Tate Britain Confronts the Aftershocks of World War I

The museum’s newest exhibition explores how British, German and French artists struggle to comprehend bloody conflict

The scenes presented in Tate Britain’s newest exhibition, Aftermath: Art in the Wake of World War One, range from mechanically detached— American-British sculptor Jacob Epstein’s “The Rock Drill,” a futuristic merging of man and machine echoing the cold brutality of modern warfare—to uncomfortably vulnerable—in German Expressionist Otto Dix’s “Prostitute and Disabled War Veteran. Two Victims of Capitalism,” the economic exploitation of human flesh is rendered tangible.

“Aftermath,” which opened this week and runs through September 23, traces the resonance of the so-called Great War through more than 150 British, German and French works dating between 1916 and 1932. According to a press release, the show’s intent is to explore the war’s impact on artistic style and choice of subject, as well as art’s overarching role in memorializing and understanding conflict.

The exhibition is organized largely in chronologic order, according to TheArtsDesk.com’s Katherine Waters. This allows viewers to trace artists’ evolving treatment of war in conjunction with the historical development of key artistic movements. As Waters notes, the assemblage-like logic and free-flowing ideas of the room dedicated to Dada collages and Surrealist paintings, for instance, suggest that “in a world of broken images,” representation can only be rendered in fragmentary terms.

Some of the earliest works in the exhibition, such as British landscape painter Christopher Nevinson’s “Ypres After the First Bombardment,” finished in 1916, but likely begun in February 1915, veer toward abstraction, juxtaposing the angularity of half-destroyed buildings with amorphous smoke clouds. Others are more direct, forcing viewers to confront the post-traumatic stress experienced by veterans: As The Guardian’s Maev Kennedy notes, Berlin Dadaists John Heartfield and George Grosz’ “The Middle-Class Philistine Heartfield Gone Wild,” constructed in 1920 depicts a doctored tailor’s dummy with a lightbulb in place of its head, a reference to the electric shock therapy prescribed for shell-shocked soldiers.

Another sculpture of note, German artist Wilhelm Lehmbruck’s “The Fallen Man,” exudes defeat in stark comparison with Epstein’s powerful “Rock Drill.” Its subject, which The Guardian’s Adrian Searle describes as “stalled in a position of extreme vulnerability and abjection in his attempt to crawl off somewhere,” mirrors the despair of its creator, who committed suicide in 1919.

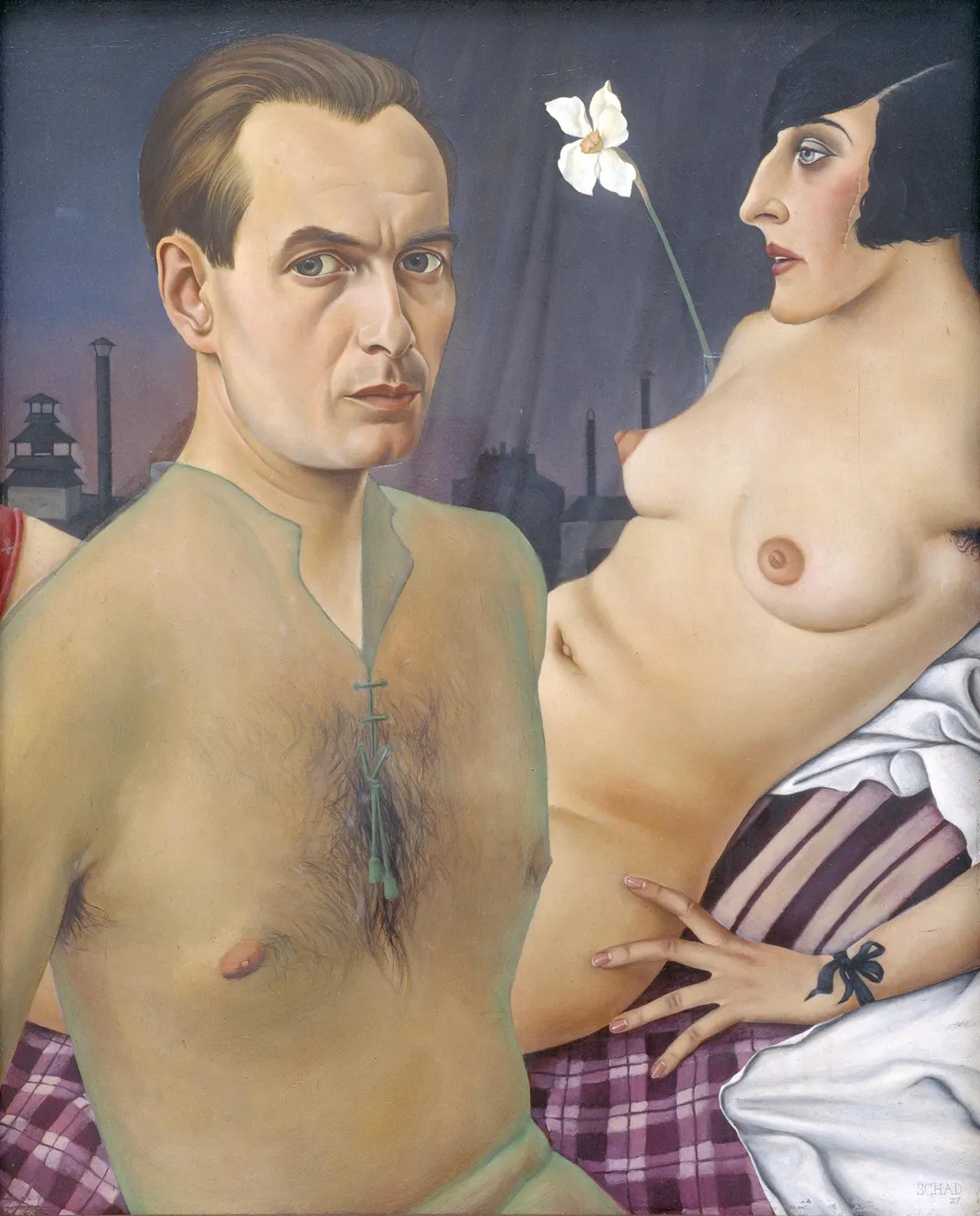

The Telegraph’s Alastair Sooke notes that during the 1920s, many artists turned from avant-garde abstraction, which was perhaps too indicative of the "fractured forms" engendered by war, to realism. Still, these later interwar pieces bear the marks of conflict. In German painter Christian Schad’s "Self-Portrait," a nude woman reclines behind the artist, her body seemingly unmarred by wartime scars. Closer examination of the woman’s face, however, reveals a small scar. Like Dix’s prostitute and veteran, she, too, has been marked by the societal forces around her.

What is perhaps most striking about Tate’s exhibition is the art’s modern-day resonance. As Alex Farquharson, director of Tate Britain, tells The Guardian’s Kennedy, “There are injuries, physical and mental, first experienced in the first modern war which are still common on battlefields today, particularly Afghanistan.”

"Aftermath: Art in the Wake of World War One" will be on display at Tate Britain until September 23, 2018.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c8/e2/c8e26c96-df2b-4d1e-934c-0441494d97d8/jacob_epstein_-_torso_in_metal_from_the_rock_drill_1913-14.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/75/74756e93-471f-4ba8-87f3-79d88292dd2b/otto_dix_-_prostitute_and_disabled_war_veteran_two_victims_of_capitalism_1923.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)