Why a Simple Message—Fat Is Bad—Is Failing

Extra pounds are extra years off your life, we hear. But the science isn’t so sure about that

Image: Svenstorm

It’s a common mantra: in order to live a long healthy life, you must eat well and exercise. Extra pounds are extra years off your life, we hear. Your annoying aunt might believe this with her heart and soul. But the science isn’t so sure.

Today in Nature, reporter Virginia Hughes explained that there’s a lot of research suggesting that being overweight doesn’t always mean you life a shorter life. This is what many call the obesity paradox. Hughes explains:

Being overweight increases a person’s risk of diabetes, heart disease, cancer and many other chronic illnesses. But these studies suggest that for some people — particularly those who are middle-aged or older, or already sick — a bit of extra weight is not particularly harmful, and may even be helpful. (Being so overweight as to be classed obese, however, is almost always associated with poor health outcomes.)

This paradox makes public health campaigns far trickier. If the truth was at one extreme or the other—that being overweight either was or was not good for you—it would be easy. But having a complicated set of risks and rewards doesn’t make for a good poster. And public health experts really do want most people to lose weight and not put on extra pounds.

This is where researchers, public health policymakers and campaigners are starting to butt heads. A simple message—that fat is bad—is easier to communicate. But the science just isn’t that simple.

When a researcher from the CDC put out a study that suggested that excess weight actually extended life, public health advocates fired back, organizing lectures and symposia to take down the study. Katherine Flegal, the lead researcher on that study, says she was surprised by just how loud the outcry was. “Particularly initially, there were a lot of misunderstandings and confusion about our findings, and trying to clear those up was time-consuming and somewhat difficult,” she told Hughes. But the study was a meta-review, a look at a large group of studies that investigated weight and mortality. The research is there, Flegals says, and it suggests that weight isn’t necessarily the worst thing for you. And for Flegal, what public health people do with her work isn’t really that important to her. “I work for a federal statistical agency,” she told Hughes. “Our job is not to make policy, it’s to provide accurate information to guide policy-makers and other people who are interested in these topics.” Her data, she says, are “not intended to have a message”.

And the fight against fat hasn’t really ever been particularly effective. Not a single obesity drug or diet plan has been proven to last over a year, says Hughes in a blog. And much of our weight comes down to genes, she writes:

Friedman sees things quite differently, as he eloquently explained in a 2003 commentary in Science. Each of us, he argues, has a different genetic predisposition to obesity, shaped over thousands of years of evolution by a changing and unpredictable food supply. In modern times, most people don’t have to deal with that nutritional uncertainty; we have access to as much food as we want and we take advantage of it. In this context, some individuals’ genetic make-up causes them to put on weight — perhaps because of a leptin insensitivity, say, or some other biological mechanism.

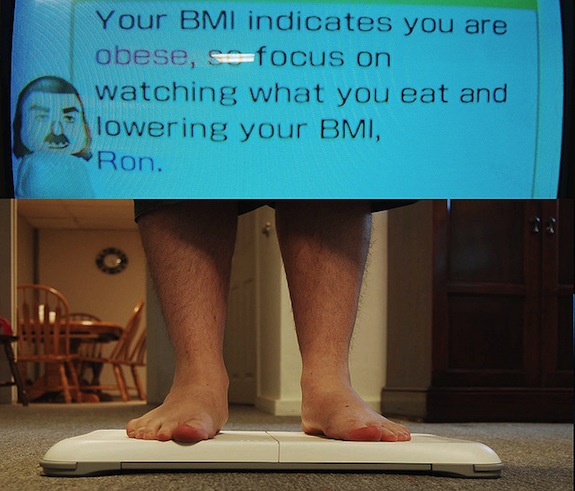

So those who are the most prone to obesity might have the least ability to do anything about it. We’re not particularly good at understanding obesity and weight yet. Some of the key metrics that we use to study weight aren’t particularly good. Body Mass Index has long been criticized as a mechanism for understanding health. Dr. Jen Gunter blogged about Flegals’s study when it came out (she was critical of it) and explained why BMI might be the wrong tool to use to look at mortality:

BMI just looks at weight, not the proportion of weight that is muscle mass vs. fatty tissue. Many people with a normal BMI have very little muscle mass and thus are carrying around excess fat and are less healthy than their BMI suggests. There are better metrics to look at mortality risk for people who have a BMI in the 18.5-34.9 range, such as waist circumference, resting heart rate, fasting glucose, leptin levels, and even DXA scans (just to name a few). The problem is that not all these measurement tools are practical on a large-scale.

And while researchers argue over whether weight really does guarantee a shorter life and policy advocates try to figure out what to advocate, the weight loss industry rakes in billions of dollars every year playing to our fears and uncertainties.

More from Smithsonian.com:

The Culture of Obesity

Taking Childhood Obesity to Task

Mild Obesity May Not Be So Bad

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rose-Eveleth-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rose-Eveleth-240.jpg)