Behold the Beauty of Disappearing Glacier Ice Caves on Mt. Hood

Catch them before they’re gone — these tunnels and caverns may soon melt away

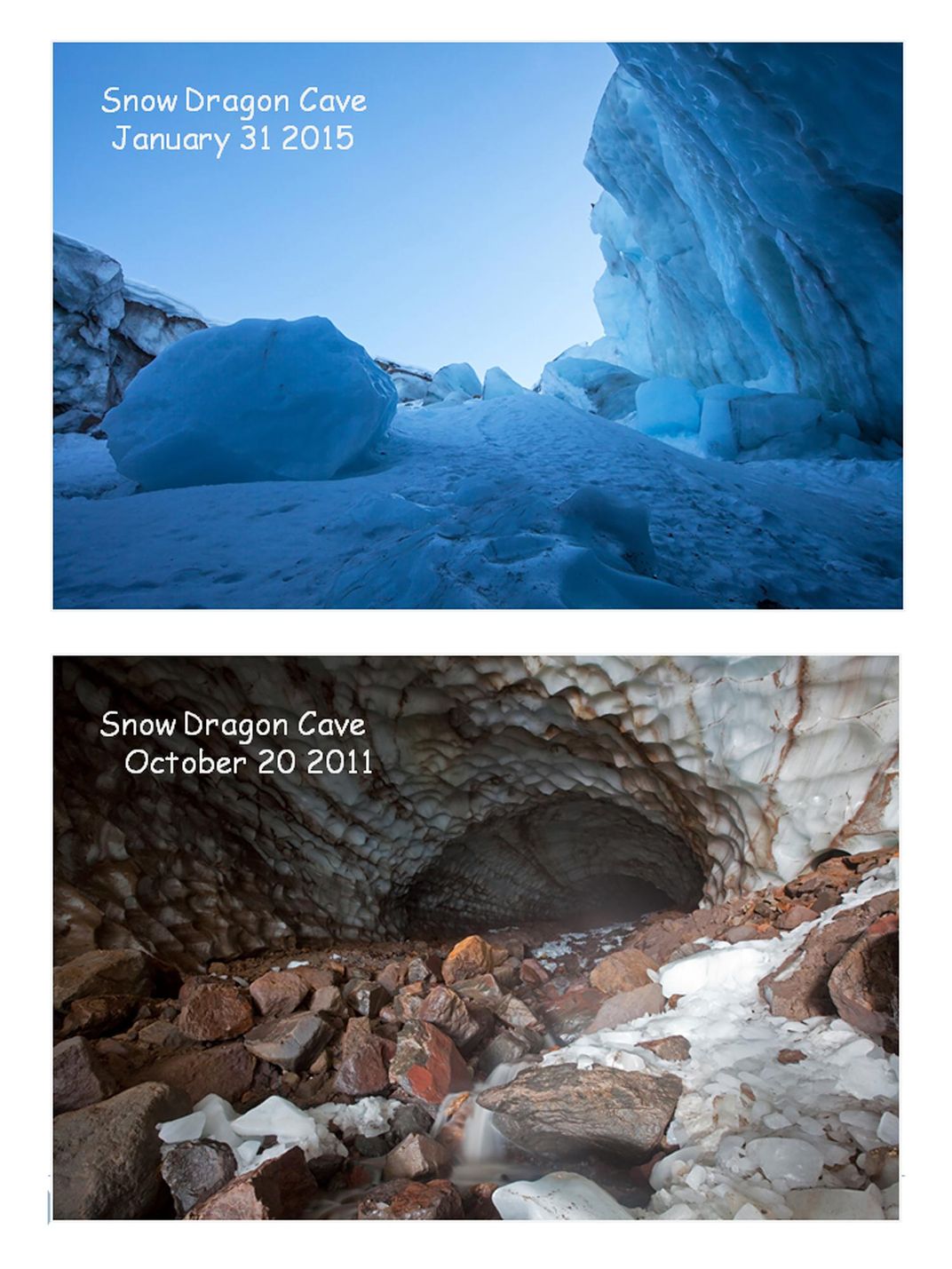

Imagine a world of ice that is as dangerous as it is ephemeral. Blue walls line the entrance scalloped by warm winds. Frozen waterfalls pour through shafts called moulins.

So goes a typical stroll through the massive cave system that riddles Mount Hood's Sandy Glacier in Oregon. But as the climate changes, the ice thins; collapse threatens. The race to document the majestic phenomenon is on.

Explorer, photographer and wood worker Brent McGregor started mountaineering in his 40s, when most people retire from climbing, he tells Sierra Pickington for the magazine 1859. He grew determined to find glacier caves and spent years scouring Oregon’s glaciers for these strange, alluring structures.

In 2011, a tip led him and several fellow explorers to the Sandy Glacier. McGregor was the first to enter the cave, dubbed Snow Dragon, rappelling in through a crevasse. He tells Pickington:

After walking along the narrow ice floor for seventy-five feet, it suddenly opened up into a giant room measuring 80 feet across by 40 feet tall, a giant borehole heading up the mountain under 100-plus feet of ice into total darkness.

Over the past few years, McGregor and his expedition partner Eddy Cartaya have led research teams to the caves, documenting the changes and naming the branches and features—Pure Imagination, Frozen Minotaur, Mouse Maze and Foggy Furtherance.

They've mapped more than 7,000 feet of passages, making it the largest glacier cave system in the lower 48 states. "The scope of these caves was too massive to keep secret," writes Cartaya writes in the fall 2013 issue of Beneath the Forest.

Small caves are normal in glaciers—as necessary as arteries—because they drain seasonal melt water. But large systems are rare enough that experts are still studying what causes them.

The Sandy Glacier's caves probably come from slightly warm air moving up the mountain, hollowing out the snow and ice. Their impressiveness is in part because the glacier is melting away. Cracks and gaps in the ice created by longer, warmer summers let increasing amounts of warm air in.

Most glaciologists can only collect data from the surfaces of glaciers but the caves give access to their underbelly. Cartaya explains in Beneath the Forest that rocks, seeds, pollen and even birds fell on the surface of the Sandy Glacier many years ago and were entombed in ice.

As the glacier melts, it releases these treasures. The team found fir seedlings growing in the cave that might be nearly 150 years old and the feathers from a duck frozen under a third of a mile of ice.

Only a handful of people are managing similar expeditions in the U.S. "You have to have all the caving skills to negotiate the caves, [and] you have to have the mountaineering skills to get there," glaciologist Jason Gulley tells Oregon Public Broadcasting.

The team made their most recent trip in October. They plan on going back, but McGregor says experts predict the cave system could be gone in five to ten years.

"We just shake our heads every time we go up," McGregor tells Smithsonian.com. "It’s like I’m photographing a new cave each time."

Ogle more photographs of the Sandy Glacier caves and follow the team's expeditions on Instagram and Facebook.