Scientists ‘Digitally Unwrap’ Ancient Egyptian Animal Mummies

Detailed scanning technology provides a detailed look at a kitten, cobra and bird

:focal(982x624:983x625)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/26/50263bce-d220-4055-a484-911905670aac/50247913621_0bdcdda733_h.jpg)

For some 2,000 years, a collection of mummified animals have been preserved, with details about their life and death hidden under layers of muslin. Now, researchers have found a way to digitally peel back the layers and “dissect” the animal underneath using a high resolution scanner.

Researchers studied three animals—a cat, a bird and a snake—in a seven-year collaborative project by Swansea University’s College of Engineering and the University’s Egypt Centre.

The team used a detailed scanning process called micro-computerized tomography (CT) to better understand how the animals were mummified, conditions in which they were kept, possible causes of death and the handling damage mummies sustained. The findings were published yesterday in the journal Scientific Reports.

“This paper pushed resolution and analysis to its limits, revealing more than could be determined through lower-resolution methods or even through real-life unwrapping,” Richard Johnston of Swansea University, who led the research, tells Matt Simon for Wired. “New understanding can contribute to building the picture of life at that time, while the specimens remain undamaged.”

Studying teeth in the cat’s jawbone which had not yet come through suggests it was a kitten of less than five months old. Based on the separation of its vertebrae, researchers think it may have been strangled and its neck snapped.

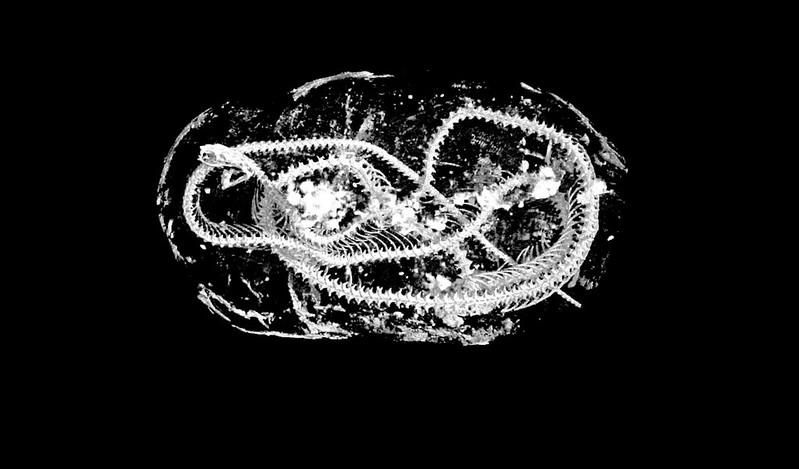

Researchers identified the snake to be an Egyptian cobra. It suffered bone fractures across its vertebrae and on its skull, meaning it was probably killed using a whipping motion. The microCT scan also revealed that its kidneys were calcified to a degree that suggests the snake was kept in poor condition when alive, likely with little water.

It also appears that the snake was part of a complex ritual that involved placing small amounts of myrrh or natron—a sodium carbonate that was used for ancient embalming—in its open mouth before mummifying it. The practice is known to have been used for humans, and the researchers say that if similar deposits are found in other species, it could mean there was a similar process for mummifying animals, according to the paper.

Based on bone measurements, researchers concluded the bird was a Eurasian kestrel. These were the most commonly mummified raptors. Because of the large number of mummified birds that have been discovered, the researchers think many were collected from the wild.

The mummification of animals was a common ritualistic practice in ancient Egypt. Archaeologists have discovered cats, ibis, hawks, snakes, crocodiles, dogs and numerous other mummified animals which were considered divine. Some of these are buried in tombs with their owners and are believed to be offerings to provide a food supply for the afterlife, according to the Neil Prior for the BBC.

The researchers describe an established mummification “industry,” with high production volumes and significant infrastructure to breed or capture animals for mummification and sale. Temple priests embalmed the animals, and visitors to temples could purchase them as an offering to the gods. Perhaps as many as 70 million animal mummies were created this way.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/87/fd/87fdbaa5-5b1d-4eb2-ba6a-515ef3b212dc/50247917806_b6a5e0e960_c.jpg)

The machine researchers used to get beneath the mummies’ layers of muslin wrapping and understand the structure of the animals can create 3-D images with 100 times the resolution of medical CT scans.

The micro-CT takes thousands of individual X-rays from all angles while the mummy rotates 360 degrees. Unlike medical CT machines which move around the stationary human, the object of study in a micro-CT scan is placed on a platform between the stationary X-ray source and the camera, where it can be rotated and repositioned. The resulting image can be viewed from all angles.

"With the micro-CT software we can create a virtual reality image of the scan as large as a house, if you like; I can actually walk around inside the body of the cat and make microscopic measurements to examine in minute detail," Johnston tells the BBC.

Based on the detailed final images, the team created a 3-D printed replica of the cat’s skull at twice the actual size, allowing them to physically examine it without damaging the mummy, reports Wired.

Johnston, a professor of material science, says the collaborative project began over a cup of coffee with his colleagues in the University’s Egypt Centre. He suggested the school of engineering’s X-ray machine might be used to better study mummies.

"Up until then we'd been using the technology to scan jet engine parts, composites, or insects, but what we found when we started looking at the mummified animals was extraordinary," he tells the BBC.

In a statement, Carolyn Graves-Brown of the Egypt Centre, says the collaboration between engineers, archaeologists, biologists, and Egyptologists shows "the value of researchers from different subjects working together."

This technology could open new opportunities to scan mummies that are otherwise little-understood. In November 2019, Egypt excavated the tomb of a royal priest and discovered dozens of mummified sacred animals including cats, crocodiles and lion cubs dating back to the seventh century B.C., according to Jack Guy for CNN.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_1578_copy_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_1578_copy_copy.jpg)