medium unparalleled in its objectivity. As theorist Susan Sontag wrote in the seminal text On Photography, “Photographed images do not seem to be statements about the world so much as pieces of it, miniatures of reality that anyone can make or acquire.”

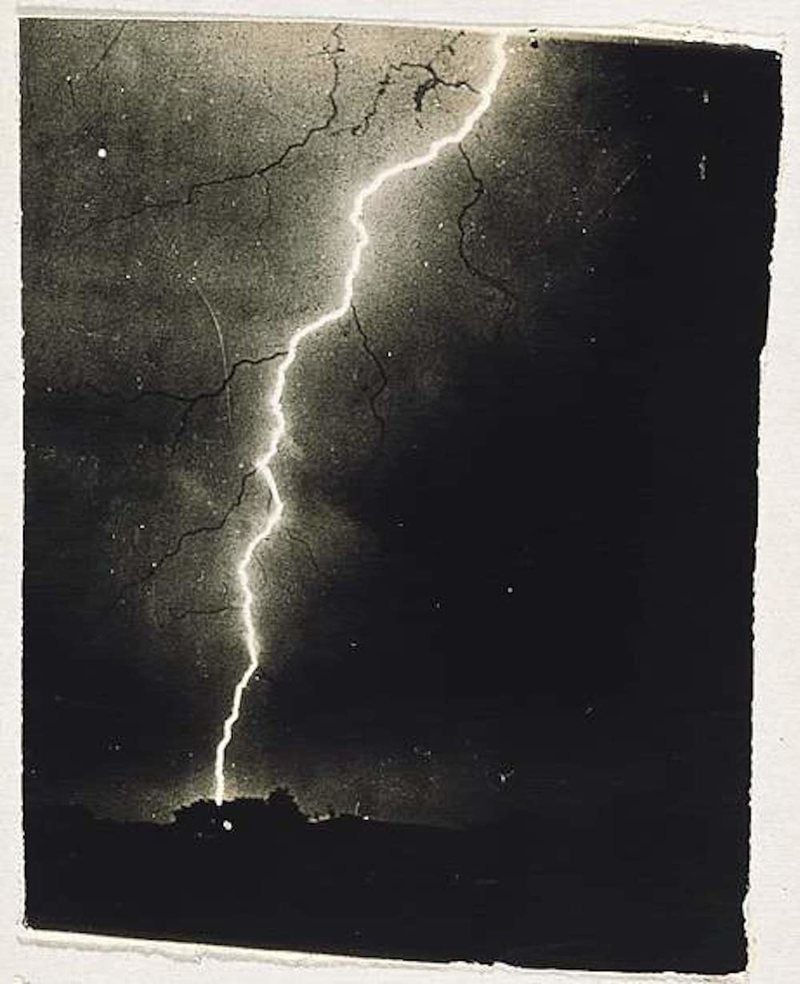

While Philadelphian William Jennings worked as a photographer roughly a century before On Photography was published, his goal of “capturing phenomena the human eye cannot accurately see without mechanical assistance,” as noted by Harvard Art Museums’ Laura Turner Igoe, closely aligns with Sontag’s understanding of the medium.

Now, researchers from Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest have drawn inspiration from Jennings’ best-known shot—one of the first photographic images of lightning, taken in 1882—to launch a study of painted versus photographed depictions of the weather phenomenon.

According to Live Science’s Laura Geggel, doctoral student Alexandra Farkas first shared Jennings’ story with colleagues, who noticed that his photographed lightning bolts differed from the zigzag images popularized by paintings. Intrigued, senior researcher Gábor Horváth, head of the university’s Environmental Optics Laboratory, set out to discover if the advent of photography had influenced artistic representations, perhaps spurring painters to portray lightning more accurately.

Horváth and his team used a computer image processing program to evaluate 400 photographs and 100 paintings created between 1500 and 2015. The research is published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical and Physical Sciences.

They found that the maximum number of arms, or offshooting branches generated when charged particles follow the path of least resistance across the air, for painted images was a mere 11 while photographs depicted as many as 51.

Paintings that depicted branches tended to include between two and four offshoots, Horváth tells Geggel. Real lightning bolts, as represented by the photographs, usually split into two to 10 branches.

Horváth further notes that painted representations of lightning bolts have grown more accurate since 2000, possibly due to the widespread accessibility of online photographs.

“Painters may illustrate lightnings most frequently in their studio from memory, rather than in the open air immediately after their observation of a lightning during a thunderstorm,” the study states. “This could be one of the reasons for the difference between certain morphological characteristics of painted and real lightnings. Painters may illustrate lightnings nowadays from captured photos in addition to memory immediately or well after the event.”

In order to find an explanation for humans’ tendency to underestimate lightning’s splintering branches, researchers asked 10 individuals to look at a series of 180 images flashed across a computer screen. When asked to guess the number of branches present, participants could only provide accurate measures up to 11 offshooting arms. “These findings explain why artists usually illustrate lightnings with branches not larger than 11,” the researchers write in the study.

The New York Times’ Steph Yin reports that previous research suggests humans can assess numbers below five without counting. Six through ten require counting, while numbers higher than 10 are estimated with decreasing accuracy. Horváth says this logic may partially account for artists’ omission of branches, but he adds that the misconceived vision of a zigzag lightning bolt dates back to ancient Greek and Roman depictions of the god Zeus, or Jupiter. At this point, the image is ingrained in cultural imagination.

Horváth’s study raises questions regarding artistic representation: Should inaccurate paintings of lightning be condemned for their departure from reality? As Jennifer Tucker, a history professor at Wesleyan University, tells Yin, meteorologists once lauded the rise of photography and accused landscape artists of “spreading false rumors.”

Whereas painting is a subjective medium colored by the artist’s perceptions, the camera is an ostensibly objective tool free to make definitive claims to reality. Still, as theorist Roland Barthes noted in Camera Lucida, photography, too, is susceptible to manipulation. The camera, as he concludes, “can lie as to the meaning of the thing, being by nature tendentious, never as to its existence.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)