Hundreds of Holocaust Testimonies Translated, Digitized for the First Time

The Wiener Holocaust Library plans to upload its entire collection of survivor accounts by the end of the year

:focal(1028x672:1029x673)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d7/08/d7082f2f-3af6-41dc-ae76-aa93300ae321/jews_occupied_europe_1940s.jpg)

On Wednesday, people around the world marked International Holocaust Remembrance Day—the anniversary of the January 27, 1945, liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration and extermination camp.

Due to pandemic restrictions, survivors and educational groups couldn’t visit the sites of Nazi atrocities as they have in years past. But a new digital resource from the Wiener Holocaust Library in London offered an alternative for those hoping to honor the genocide’s victims while maintaining social distancing. As the library announced earlier this month, hundreds of its survivor testimonies are now available online—and in English—for the first time.

The archive, titled Testifying to the Truth: Eyewitness to the Holocaust, currently includes 380 accounts. The rest of the 1,185 testimonies will go online later this year.

“We must not turn away from the hardest truths about the Holocaust, or about the world in which the Holocaust happened,” said Toby Simpson, the library’s director, during a recent virtual commemoration, per the Jewish News’ Beatrice Sayers.

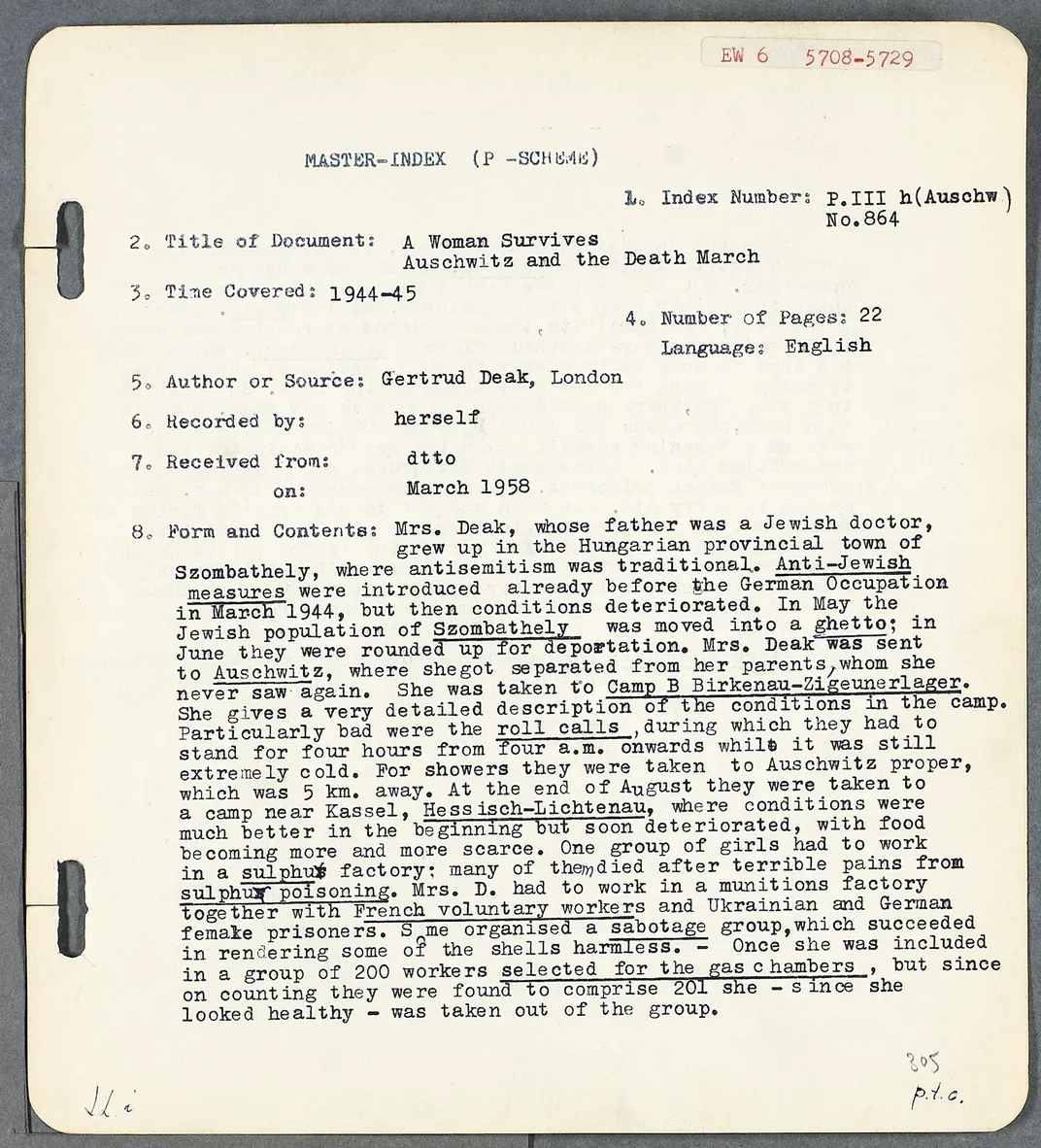

Among those who spoke to the library’s researchers in the years after World War II was Gertrude Deak, a Jewish woman from Hungary who was interned in multiple concentration camps, including Auschwitz-Birkenau. In her testimony, Deak outlined details of life in the camps, including brutal physical labor and going without food or anything to drink.

At one point, she recalled how two women escaped from the camp but were recaptured by the SS.

“We had to stand and watch, while the two girls dug their own graves, then were shot,” Deak said, “and we had to bury them.”

On another occasion, Deak was one of 200 workers selected for the gas chambers. Upon recounting the group’s numbers, camp guards realized they’d accidentally included 201 individuals. Because she looked healthy, they took Deak out of the group and let her live.

Toward the end of the war, Deak was forced to walk barefoot through the snow on a death march. When she was unable to keep going, her captors left her lying in the road. She received help from several German women, who fed her and let her hide in a barn, where she was eventually found by Russian soldiers.

Other accounts tell of resistance to the Nazis, both inside and outside the camps. In one, Austrian police officer Heinz Mayer describes joining the illegal organization Free Austria after Germany annexed his country. Mayer’s father was killed at Auschwitz, and Mayer himself was arrested, tortured and eventually sent to Buchenwald. There, he was assigned to work in the post room, which was the center of resistance at the camp.

“It was the easiest place for smuggling post to the outside world and for exchanging news,” Mayer explained in his account.

When American troops arrived to liberate the camp on April 11, 1945, prisoners armed with smuggled weapons stormed the watchtowers.

“As the Americans were approaching, the SS thought that it was them who were firing the shots,” Mayer said. “The SS fled, and the prisoners armed themselves with the abandoned weapons. We occupied all the watchtowers and blocked the forest in the direction of Weimar in order to intercept any returning SS.”

When Mayer gave his account in 1958, he reported that many of his companions from Buchenwald had already succumbed to the consequences of their time at the camp. He’d been deemed “unfit to work” due to a lung disease he contracted there.

The London library is named after Alfred Wiener, who campaigned against Nazism and gathered evidence documenting the persecution of Jews in 1920s and ’30s Germany. In 1933, Wiener fled the country with his family, settling first in the Netherlands and later in the United Kingdom. He continued his work while abroad, gathering materials that ultimately formed the basis for the library, according to the Telegraph’s Michael Berkowitz.

As Brigit Katz reported for Smithsonian magazine in 2019, Eva Reichmann, the library’s head of research, put out a call to Holocaust survivors in 1954, asking for help documenting their experiences.

“Under no circumstances must this material, written or unwritten, get lost,” she wrote. “[I]t has to be preserved for the future historian.”

Over the next seven years, trained interviewers—many of whom were Holocaust survivors themselves—spoke with eyewitnesses, taking notes and summarizing their stories in the documents that have now been digitized.

The library has previously used its collection of testimonies in exhibitions, like one last year that told the stories of resistance work by European Jews. As Claire Bugos wrote for Smithsonian in August 2020, the show helped fight the persistent myth that those targeted by Nazis were passive victims. Another exhibition at the library documented the impact of the Holocaust on Roma and Sinti people.

In addition to the testimonies, the online archive includes letters, scholarly reports and other materials. Visitors can search through the documents by subject, date range and name.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)